Growing up in Nazi Germany ensured my mother's post-war feminism was political and left-wing.

International Women's day draws me back to memories of my mother's wake in 1999. There, my 82-year-old Polish/Belarussian godfather approached me and- in a voice breathless with exacerbation said, "Your mother was soooo liberal."

Mum could not be anything other than liberal when it came to her attitudes about society because she knew first-hand where the road of intolerance leads people and nations.

The start of my mother's life was bohemian, socialistic and impoverished; it should have been the inspiration for the lyrics of a Kurt Weil song played in a Berlin cabaret in the 1920s.

She was the bastard child of a working-class Berlin gadfly who couldn’t decide if his ideology was womanising or socialism. Her mother was a manager for a hotel known for its cheap rooms, affordable grub, and prostitutes free of venereal disease in Hamburg's Reeperbahn district. My mum was born in 1928, and while she suckled, democracy was dying in Germany.

It wasn’t a good year to be born working class in Germany because its ordinary citizens were paying a heavy price in reparations to the Allies for being the losers in the first Great War ten years previous. But it was the best year; my mum would see in Germany until after the Second World War, as each year that followed 1928 was more unsettling than the next. 1929 was when Wall Street crashed. 1930, millions of Germans were out of work and on the breadline. 1931, the banking crisis and recession caused Germany to plunge like an elevator shorn of its cables into a Great Depression. 1932, the Nazis became the largest party in Germany's Reichstag. 1933, Hitler became Chancellor, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Had it not been for Germany's total economic collapse, my grandmother could have made it as a single mother managing a dingy motel for sailors and shady businessmen. However, the economic and political instability of the times necessitated my grandmother become the mistress of a man who could provide both physical and monetary safety during an era of extremism. As my mother said in later life about my grandmother’s lover/provider. “He wasn’t the best sort, but there could have been worse.”

Uncle Henry, as he was known to my mother, was an overweight, opportunistic importer of tobacco products. On weekdays, Henry deserted his wife and lived with my grandmother in an apartment he rented for her- located in a leafy suburb of Hamburg near its airport. On weekends, he returned to his wife and five children, who lived in a small town north of the city.

To Henry, this division of affection and time was a perfect arrangement except for one inconvenience; my mother. It’s not that he disliked my mum, just her presence in his life. “I was a talkative inquisitive child wrapped around my mother’s apron strings. I disturbed his lovemaking to my mother and his business scheming.”

Henry was good at schemes because he had convinced an importer of games, who also happened to be a communist- to sell a controlling interest in his company to him as protection against the Nazis. That same cunning had Henry arrange for my mother to become a foster child to a working-class family in the Altona district that was short of cash.

There in 1932, as a four-year-old, my mother witnessed Bloody Sunday. That was when Nazi Storm troopers shot dead communists in her neighbourhood during a street battle that lasted many hours. My mother watched unarmed men killed by Hitler’s fascists.

In my youth, she told me a lot about her past in Germany, not everything- but enough for me to find her unique and different from all the other mothers in our suburban Toronto surroundings. My mother also told me these stories of her early life in a totalitarian state because she wanted to make sense of how she ended up in Canada, married to my father. From these stories, I learned life had mapped out a multitude of destinies for her other than the one she lived.

The Nazis, however, cast the greatest shadow over her destiny as they did to everyone from her generation.

Evil was being done everywhere in Germany during her childhood. But people normalised it, rationalised it and said to themselves. “This is the price for stability. This is the price for economic growth and employment. This is the price we must pay.”

Now, as my mum grew into a teenager, she didn’t dissent like Sophie Scholl because that takes extraordinary courage. However, she tried not to conform to the norms by listening to foreign broadcasts of news or jazz. She was a problem teenager, even for her foster parents, who couldn’t handle her ”Hedda Gabbler” outbursts or her “dramatic” suicide attempt.

My grandmother’s lover had my mother exiled at the age of 13 to work on a farm for the war effort, where the farmer sexually assaulted her.

After the rape, my mother was chucked out for insubordination and indentured to a Nazi family in Cologne. But a dropped bomb from an air raid quickly ended her tenure there as it caused third-degree burns on her back that required a stay in hospital. Her roommate was a 5-year-old boy whose legs were crushed when he was buried in the rubble of his apartment after another air raid. He called her Liebchen, befriended her, joked with her, and then died painfully from gangrene.

