2023 looks like a digital version of 1923 because of growing poverty, homelessness and an eternal cost of living crisis.

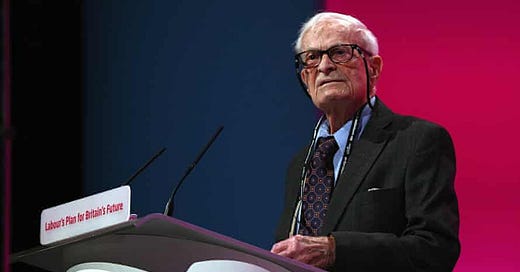

Five years ago, today, Harry Leslie Smith began his dying in earnest. But instead of lingering on his ending this Sunday, I am concentrating on his beginnings and the journey he and his generation took to build a society where everyone mattered not just the entitled few. Sadly, their great achievement-The Welfare State was dismantled by the most well off in society because the top 10% of income earners believe a dignified life is for them exclusively.

The Green and Pleasant Land was unfinished at the time of my dad’s death. I've been piecing it together from all the written notes, typescript & index cards. The fifth anniversary of Harry Leslie Smith's death is November 28th, I hope to have the first 50k words of this work ready for you to read shortly, and will post as many chapters as I can before the end of the month. Each chapter will be free to read for the first two days and then revert to paid subscriptions only.

Gentle Reader:

I am eighty-seven years old. My death approaches with actuary punctuality. I have lived a long life. Perhaps, too long because my body is wearied from decades of existence. The party is almost over for me. My journey across time was a wonderful adventure. I had an abundance of experiences. I intimately knew hunger, poverty, sickness, and grief as I was born into the working class before the Welfare State was created.

But I was also on first-name terms with love, comradeship, and the delights of having a family. I will go from this world as I came with nothing. But with this book and any other book I may write in the future, if I am permitted a handful more years, I leave behind my footprint in the sands of history.

.

Chapter One:

I was born on February 25, 1923. I am told the winter of my birth was harsh and that the night my Mum went into labour with me, a fierce rain slashed against my parent’s rented domicile, located in a slum on the outskirts of Barnsley. We were poor folk because we were working class. Had I been given a choice; I would not have picked either the era or the economic circumstances into which I was born. But none of us chooses to whom and where we are born.

It was a fearful, unstable, and melancholic time to come into existence. Grief over the dead from the First Great War was still as sharp as broken glass because the end of that conflict was just five years old. A hundred million were slaughtered in that war. They died for nothing except the vanity of the monarchs who ruled Europe in that era and the greed of their munition makers. World War One’s start and ending dissolved empires into revolutions that first brought hope and then tyranny. No revolution came to Britain after the war. That wasn’t because it didn’t need one. It was because we were still a mighty empire, and the entitled who ruled over us kept the ordinary worker in a firm yoke of patriotism and poverty.

The working class was on the back foot in 1923 because if the war hadn’t made them aware of the brevity of their existence, the plague known as the Spanish Flu that came after the 1918 armistice certainly did. The virus was a modern-day Black Death, and it collected the living and put them in their graves with medieval haste. It brought death everywhere in the world, including Yorkshire, and then in 1922; it petered out like a forest fire that burnt down all the trees.

It is little wonder why my mother was in labour with me for hours. I just didn’t want to budge from my safe harbour inside her womb and meet a world full of threats, harm, and caution. I would not be coaxed out with either gentle words or harsh curses. But I eventually did come into the world in the early morning hours. I let all around me know I wasn’t pleased by hollering at the top of my lungs after a midwife who loved gin and shag cigarettes slapped my arse. I mewled like a runt of the litter for milk from my Mum’s breast because I was underweight. Being born malnourished was normal for my class in 1923. My dad earned his grub as a miner, and like all workers then, no matter how hard they laboured never had enough money to pay the rent and feed their families. We were capitalism’s beasts of burden and treated accordingly.

Working at the coal face is what my folk have done since our time began. It’s all they knew, which is why even before the Industrial Revolution, my folk were miners, except then it wasn’t coal we dug but tin. I am sure, in ancient times, my ancestors dug for the metals that were smelted into bronze. For generations, my family’s labourers and the millions like us made the entitled wealthy and us their humble servants. Had my working-class world not been changed by the Great Depression, I too would have kept hearth and home by hacking coal in its rich seams of Yorkshire like all my kind through our recorded history.

