Child Labour in 2024 is as it ever was an exploitation of working-class kids. It is the same capitalism & politics normalising it today that did so in 1932.

Hi Everyone:

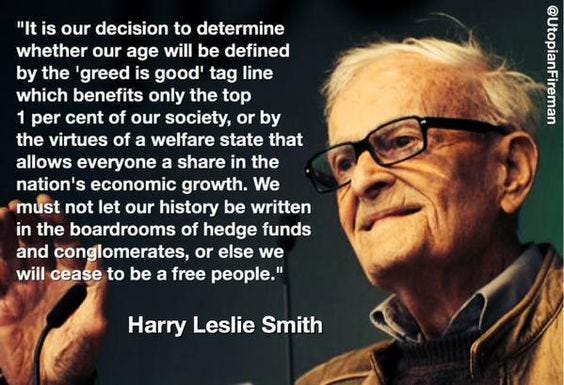

Below is a selection from Chapter 17 of Harry Leslie Smith’s The Green And Pleasant Land. My dad would have been 101 this month had he not died in 2018. I miss his company. But strangely I am glad he died when he did. Six years ago, we had a chance to pull back from the brink and choose not to go into the darkness of fascism. What we are living now will only get worse and it will take more than a generation to change. This Green and Pleasant Land Project that will be completed and ready for a publisher in May is a fantastic testament- not only to him- but every working class person from the Great Depression, who made it loud and clear after WW2- that they weren’t prepared to live short lived lives of misery to ensure the entailed maintained their wealth.

Chapter Seventeen:

I understood how to survive in the city slums of Bradford but Sowerby Bridge was a different story. My heart was desolate from living in that farmer's outbuilding in the hills above the village. When I lived there, there wasn't enough food, warmth or love to engender hope in me that everything would be all right.

There was nothing to divert me from the glumness of our Great Depression existence. Cinemas and libraries were a fair distance from our farming neighbourhood. And, the wireless was still an entertainment for richer folk.

I only had my imagination to keep myself hopeful that something better might come to my life than the day in and day out of existing on the margins. Sometimes, I told myself stories where my dad came and rescued my sister and me after he was awarded a legacy from a wealthy deceased relative. They were idle daydreams as fragile as soap bubbles that burst before me each time I remembered my father was skinter than us and lived hand to mouth in a Bradford doss house.

I viewed my new surroundings and people with distrust and uncertainty including the farmer who rented us the outbuilding. He was gruff and had a long, shaggy white beard that made him look like a biblical patriarch in suspenders. He seemed to me like all of our landlords-- someone to keep well away from.

But one day, while he worked his field- he spied Alberta and me dragging our feet in the dirt. He called us over and told us to go into his barn and jump from the rafters onto his haystacks. "It's like landing on a featherbed."

Shortly after we had settled into the outbuilding, my mother found Alberta and myself work. It was as she said to pay our way. Alberta was put to work in the kitchen of a more prosperous farmer than our current landlord. On occasion, my sister scoffed the leftover food or pudding to add to our meagre diet that still consisted too often of boiled, mashed or fried potatoes, despite Bill's promise of butchered animals from his job at the nearby rendering plant.

For me, Mum convinced a local coal delivery company to take me on. "He may look scrawny, but my lad's as tough as nails."

At first, the owner was unimpressed with my potential but he was eventually won over to hiring me from a combination of my mother's hectoring and his thrift.

A nine-year-old shifting a hundredweight coal sacks to village homeowners and the surrounding environs was cheaper than paying an adult's wage for another man to assist his one-person operation.

The owner delivered coal with a horse and wagon that I loaded at the start of my shift and unloaded during our route around Sowerby Bridge. The coal sacks were heavy to lift and keep balanced on my child's shoulders. The owner either- didn't notice or care that I struggled to haul these coal sacks from the roadway to his customers' houses. The time it took- to do these feats of strength was his main sticking point. "What took you so long?

Only his horse seemed to care that my body was being broken into bits for the work. His horse whinnied and then clomped his hoof as if showing solidarity with my struggle to perform tasks more suited to a grown-up after each, of my deliveries.

When not at work, I attended a village school, where one teacher taught all the different grades. He was a petty, middle-aged man with flakes of dandruff that ran down his jacket, who spent more time thrashing his students than teaching them. His broad Yorkshire accent rolled out lessons and homilies- about King and Country to school children too hungry to learn from a good teacher, let alone a mediocre one like himself. He harangued and humiliated his pupils with sarcasm and the strap.

In 1933, the man who owned the coal delivery company decided I wasn't worth the few shillings he paid me because "times were tough, all around."

My mother's boyfriend took my loss of unemployment as an indication of sloth. "Lad just doesn't want to work." Bill insisted that- I must get less food for my breakfast and tea because I wasn't earning it. "If you want to eat more- get another job." The hunger hurt me more than his lack of love or compassion. Fortunately, Alberta began to provide me food from the larder of her employer to make up for my reduced rations at home.

But I knew I needed to find work and fast, which didn't prove to be difficult. I was only a decade old but was three years into being a child labourer. I was street-wise enough to know- there'd be someone willing to exploit me- for little pay if I asked around.

Jubb's Grocers fit that bill. They were located- in the village and needed a boy to do their dog's work because the old one had moved on to greener pastures. I was hired because of my ability to lift heavy objects and take their shit without much backtalk. I worked for them after school until late at night and then for twelve hours on Saturdays. I stocked their shelves, swept floors and ran deliveries for them while- in moments of both work and rest, hatched plots to run away from my mother, Bill and Sowerby Bridge.

Thanks for reading and supporting my substack because it allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions to this newsletter help keep my housed which has become a precarious thing- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities as I age in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John