So much potential, so much happiness, so much living is lost through capitalism's insistence that poverty is necessary for wealth creation. We became the broken eggs for the 1% omelette of excess. People are living the nightmare of lost hope in the 21st century because of neoliberalism's response to COVID-19, the cost of living crisis, the refugee, and the climate crisis.

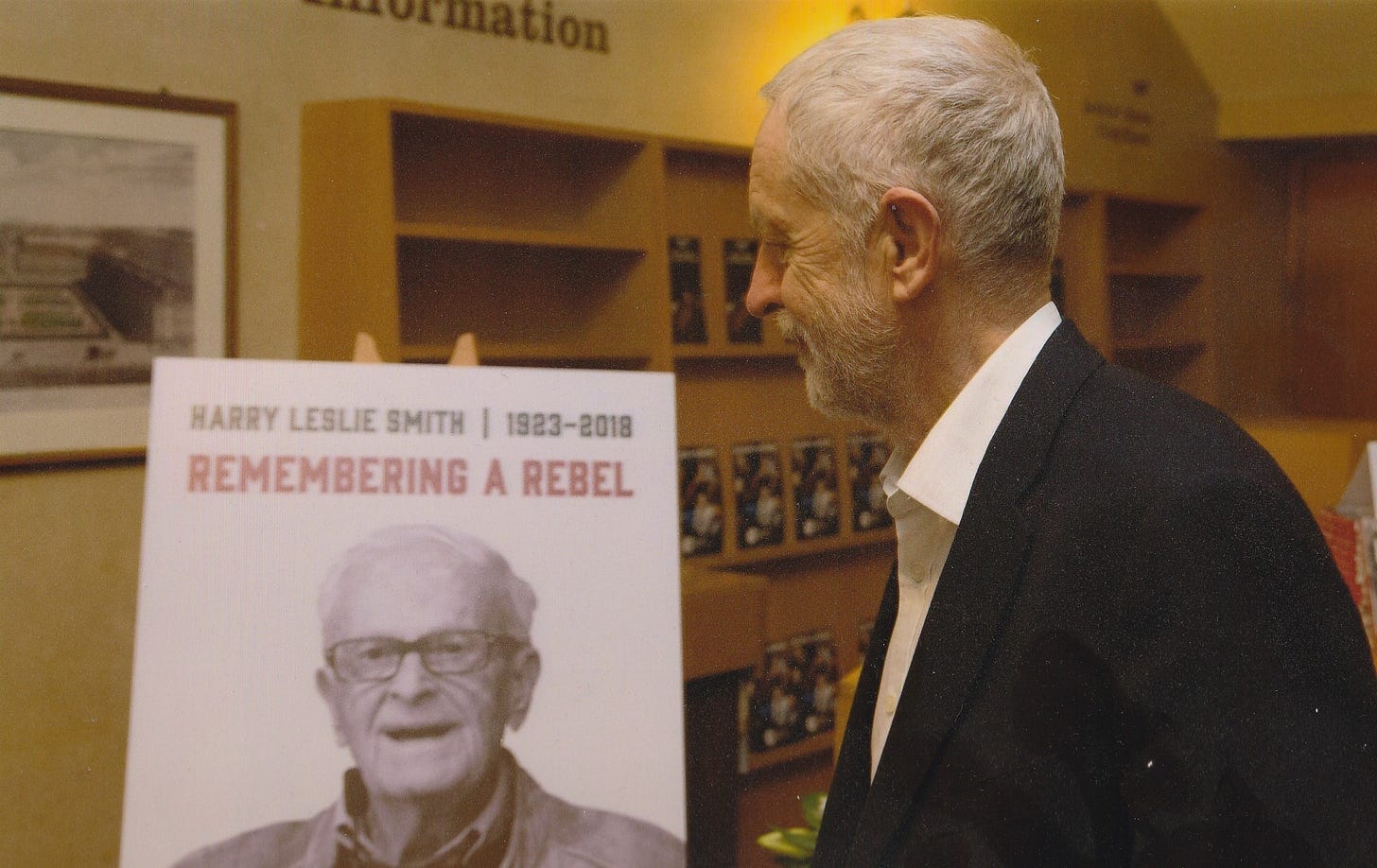

Before my father died in 2018, he wanted to demonstrate by using the history of his life and working-class contemporaries born in the early 20th century -that without a return to socialist politics fascism and wealth inequality would destroy not just our society but civilisation itself.

His unfinished history- The Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project, along with the 5 other books written during those last years of his life, and the one I wrote after his death.

For the last year, I have been refining and editing The Green And Pleasant Land to meet my dad’s wishes. Below are more chapter excerpts from it.