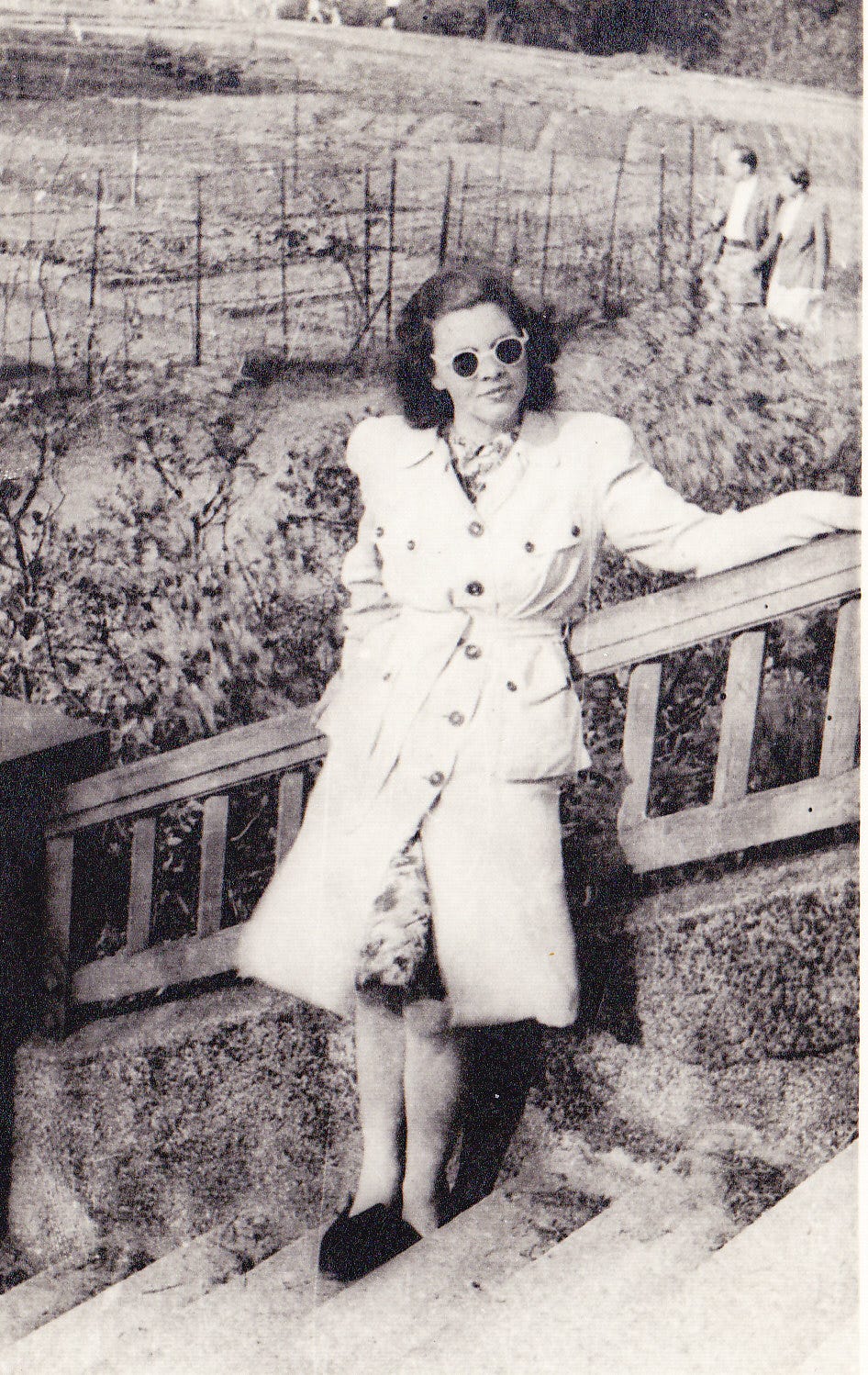

All those bits and pieces of her early life, along with the intolerance she faced for being a woman and new immigrant in both Britain and Canada- created her liberalism, feminism and also individualism. She distrusted groupthink, hated sanctimony and hypocrisy. Mum was left wing but belonged to no political party despite stumping for Labour in the 1951 election to warn voters about fascism. Yet the moments she most enjoyed were the ones when she danced to the sound of her own drummer and said to hell with the judgement of others.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John

"But people normalised it, rationalised it and said to themselves. “This is the price for stability. This is the price for economic growth and employment. This is the price we must pay.”"

Chilling. And excellent writing as always!

Great writing and reading as always. You do need to publish these all somewhere. I need to have copies so I can finally sit and read them all. Hope all well with you and yours.