Leaving the RAF: March 1948

From “The Green and Pleasant Land” by Harry Leslie Smith

At the time of his death, my father was working on The Green and Pleasant Land, a multi volume memoir that aimed to give a ground-level view of working-class life in Britain. He wanted to capture how the hardships of his early life—so deeply affected by unfettered capitalism—were ultimately mitigated by the creation of the welfare state and the promise of socialism. Through his story, he sought to preserve the memory of a generation that fought for dignity, fairness, and opportunity, and to remind us that the entitled and the neoliberal political system will never willingly give the ordinary people a life worth living. We must take it.

Chapter Five:

It was the second week of March 1948 when I was demobbed from the RAF. They didn’t mind me leaving, since I had paid back the £50 bounty I’d taken six months earlier when I re-enlisted for five years, hoping it would prolong my posting in Germany. It didn’t because they didn’t appreciate the lower ranks being married to citizens of former enemy nations.

At Ringway, it was a formality to leave because they had plenty of new recruits to take my place for less pay.

So, it was a meeting with my commanding officer, who sat behind a fastidiously arranged desk. Its surface was clean of any clutter except for two telephones and a small photo of the officer’s family in a silver frame. On his neat desk, there was also a thin folder that contained my service record, a list of my postings, my training in wireless operation, and my performance ratings with the RAF since my induction in 1941.

I saluted him and a warrant officer who was also present. I was instructed to be seated. My commanding officer started to make notes on a sheaf of paper. For a second, I thought they had forgotten that I was present or that I even existed.

I focused on the large portrait behind the adjutant officer’s desk. George VI looked stern but fatherly, and I thought:

“Well, Your Highness, you’d best not have any complaints about me — I’ve done enough for you and your family.”

My imaginary dialogue with the monarch vanished as soon as the adjutant officer cleared his throat and said:

“Didn’t you, in September of last year, sign on with the RAF for three more years of service? Now you want to leave?”

Yes.

“You don’t know whether you are coming or going, Smith.”

“Well, we won’t keep you if you don’t want to be kept. Your record,” he said, touching the file on his desk, “rates you as a superior Air Crew man. There are no stains in your copy book, so I am not going to put up a fuss.”

“Thank you,” I responded with a grin.

“I’d hold off on that grin because I think you shall remember us fondly once you get back onto Civvy Street.”

“Perhaps. But might I ask when that will happen?”

“We should be able to clear you out of here on the day of your six-month anniversary, March sixteenth.”

The officer looked at the NCO, then to me.

“Is there a problem in sorting this out in forty-eight hours? Is L.A.C. Smith doing anything especially important for the nation while in your care, sergeant?”

“No, nothing important, sir,” said the sergeant.

“Well then, let’s get this done and on the double. We don’t want to waste a farthing with excess personnel.”

The officer looked at me and continued.

“This new government, the one that your lot voted in…” he said with a sneer.

“You mean Prime Minister Attlee?” I asked.

“Yes. The Labour government is hell bent on bankrupting and destroying the Royal Air Force, the Royal Navy, and the Army. So fly the coop, L.A.C. Smith, and good luck to you because you shall need it in this New Britain your people created.”

At this point, a gloomy silence settled over the room, like the moment when a coffin is lowered into a freshly dug grave. With a final, measured salute, I pushed back my chair and stood, bracing myself for the mundane tasks that awaited outside the office.

I left his office and made my way back to the parade square to gather my squad and dismantle radio equipment for one final day.

It is all over now.

I was elated, yet also despondent. So much had happened to the world, to Britain, and to me since I enlisted in the RAF in 1941. I had grown up and matured in both body and mind while civilisation clashed on battlefields strewn across the world.

It occurred to me that, since my induction into the RAF, I had saluted hundreds of NCOs and officers from sunrise to sunset. I had saluted sergeants during squad bashing, at the end of forced marches, and after live ammunition training exercises. I had saluted officers both on parade and after a tongue-lashing for misbehaviour. After seven years of service to the King, I had saluted superiors across the British Isles, through Belgium and Holland, and finally in occupied Germany.

