2024 will be as desperate as 1932 for those crushed between the jaws of a worsening cost of living crisis & governments beholden to the 1%.

Hi Everyone:

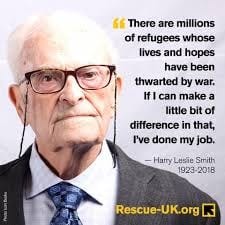

Below is a selection from Chapter 16 from Harry Leslie Smith’s The Green And Pleasant Land.

Baring rapid worsening of my lung disease, a return of my cancer or homelessness I will have finished all the edits and piecing together of my dad's unfinished work by May. 35k words of the 80k word manuscript is now complete. It’s been a long haul because I have other projects that I must do to try to keep the lights on and to be quite honest am knackered. But who isn’t in these shit times that we live in? . But I am pleased I have voyaged this far with the manuscript.

Chapter Sixteen:

It was late in the winter of 1932 when my family moved from the doss house on St Andrew's Villa to an outbuilding in the nether region of Sowerby Bridge. We left Bradford as we had come to the city in 1928 with little more than the shirts on our backs.

My sister and I knew what awaited us in Sowerby Bridge was the same poverty and feeling of hopelessness we endured in Bradford. But we were children and had no choice- when it came to our mother's necessity to rely upon her boyfriend, Bill, who promised to keep us fed.

On the day we departed, my sister argued with my mother outside the front steps of the doss house. Alberta wanted to say farewell to our estranged father, who now resided in a room in one of the doss houses across the street from us. My mother said there was no time, and no point to it because I suspect she hadn't informed my dad of our leaving the city.

When we left the street that had been my neighbourhood for two years, a sense of shame overcame me. I knew we were leaving my dad behind for good. We weren't ever going to return for him. He was going to have to make his way alone in this slum as if he were a stranger to us. .

After a bus deposited us at Sowerby Bridge, my mother informed us that our new lodgings were at the top of a steep- and winding road far from the town's high street.

The long walk to our new residence seemed more like a march because my mother barked at my sister and me to get a move on and stop dawdling. Both my sister and i carried sacks that contained the few possessions we owned, while my mother held onto Matt as he was only two years old. The further we moved up the steep hill, the more the housing on each side of the road began to resemble the slum dwellings built near the coal mines that surrounded Barnsley, where I spent my first years of life when my father was employed in the pits.

Atop the hill was a crossroad where we turned right and proceeded to a farmhouse. At first, I thought this was our new lodgings but was quickly informed that this was where our landlord lived. Our new home was an outbuilding located off- to the side of the farmhouse.

The building was smaller than a one- up-one-down tenement but larger- than the room my mother and Bill let at St Andrew's Villas. At one time, the outbuilding was used to house farm labourers. It must have been a hard and miserable existence for them. Later on, I learned one of the farm workers housed in that outbuilding in the 1920s hung himself on an exposed beam that jutted, like a railway trestle across the the ceiling of the kitchen.

It was dark inside the outbuilding owing to a lack of windows and gaslighting. The walls were damp and the cement floor was brittle with cold. A long, narrow stone stair, covered in cobwebs, led upwards to the bedroom, I shared with my sister. As there was a perpetual draft inside the building, the candle I used to guide me to bed at night generally blew out before I reached my bed which was a filthy mattress that rested on the floor as if it were disposed already in a tip.

My mother and Bill took the parlour because it had a coal fire grate to keep them warm. The view from the narrow window upstairs bedroom was a barren field that contained a few craggy trees bent against a grey sky that dripped down cold, wet rain.

The slums that my family had lived in previously had been dismal places. But at least they were in urban settings, where I could find comfort in the company of other children who were just as poor as my family. Living here- in this outbuilding- on a hill atop Sowerby Bridge- I was totally isolated. More importantly, my mother was also alone. She was totally dependent on Bill for food and support. She soon learned Bill withdrew both affection and material support with the capriciousness of a dictator because his character was malicious and violent.

Thanks for reading and supporting my substack. At this time of the month it is always a bit of an SOS with the rent. I really need your help and need 20 new subscribers to keep me under a roof. Your subscriptions to this newsletter do that. They also help keep my housed which has become a precarious thing- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities as I age in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John

That has been the goal for sometime now.

The oligarchs are determined to anything / including another mass slaughter akin to WWII to get all of the power back that they lost, and maintain it.

It will take incredible sacrifice to stop them once and for all.

I hope you’re wrong. But economists say we have not understood the delay factor on interest rates alone. The government sold their soul for money and votes, screeed over the young and kept them down. In Canada real estate is an absurd part of our economy, the %. I’m sure there are other reasons. The manufacturing base is gone due to tech innovation and globalization. The service jobs that replaced them are horrible. Not close to living wage. .