The whole purpose of my Substack is to use my life, my father’s, my family and my ancestors as a working-class history of Things Past. Not necessarily Proustian but an ever-evolving document. A testament to the worth, uniqueness and profoundness of the lives of ordinary people who are continuously erased from history. It's why the entitled own our present reality because we have been taught by them our existence is unimportant except as consumers of their mass-produced goods of ephemeral value. Below is some more from my book about my life with my dad during the last ten years of his life

Chapter Twenty-four:

I Stood with Harry

Hey Dad,

The seasons are changing again, and autumn now approaches on cat’s paws. The light in the evening sky grows less, and although the sun is still warm to the touch, there is a bite in the morning air. Soon the birds will fly south, and the leaves will change colour. By the time my fifty-eighth birthday arrives in late October, frost will cover the ground in early morning. Our hemisphere is slipping into winter, like humans fall into old age without even knowing it.

On many occasions, I didn’t expect to live this long and thought my body would pack it in or I would take my own life, after counting my bad days versus my good ones. But it didn’t happen. Mum too, when she became unwell with Rheumatoid arthritis, wanted to commit suicide if things became too much. But you convinced her to remain alive, as you convinced Peter when psychosis almost drowned his sanity. And for the last decade of your life, you were kept alive by me because that is what we did as family, albeit imperfectly, stand together.

I will also remain alive by channelling the brute stubbornness in my DNA. Through days of feast or famine, my ancestors survived. And that is what I will do. I still believe I have a chance to find more instances of that elusive joy, we humans seek as much as bodily nourishment. It has come to me before, perhaps not in the abundance of others, but it hasn’t been absent in my life. So, I will continue to reach out for it despite it being mostly a fruit that hangs too high in a tree for me to reach.

Physically and emotionally, I know I am stronger than when I set out on this journey through cancer and covid. The clamour that once persisted in my ear from breakfast until bedtime that cried, you will soon be no more, is now a whisper.

I realise that what remains of my voyage through life will be difficult. From now until the end of my time, I will always live under some shade of grief. But the foliage is no longer as heavy as a jungle's canopy, so light does shine down, and hope exists.

Politics however is less hopeful, because covid should have produced a new social contract between governments and their citizens. But it didn’t. No new social welfare state will be forged from the suffering produced by this pandemic in every nation across the world. Too many simply didn’t ask for it, as your generation did in 1945.

Instead, as the perceived threat of the pandemic diminished, the multitudes clamoured for a return to happy hour specials, pop up shopping extravaganzas, no money down furniture, all-inclusive holidays and 24/7 sports entertainment.

People want a return to normal to be the right to be diverted from the adversity of their lives through bread and circuses. No one will take to the streets in western countries to demand real change to their existence.

So, for me, I must decide what normal I want to return to?

For me, normal hasn’t existed for decades. It’s for certain that after Peter died, nothing was normal for me or you. We entered another stage of our existence that didn’t have the certainty of the past or the ordinariness of anonymity. It was a period of extremely arduous work and perseverance that provided us with a different reality that if not normal was at least the safest harbour we could find. It was a path to walk free of our grief and leave a reminder of our time on this earth. But I am still trying to process if what we did, what I did was worth the cost.

********

Following the 2016 Referendum, we spent the summer working on your last book. I hated that we didn’t have enough money for a proper holiday. Instead, I took you on picnics or to the lakeshore near our apartment, so you could enjoy the summer sun. However, neither the book nor the season allowed us to escape the news about the growing humanitarian crisis, the war in Syria, had created. For over a year, refugees were fleeing in their thousands to Europe, Turkey or any nation that would accept them. The war in Syria produced a refugee crisis worse than the one which erupted during the dying days of World War Two, when millions of European refugees took to the roads to flee armies clashing over the blood lands of Europe. “At least then,” you said, “People after suffering so much themselves in a merciless war wanted to be generous with the peace.” Now, they don’t give a shit because they don't understand the heartache wars produce.”

