Beneath the Surface: A Working-Class Childhood in 1930s Britain

Make no mistake under Keir Starmer's Labour Govt-the past will become today.

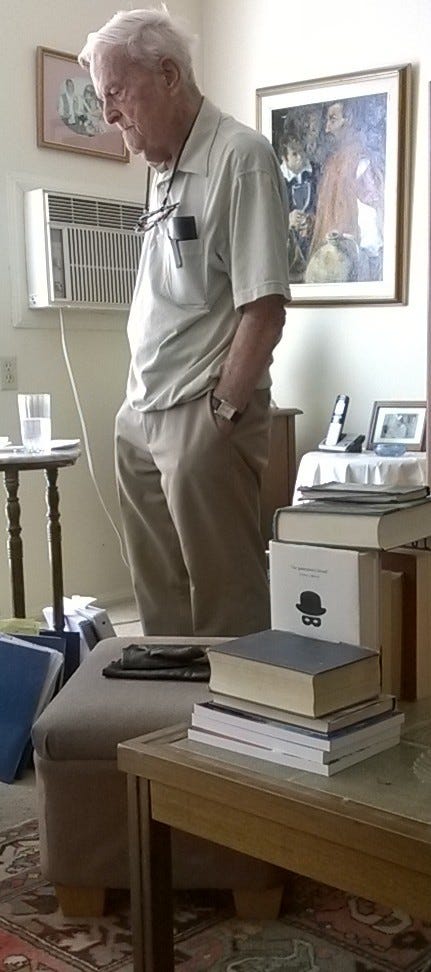

I’ve lived with my dad’s unfinished work, The Green & Pleasant Land, for the past 18 months. It’s now complete, aside from a few minor edits. Letting it go will be hard, because this story has lived in my head since I was seven — when my father first began telling me bedtime stories about his youth. For better or worse, those tales shaped my character and the man I became.

Rent day is tomorrow, and the scramble for the last bit continues. So below is another excerpt from Harry’s final work — his last words on the poverty that scarred his generation’s youth.

I’ve included a tip jar because it helps with rent and keeps a candle burning for The Harry’s Last Stand Project.

Chapter 20

From the age of seven, the adults in my life made it clear I had to “pay my way.” Bill, however, was even more blunt. When we arrived in King Cross from Sowerby Bridge,

"Lad, when I was in the navy, lazy sods were tossed overboard."

I got the message and began looking for work the day after we arrived. A few miles from our new lodgings, a Jubb’s outlet had a “Help Wanted” sign in its front window for a delivery boy.

Inside, the manager asked if I could ride a bike and handle heavy lifting. When I said yes, he hired me immediately.

It was arduous work. I loaded groceries into a woven basket mounted atop the bike’s front tire—often weighed down with 60 pounds of goods. Most work days I pedalled a 20-mile route across Halifax and the rural areas surrounding King Cross.

I did my duties energetically and without complaint. I was an eleven-year-old boy who wanted to be known as a "good worker." Such was the condition of my class—even in the 1930s—we saw ourselves only through the lens of usefulness to capitalism.

On an emotional level, I understood my servitude was unjust and it angered me that I was invisible to middle-class children. It was also humiliating they didn't see me as anything more than part of the scenery to make their lives less burdensome. To them, I existed as their workhorse. Their inherited wealth, their fathers’ wages, and grammar school upbringing indoctrinated them into a belief system where they were the masters and the working class their servants.

I despised them. I also envied the leisure hours they enjoyed whilst I strained to ride my overloaded delivery bike. As I huffed and puffed, sweated and groaned from transporting my cargo, I caught glimpses of middle-class kids on their way to attend birthday parties, music lessons, or the matinee.

Sometimes, these middle-class kids tossed me the same awkward and uncomfortable glance one might give an animal burdened with cargo. But I was still not intellectually aware that child labour and enslavement to work through poor wages were things that could be eradicated if ordinary people became militant.

After a few months at Jubb’s, the manager expanded my duties to include working behind the counter. He liked keeping me at the front of the store because he was having an affair with one of the married female clerks and spent much time with her in the back storeroom.

I caught them having sex on the sugar sacks once too often. But instead of firing me, the manager gave me the task of designing the store’s window display.

I became so adept that one of my displays took second place in a community-wide competition.

I began smoking at the age of 11 because my manager said it would give me more energy and stop me feeling hungry. Every week, I bought Woodbine cigarettes for two pennies a packet of five fags.

At break time, I stood outside, placed a fag on my lips, and struck a match. The coarse tobacco soaked into my callow lungs, made my head dizzy, but quieted my hunger pangs.

Next door to Jubb’s was a high-end chocolate shop. Their chocolates were all hand-crafted and presented in rich, beautiful boxes far out of reach of an ordinary worker. The store’s clientele was mainly affluent housewives, with their well-dressed children in tow. They were ignorant or indifferent to the poverty around them. They certainly perceived me as a non-entity if they saw me washing down the stoop at Jubb’s.

With a reputation for excellence, the shop routinely discarded entire boxes of chocolates deemed unsatisfactory. These were dumped in a bin behind the store they shared with Jubb’s.