During my RAF stint, I had brought my right hand to the brim of my cap and down to the side of my trousers over ten thousand times. Most of those salutes were made with a flourish, but with little belief or conviction. They were much like the motions I employed during communion as a small boy: the sign of the cross or the salute was done as a ritual to demonstrate obedience to an unseen, cruel god or government and evade the wrath of priests or sergeants.

Yet, unlike the church, the RAF had been an honourable tribe to belong to. I was proud to have been a respected member and done my duty.

In many ways, I felt better prepared for this uncertain peace because of my apprenticeship with the RAF. I entered the Air Force as a callow and naïve individual, but I left with a destiny to finally pursue. I didn’t crave fame or wealth. I just wanted what had been denied my kith and kin in Yorkshire for generations: love, financial stability, and purpose. With a Labour government and a promise of socialism in our time, I was prepared to fight and defend my right to live in a world fit for the working class.

On my final day, I didn’t take long to pack up my belongings. I was asked to report to the paymaster to receive any money owed to me by the RAF. I was handed a couple of pounds and coppers and placed them in my wallet. My finances sorted, I was then ordered to the supply hut to begin my transformation into a civilian again.

In the cold supply hut, a clerk ordered me to strip to my underpants. I stood shivering while a pimply lad noted in a ledger each item of returned clothing.

“You look about the normal fit, so you can have your choice of suit. We have either brown or brown.”

“I guess I’ll take the brown one then,” I said.

He handed me a thin, single-breasted suit that felt as though it had been woven from horsehair.

Clutching the stiff fabric of my new suit, I stepped out of the supply hut and trudged toward the adjutant’s office, the final stage of my demobilisation awaiting.

The clerk signed a piece of paper that said all that had been loaned to me by the state had been returned in good order. I was dispatched from there to the adjutant’s office. A sergeant whom I was not familiar with took my papers to the officer on duty. My papers were signed, and I was discharged from the RAF. Everything was done with as little emotion as if they were shipping a lorry-load of beans back to the factory, rather than discharging a human being from their service.

Contemptuously, the sergeant gave me a once-over while I stood cocksure in my brown suit, which hung loosely on my shoulders. This sergeant gave me my final order:

“Well, that’s sorted. Off you go.”

My last day at Ringway was much like my first day in the RAF at Padgate: I was alone, with only strangers for company. I had one last cigarette inside the compound at Ringway. As I walked to the entrance, the sun was breaking through the clouds.

The crisp morning air reminded me I was truly leaving, not just the RAF, but a world I had known for seven years.

At the camp gates, I showed my discharge papers and felt cold in my new kit. The guard smiled at me as he would to a lorry driver delivering milk.

“Tara,” he said, handing me back my papers.

I walked out of the enclosure with long, proud strides. Far off in the distance, I thought I heard the bark of a sergeant on the parade ground. Perhaps it was just my imagination, but I could have sworn the NCOs were ordering his squad to “eyes right.”

As I made my way down the road, the bellows of all the sergeants who had ever ordered me about followed me on the wind. The further away I walked from the camp, the fainter the voices grew, until all I heard was the sound of my own breathing.

