The Green & Pleasant Land tells a true story about the lives of working-class people who lived during a time of political and economic catastrophe during the decade leading up to WW2. It’s my Dad’s story about his past but the tale is universal because a life of entitlement is for the few and one of misery or desperation for the many. It’s why the Greatest Generation built the Welfare State following the defeat of Hitler to prevent a return of fascism by ensuring everyone shared in society’s prosperity.

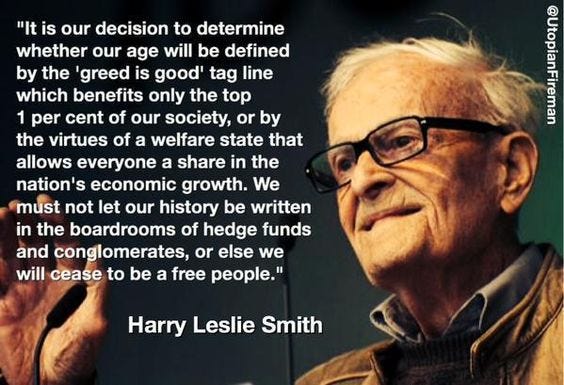

The Harry’s Last Stand project, which I worked on with my Dad for the last 10 years of his life- was an attempt to use his story as a template to effect change. It was his final battle to remind people not to make his past their future.

His unpublished history- The Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project. I have been working on it, refining it, and editing it to meet my dad’s wishes. It’s almost done. Below is another chapter excerpt about his experiences of growing into manhood during an age when fascism was on the rise.

The Green & Pleasant Land:

Chapter Twenty-five

After Alberta left our house on Boothtown Road, I moved into her bedroom in the attic. The room was damp, cramped, unheated, and the roof leaked.

But, for the first time, I felt liberated to not be required to share a flock mattress with another family member as if we were barn animals in a pen.

That cubby hole of a room gave me a privacy I never before enjoyed, in all of the other houses my family lodged in when we were on the run from debts or to find work in a land emaciated by mass unemployment.

As I worked long hours at Grosvenor's, I wasn't home much, and that pleased me no end because our house was rife with harsh and vocal acrimony.

When I was there, outside of meals, I retreated to my attic lair to escape the raucous screaming from my mother, Bill, or my younger brothers.

I preferred to spend my spare time at the library attempting to improve my education.

I also went to many lecture series at the Mechanics Institute in Bradford. There, I attended talks from British volunteers returning from the Spanish Civil War front. These men spoke about their experiences fighting Franco and how Hitler was preparing for war with the rest of Europe. In the working class districts where I lived people's politics were more street level trade unionism concerned only with wages and working conditions. They wanted to separate and ignore the other issues that determined the extent of our exploitation by employers, from the equation of how to obtain a fair deal for their labour.

At the end of each talk, a hat was passed around to assist the war effort or provide aid to Spanish refugees. During those evening lectures, I began to learn the words to revolutionary songs like The Red Flag and The Internationale.

There was a camaraderie to those talks, I never encountered before, these evenings in Bradford. It was comforting but also strengthening because it gave me resolve to want a better future for everyone not simply myself or those I loved

I was growing enough as an individual that by 1937, I knew I wasn't a communist. But I was damn certain I was a socialist.

At home, Bill didn't appreciate my politics because although working class his allegiance was to the Tories and those who oppressed ordinary people. Moxon was barely literate but he could read a newspaper. His favourite was the Daily Mail because it contained words of hate against minorities, communists, Jewish refugees and those opposed to the British Empire. So, Bill and I clashed often and bitterly during any time I found myself with him.

1937 was also the year, l found enough moments in my day to develop friendships. Some of them were lasting and others fleeting.

Outside of the relationship I had with my sister, the most important relationships I formed during my early teens were with three lads with similar backgrounds, to mine. Like me, they wanted to forget the hunger from childhood caused by the Great Depression.

Eric Whitely was a year older than me and an apprentice engineer. Eric was all-modern, quick-witted, and boastful. But he was also a Labour Party member and believed in worker solidarity. He grew a wispy-haired moustache that- with his thin terrier face made him look like someone on the take. It was make-believe, but he cultivated that impression so that others would see him as more worldly than Halifax permitted. Eric introduced me to Roy Broadbent, who lived with his mother and elderly aunt.

Broadbent worked at Macintoshes making sweets and did so until the 1980s- never once being promoted to a different job position in his forty-eight years of employment there.

Roy- like me- lacked a father in his life. But his dad left his life through death rather than being abandoned by his family like mine had. His mother coddled him, which made him somewhat of a narcissist. By all accounts, he had a very easy Great Depression. But Roy made up for that because of the action he saw as a member of the Cold Stream Guards during the Second World War.

Eric’s father was very much alive and was a lamplighter. On my way home from work in Halifax's tea time light. I'd see Eric's father igniting the gas lamps with a large staff at the lower end of Boothtown Road, near the public baths. He'd bid me good evening and tell me to stay out of trouble.

On Saturday nights, Roy dressed copied the look of an American gangster which was popular because of American films. I was envious because I didn't have extra money for spare togs and found ways at the pub to nurse half a pint for hours. On those nights Roy wore a fedora hat and sported wing-tipped shoes.

Eric called him “boss” in mock deference. Roy's personality was the furthest thing from being a boss. Any time, Roy opened his mouth or extended his hand, he exuded a soft, kind, plodding personality. In his youth he was incapable of malice except for the sin of vanity. However, in middle age that changed because his lack of political awareness in youth made him a prime target for Thatcher's Tory propaganda.

The final element in my trinity of mates was Doug Butterworth. He lived near King Cross with his mother, brother, and sister. I loved Doug the most because of his family. His mother always let me kip at their house if I had rowed with my mother.

It was the first time in my life that I felt accepted as an equal, and these friends never judged my dodgy background. Still I didn't feel comfortable enough with them to express often my growing militant views on politics. I kept quiet about my more socialist beliefs because it felt safer to have friends than strong opinions that I didn't have the means to act upon.

After work on weekends, my friends and I would meet up in a pub and nurse a half pint until it was time to go to the cinema or the dance hall. At the pub, despite the Spanish Civil War being on all the newsreels in 1937 and something that interested me, my friends and I never discussed it. Instead, we talked about football or the girls we fancied.

After the pub, if there was no movie to our liking, we went to a dance hall where jazz musicians played swing music from America. I didn't know how to dance. There had been no time or money to learn. So when I was at the dance hall, while Roy and Eric found girls to dance with, I circled the dance floor's perimeter. If I saw a stray, partner-less girl, I'd chat them up and inquire if after the dance; they wanted company on their way home.

If I was lucky, a girl accepted my invitation. With some, we both agreed to stop on the way at People's Park. There we'd kiss or or grope each other in furtive and futile attempts at sex. There was more failure than success as I was petrified about getting my partner pregnant. I had witnessed, too many times, love wrung out of adults from the cruelties of trying to keep themselves and their kids fed in times of economic catastrophe.

I was always fearful Alberta would find herself pregnant. During her early teenage years and after she moved out, my sister was trying to escape the despair of our house by finding affection from a young boy her age and sometimes older ones. She spent more time attempting to protect me than herself.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John.

A great story, I always want to read more!

I often wonder what historians will write 100 years from now.

Your father could not have imagined consecutive world wars and the spread of Western democracies.

I can envision a myriad of medium-term climate, financial, and societal catastrophes, but I can't forsee the plot curves of the Trumpian era.

We're not returning to strong (if fallible) democracies, but there's far too much unrest for long-term authoritarian/kleptocratic rule.

What will be the black swan event of our times?