Out back, in the rubbish bin, exquisite boxes of chocolate wrapped with bows and ribbons lay like buried treasure amidst rotting produce. It seemed too good to waste, and many times at the end of my shift, I dove into the rubbish bin to fish out a box. The top layers were usually mouldy, but the chocolates beneath were perfectly edible. The looted boxes I brought home to share with my sister, mother, brother Matt, and Bill.

We were gobsmacked by the richness of their taste and how the middle class lived so much better than our bread-and-dripping working-class existence. A box of those chocolates, if bought in the shop instead of fished from the bin, was the equivalent of a week's rent for us.

We needed that treat, considering much of the time Bill Moxon’s butcher shop was empty of customers. Moxon lacked the temperament and capital to be a shop owner. Without clients, he passed the time standing outside, kicking a pig’s bladder filled with water like a football until it burst.

If it weren't for shady dealings in stolen beef, Bill’s shop would have shuttered within the first month. However, it continued for half a year until closed due to rent arrears. He was the only one surprised by its failure. Moxon was a man of no self-awareness because the news that my mother was pregnant with his child took him by surprise.

Mum’s pregnancy didn’t sit well with Bill — he was outraged by any form of familial responsibility.

Out of money and schemes, Bill buggered off. One morning, after a night at the pub, he said to Mum,

"I’m better off without thee."

When my mother pleaded with him to stay for the sake of the child growing inside her, he denied paternity and called her a whore for becoming pregnant.

After his outburst, Moxon got up and left.

That morning, Mum looked as shell-shocked as she had in past moments when Moxon hit her for speaking out of turn.

Mum didn’t know what to do without Bill — since 1930, she had viewed him as a life raft. She’d abandoned our father because she believed Bill promised survival for her and us during economic calamity. Mum had damned herself and us by the extreme measures she took to be with Bill.

My sister and I turned our backs on our father to facilitate Mum’s relationship with Bill—a deed that forever stained us with guilt.

Mum had given everything to be with Bill and was now ostracised by her family.

For years, she’d taken his beatings because he offered a meagre salary that paid the rent on shambolic, sub-human housing. Mum was so unimportant to him that he abandoned her, pregnant and without income.

With Bill gone, Mum warned us,

"There’s nowt in the cupboard. There’s nowt left but the workhouse for thee — if I don’t fix this."

My mother’s warnings terrified me. My sister was less anxious because she was already working full-time in a mill. It did not pay much—she was only 14—but Alberta knew she could afford a room somewhere. Alberta tried to assure me that in time, we’d come through poverty safe. I wasn’t convinced. Fear of the workhouse made me resent Mum; I blamed her for leaving us vulnerable. I was too young to understand that working-class women had few options surviving in a harsh capitalist world dominated by men.

Without Bill, Mum sought refuge—and courage—in drink. At the time, I thought her trips to the pub were acts of cowardice and escapism. I believed she was wasting what little money we had on selfish pleasure, and I openly attacked her for it.

Later, I learned her trips were desperate attempts to keep us together and housed. Occasionally, Mum sold herself for rent to men looking for sex — not uncommon for working-class women in the 1930s.

Many times, my sister and I hauled our mother from between bins outside our home after she came home blind drunk from the pub. We dragged her indoors, hoping no neighbour had seen her fall or witnessed us carrying her, drunk and lifeless. Mum would sleep it off and wake bitterly angry with herself for scraping rock bottom.

In January 1935, a few weeks before her pregnancy was due, Mum told us she was leaving King Cross.

"I will find Bill and fetch him back to us."

She left for Bradford with money scrounged from my piggy bank, which she busted open with a butter knife, overcome by desperation.

"You’ll be right as rain—because you can make more of it."

She took our baby brother Matt with her and left him with her sister Alice, the only sibling who still talked to her.

Thank you for reading and supporting my SubStack.

Your support helps keep me housed and allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith.

Rent day looms like the high beams of an oncoming truck. Your help — through tips, subscriptions, restacks, or even a few words of encouragement — keeps this work alive and me standing.

As I write this, I’m $115 CAD short of covering next month’s rent, with just hours to go.

If you can, a paid subscription — £3.50/month or £30/year — would mean a lot. I’m currently offering 20% off yearly subscriptions.

There’s also a tip jar for one-time support.

Living with cancer and lung disease makes everything harder — especially during this cost-of-living crisis. Every bit of support goes a long way.

📚 A Legacy Nearly Complete

Over the past 18 months, I’ve worked to complete my dad’s Green and Pleasant Land — the unfinished story of his generation’s youth, which Harry left behind.

The manuscript is now done, save for a few edits. It traces his life from 1923 to July 1945, ending with Labour’s landslide victory.

I don’t know who will raise all boats in the 21st century — it certainly won’t be Labour in Britain, the Democrats in the U.S., or the Liberals in Canada. The West has entered its Last Orders phase. The fight for a better future will be as bitter as it was in the 1930s and 1940s.

War is coming home to us, soon.

Take care,

John