The longer you lived, the more your early past seemed to repeat itself. “Intolerance, narcissism, and greed, will be written at the entrance to the tomb of the early decades of the 21st century.” You were becoming increasingly impatient with politicians, and the news media's indifference to poverty, racism, economic and inequality. “The suffering of the ordinary is just a collection of buzz words to get well off people elected to parliament.” You were pissed off and started to feel that nothing we had done since Peter died had altered anything for either good or bad.

In the Autumn of 2016, we decided it might make a difference if you travelled to Europe’s refugee camps and broke bread with the displaced people of the world who were being ostracised by Europe, the USA, the UK, Australia, and Canada.

On your first trip to a refugee camp since the 1940s, we took the Euro train to Calais to meet refugees who lived in a sprawling unregulated camp dubbed the “Jungle,” by its inhabitants. On the train, we felt ashamed as we ate a breakfast of fresh croissants and excellent coffee, knowing that the refugees we were about to meet were underfed. A taxi took us from the Euro Star station in Calais to an underpass at the entrance to the refugee encampment. Seeing it, you said, “this is worse than the chaos in 1945.”

It was a desolate, horrible place made more unwelcoming by a November rain that spit from an angry dark sky. I feared for your health there because you were easily chilled. On every trip, I always had visions of you taking sick and dying, and then feeling responsible for it.

Volunteer aid workers met us at one of the entrances to the camp. When you crossed into the camp, you whispered to me “abandon all hopes, all ye who enter here.” It was a dismal strip of industrial land on the outskirts of Calais. It was densely packed with over nine thousand inhabitants from the Mideast, Africa, and Afghanistan, all ill-equipped to withstand the harsh winter approaching. The residents slept in donated tents, burned refuse for warmth, and lived in such unhygienic conditions that diseases like TB were rampant. But you still didn’t decline the hospitality of some Afghans when they brewed a cup of chai boiled in condensed milk. I remember feeling as you listened intently to their stories about escaping from their country, both pride in what you were doing and concern because they were openly coughing, and I was worried about some communicable disease spreading to you.

It was hard to push you through the camp in your transport wheelchair because the pathways were rutted by rain as well as the trod of thousands of feet. At one point, a group of refugees offered to lift you aloft in your chair to better understand the horrors they lived in. We declined, but for our day there, I couldn’t get an image of you and your wheelchair hoisted on the shoulders of refugees, as if you were a battered image of a saint being carried by supplicants in a church procession.

The Jungle didn’t feel like the refugee camps you had visited as a young man at the end of the war when you were stationed with your RAF unit in Hamburg. Then you said, refugees knew that to be in an allied displacement camp signalled that the horrors they had endured during the war were almost over. Now though, most refugees rot in substandard camps in developing nations or on the fringes of Europe.

After we left, we felt sick knowing that few of those people in the Jungle were going to be allowed to find sanctuary. They were simply going to be perpetually on the run or deported back to their own countries where they’d die from politics, theocracy, or economics. Anyway, we looked at it; those people had drawn the short straw in a corrupt world ruled by the entitled.