In the year of my birth, my parents were new settlers to Barnsley. They had come to this spot of Yorkshire because the pits here promised a better wage than up in Wakefield or Barley Hole; and Barnsley was far enough away from my dad’s siblings, who despised my mother.

When I was older, and Mum was soured by the hunger created by the Great Depression, she revealed to me my father’s family were a little bit more than colliers. They were “better folk” according to her. My- dad, she said in her moments of acrimony during the 1930s, had let a family pub slip through his hands. “It could have kept us in clover until we all breathed our last.”

On the day of my birth, my father was not glad-handed down at his local by neighbours in our village of Hoyland Common. No one slapped his back or shook his hand in congratulations because; when I was born, Dad was in his late fifties, and Mum was 27 years his junior. She had foolishly fallen in love with him in 1913. He had the gift of the gab and an optimism that was infectious. My mother attached her wagon to my Dad's destiny ten years before my birth because she believed, despite his advanced age; he could guarantee her a secure future. Mum lived until the day of her death feeling cursed by the creed: marry in haste and repent in leisure.

But no one else she knew had Dad’s prospects. His father was the innkeeper of a public house that stood on the fringe of a colliery in the decrepit village of Barley Hole, located in the nether regions between Sheffield and Barnsley. So, when my granddad died in 1914, my parents assumed my father would become master of the New Inn and his days as a coal miner would be over. My parents married on that expectation. But my parents’ dreams for financial stability were as hopeful as believing a sandcastle would stand after the eventide comes ashore. Life always has other plans for us rather than happiness and a pocket full of cash.

My father didn’t inherit the publican license after Granddad died. Instead, it transferred over to his uncle Larrat ensuring Dad would die a miner rather than a business owner. The machinations Larrat employed to accomplish this were as pernicious and preposterous as any subplot from a Dicken’s novel or at least that is how it seemed to me when my mother during the 1930s ranted about our “lost legacy.”

After my grandad died my parents moved on from Barley Hole with few possessions except a portrait of granddad and an upright piano that was once played by Dad to entertain off-shift miners with seaside songs from Blackpool.

According to Mum, bad luck followed our family with the persistence of a stray dog looking for an owner because of Dad’s tender heart. He wasn’t “rough and ready,” even after decades at the coal face. Poor Dad, was the toughest of us all because he took the misfortunes to come in the years after my birth with stoicism and good humour. But none of his family recognised it because we were too busy trying to escape our own destruction.

Nine years had passed since the time of my parent’s marriage to my wails of life. The intervening time was a series of disappointments and defeats for my parents. Their relationship in 1923 was shorn of its lustre. Mum was only twenty-eight, but she felt like a broad mare when I was born having already given birth to my two elder sisters, Marion in 1915 and Alberta in 1920. Whereas Dad was fifty-six and his physical strength was in decline. His ability to earn a living and us out of the poor house was in jeopardy.

The worry, the daily struggle to stretch Dad’s impecunious wages to both make the rent and put food on the table had by the time of my birth worn my mother down to a nub of anger, outrage and cunning that she hoped would outwit whatever calamity was intent on knocking on our front door demanding entry. Mum’s acerbic vigilance was understandable because besides having to battle the rent collector for arrears, she also battled the grim reaper who waited with impatience for my sister to die from spinal tuberculosis. By the time of my birth, Marion was gravely ill from it. TB terrified my mother because her older brother Eddie died from it in 1918 after doing a stint in the Veterinary Corps in France. Mum knew what awaited Marion, but my mother would do everything to forestall my sister’s early reservation with death. But a mother's love for her child isn't a currency that can be exchanged for proper healthcare in a society designed to make profit for the few.

This month marks the 5th anniversary of my dad's death. It also marks the second anniversary of my Harry's Last Stand newsletter going live. During these past 24 months, I have posted 245 essays, as well as excerpts from the unpublished works of Harry Leslie Smith - along with chapter samples from my book about him. My newsletter has grown from a handful of subscribers to 1200 in that period. Around 10% of you are paid members. I appreciate all of you but ask if you can switch to a paid subscription because your help is NEEDED to keep me housed and Harry Leslie Smith's legacy relevant. But if you can't all is good too because we are sharing the same boat. Take care, John.

Boy - this man could write.

Thank you so very much for sharing.