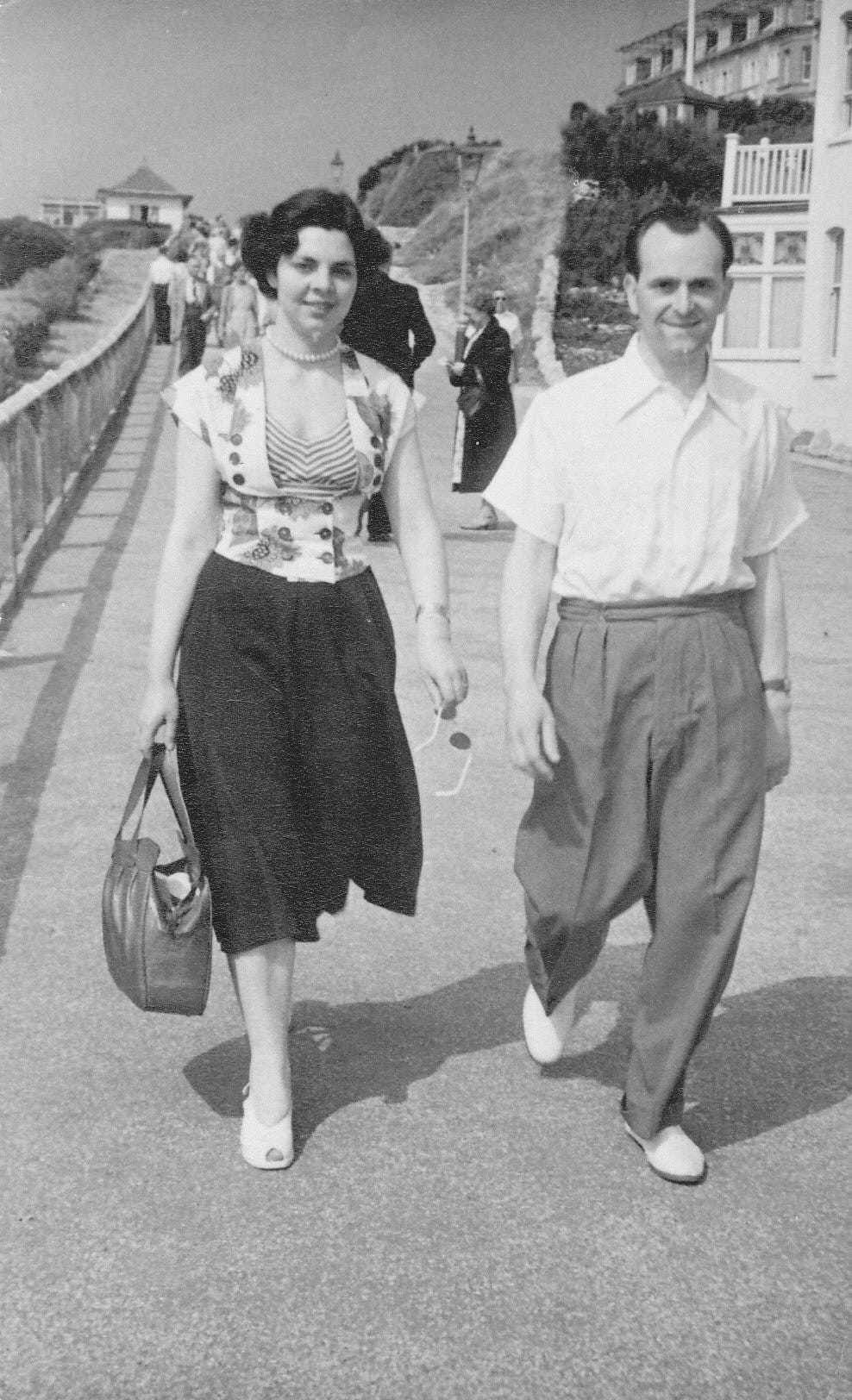

The road ahead was deserted, but I was not disappointed. I was on my way to gather Friede. My eyes were fixed, my orders clear; I was on the right path, even if it meant returning to my past, to my mother, and to her terraced house in Halifax.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. If you can, please consider a paid subscription — just £3.50 a month or £30 a year (converted to your currency). I’ve reduced the yearly price by 20% to make it easier, and a yearly subscription alone covers much of my essential expenses, including this months prescription medicines. There’s also a tip jar for anyone who feels inclined.

On brighter news: The Green & Pleasant Land, after 18 months of work, is now complete in beta format and will go to a publisher this month. My father’s story, and that of his working-class generation, must be remembered if we are to resist today’s fascists. If you’d like a beta e-copy, let me know. Take care, John