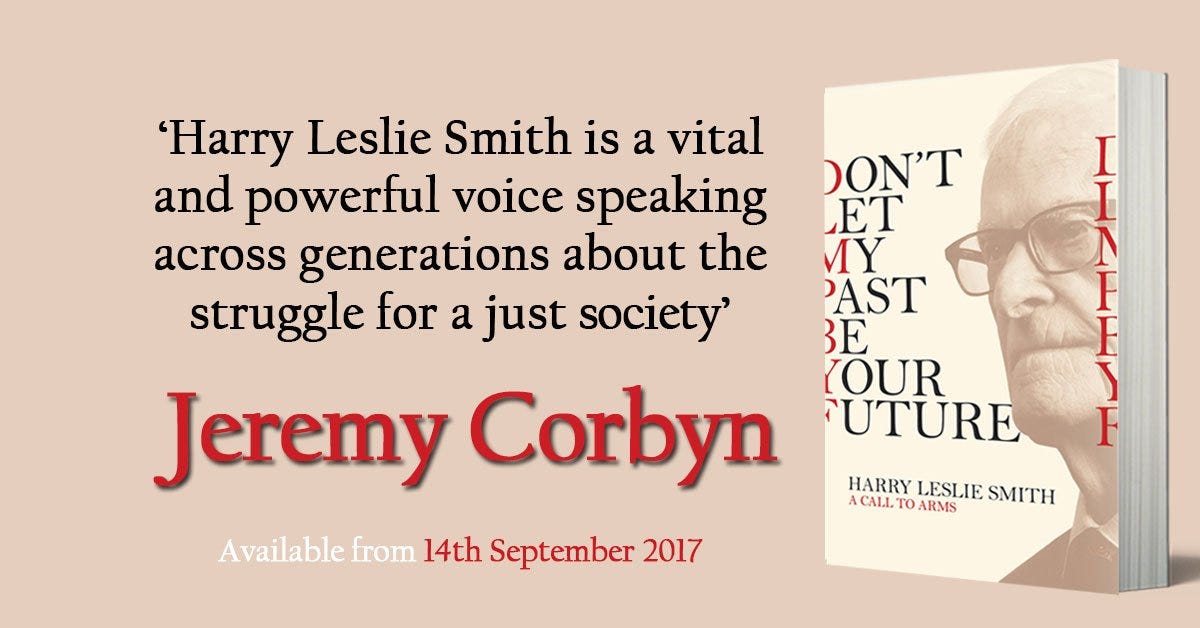

Upon your return from Calais, you met with Jeremy Corbyn in his parliamentary office and told him what you saw there. It appalled you and him that the desperate of the world were treated with less respect than recyclable rubbish. From your trip to Calais until your death two years later, the plight of refugees tormented you. In them, you recognized all the mistakes and sins of Neoliberalism come home to roost. Moreover, because modern society is now governed by dog-whistle politics, you surmised refugees were going to die in their thousands trying to reach safety and receive no accommodation or sanctuary for their efforts. Your last book attempted to create the reasons for building a more compassionate society, which included making refugees welcome.

However, the bloom had gone off your brand due to your ardent support for Jeremy Corbyn. The media class we depended on to promote your life and experiences was losing interest in you because unlike so many other influencers, you refused to denounce Jeremy. You had so many opportunities to join the crowd who wanted to destroy Corbyn’s leadership. Owen Smith was so desperate to get you to support his leadership bid, he left many obsequious voice mails, on our telephone where he called you “mate.”

“That, arsehole, is no mate of mine.”

Were it not for your social media presence the last eighteen months of your life would have been like when we started this odyssey in 2010, because you had much to say but few avenues to be heard.

That autumn, we prepared for what would be your last book tour. I sensed you didn’t want to go. You were weary. But you went because you felt you owed me, your publisher, your fans, the dead, one final push for a better Britain. I promised you it would be your last tour. No one would ever put you on the road again, and I would find a way for you to have a garden to putter in when the next summer returned.

The tour was short, and you worked as you had always done with a relentless passion. I was worried everyone pushed you too hard, including me. I wasn’t happy with how the publisher constructed the tour or the outsourced publicists, with whom I was in a continuous argument over overwhelming, redundant, events that didn't fit your politics. The publicist wanted you to do Piers Morgan on GMB. "It will sell books."

But I told them, “My father doesn’t do interviews with dickheads.”

The tour was too much for you. Your body was simply too old to be put in the yoke or as you called it, "the bloody shuck." to flog a book. I felt guilty and stressed and regretted the whole trip from the moment we arrived.

Halfway through it, you came down with an infected eardrum. At a dinner with your former editor, you complained about a sudden pain in your ear, but then brushed it off as nothing. The next morning you awoke, and your pillow looked like the last pillow Abe Lincoln rested on because it was soaked in blood. I didn’t feel good about any of this. I had a private doctor come to the hotel room and treat you because I didn’t want you waiting in an NHS A&E for hours. You somehow finished the tour, but I felt guilty and ashamed that I hadn’t provided better for you, so you didn’t have to do this arduous travelling.

When we left England and landed at Pearson, in Toronto, I was relieved. Once again you had beat the devil and stayed alive.

But by Christmas, you were in the hospital with pneumonia which from that point onwards, you never shook.

Most of January 2018, you spent in hospital. I still thought you were going to fully recover because your doctors told me so. “He’s tough, he can pull through.” But by February, you were in for a short stay in hospital again.

Each time you were released from the hospital, I took you home. I would tell you, now you are retired. You can recover and enjoy the time you have in the sun. I fed you, bathed you, pampered you as much as possible. It didn’t matter though because you developed congestive heart failure. Now you needed a walker to amble about the apartment. You shuffled and had become your chronical age, you were an old man, and your memory grew confused or faded. When you were well enough, I’d take you out for drives or trips to the store. Without talking about it, we knew the final darkness of death was beginning to set. The long shadow of your ending was now cast over our daily life together. Sometimes when you were in the shower, I heard you sing the lyrics to Kurt Weil’s September song, “where days dwindle down to a precious few, but there's a long, long way between May and September.”

Often, I would find you asleep on your chair with your notes scattered on the floor.

Your macular degeneration was now in an advanced stage which meant you couldn’t recognize faces on television, read a book or a newspaper. “That’s okay, I can still recognise you are my son.” Like Milton’s child, I read to you so that you knew what was going on in the world. You needed adult diapers at night because pneumonia had weakened you so much, you weren’t aware of urinary urges.

Many nights you called out to me, “I am a fucking baby, I’ve pissed the bed again” when the diapers leaked through. I’d calm you, clean you up, change the sheets, and get you back to sleep. It’s funny right after my operation, and for the first few months, I routinely soiled the bed and reflected considering it’s the same mattress from when you were alive; “it’s going to ask for danger pay.”

Your legs needed constant care from a nurse because your skin was beginning to break down. A fingernail brushing lightly against your hand could cut you as if it were a knife.

I lived in the moment, striving to be a caregiver and not think too far in the future. I believed I could keep you going for a few more years. I wanted to keep you going. And then one morning, life had other plans for us.

I’d gone to fetch your medicine from the pharmacy. Outside of a Shopper’s Drug Mart, a dog attacked me and threw me off balance and onto the pavement. The fall broke my arm and taking care of you became much more complicated.

By the end of that August, you had developed a persistent UTI. There was not enough home-care support, and with my broken arm, I couldn’t clean you properly. You began to despair, and deep down I guess you thought you had become a burden. You sank swiftly throughout the autumn and suffered from delirium on many occasions. You didn’t remember Peter’s birthday in September and forgot mum’s as well. It broke my heart that you remembered mine and were so apologetic that you weren’t well enough to buy me a card. You didn’t sleep, and when you did, you were troubled by bad dreams. I was utterly exhausted and broken. But I carried on, although sometimes I wondered if there was a sharpness in my voice towards you?

Due to your infection that no antibiotic could contain, you began to sundown like a dementia patient. Once, I came into your bedroom and you asked if mum had made my breakfast before I went to school? On another occasion, I caught you with a suitcase. When I asked you what you were doing, you replied, “we are late for our flight to Portugal.”

You were dying before me, and I would have done anything to stop that from happening. But I couldn’t because you were old and didn’t have much fight left in you, and I didn’t have any fight left in me because I was knackered.

You fought death one last valiant time during your final stay in hospital. But you couldn’t raise your shield to protect your body from its mortal blow. So, you died and left me alone….

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. A yearly subscriptions will cover much of next month’s rent. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John.

i love the sheer reality of your writing.

Excellent, but so sad