I have also included a tip jar for those who are so inclined to assist me.

Chapter Sixteen:

Since the age of seven, it was the same everywhere we lived, I was expected to "pay my way" as my mother put it. Bill ensured that I was motivated to do so when we arrived at King Cross. He told me me when Mum was out of earshot that like my dad; if I wasn't working I was unnecessary ballast.

"Lad, when I were in navy, lazy sods were tossed over board."

An outlet of Jubb's, a few miles from our new digs, had a help wanted sign placed in their front window for a delivery boy.

I went inside and inquired about the position. The manager asked if I could ride a bike and whether I had any issues with heavy lifting. When I said no, I was hired on the spot.

The delivery boy's job was arduous. I was tasked with loading and delivering groceries stored in a basket mounted at the top of the bike’s front tyre. Often the woven basket was laden with 60 pounds of groceries for delivery.

My route was 20 miles in circumference and led me all across Halifax and the rural areas surrounding King Cross.

I did my duties energetically and without complaint. I was an eleven-year-old boy who wanted to be known as a "good worker." It was the condition of my class that even during the 1930s, we viewed ourselves through a lens of utility to capitalism.

I understood the injustice of my servitude on an emotional level because it angered me that I was invisible to middle-class children.

They didn't see me as anything more than part of the scenery to make their lives less burdensome.

Workhorse or work boy, it was all the same to them. Their inherited wealth, father's wages, and grammar school upbringing indoctrinated them into a belief system- where they were the masters and the working class their servants.

I despised them and envied their leisure hours denied to the likes of me. While I strained to ride my overladen delivery bike, middle-class kids were off to birthday parties, music lessons or the matinee.

Sometimes, these middle-class kids tossed me the same awkward and uncomfortable glance as one would to an animal, overladen with cargo. But I was still not intellectually aware that child labour and enslavement to work through poor wages was something that could be eradicated in Britain and the world if ordinary people became militant and said. "Enough is enough."

After a few months of working as a delivery boy, the manager at Jubb’s expanded my duties to include working behind the counter. My manager liked keeping me at the front of the store as he was having an affair with one of the married female clerks and spent much time with her in the back store room.

I caught them having sex on the sugar sacks once too often. But instead of firing me, my manager gave me the task of designing the store's window display.

I became so adept at doing it, that one of my displays took second place in a community-wide competition.

Whilst working at Jubb's, I took up smoking because my manager said it would give me more energy and stop me from being hungry. Every week, I bought Woodbine's for two pennies for a packet of five filter-less cigarettes.

At break time, I stood out back, placed a fag on my lips and struck a match. The coarse tobacco soaked into my callow lungs and made my head dizzy but put to sleep my hunger pangs.

Next door to Jubb’s was a high-end chocolate confectionary shop. Their chocolates were all hand-crafted and presented in rich, beautiful boxes that were out of reach of an ordinary worker. The store’s clientele were mainly affluent housewives, with their well-dressed children in tow.

They were ignorant or indifferent to the poverty around them. They certainly perceived me as a non-entity if they encountered me washing down the stoop at the front of Jubb's.

With a reputation for excellence, the shop routinely discarded- entire boxes of chocolate that they deemed unsatisfactory. They were dumped in a bin behind the store they shared with Jubb’s.

Out back, in the rubbish bin, exquisite boxes of chocolate with bows and ribbons wrapped across their tops lay like buried treasure amidst rotting produce.

It seemed too good to waste, and many times at the end of my shift, I dove into the rubbish bin to fish out a box of chocolates. The first layers were always covered in mould, but the lower tiers were perfectly edible.

The looted boxes I brought home to share with my sister, mother, brother Matt and Bill.

We were all gobsmacked by the richness of their taste and how the middle class lived so much better than our bread-and-dripping working-class existence. A box of that chocolate if bought in the shop rather than fished from a bin was the equivalent of a week's rent for us.

******************

We needed the treat of that chocolate considering much of the time Bill Moxon's butcher shop was empty of customers. Moxon lacked the temperament and capital to be a shop owner. Without clients, Moxon occupied his time by standing outside and kicking a pig's bladder filled with water; as if it were a football until it eventually burst.

If it weren't for shady dealings in stolen beef, Bill's shop would have shuttered the first month. But it plodded on for half a year until it was closed because of rent arrears. He was the only one surprised by its failure. Moxon, however, was a man of no self-awareness because the news that my mother was pregnant with his child took him by surprise.

Mum's pregnancy didn't sit well with Bill because he was outraged by any form of familial responsibility.

Out of money and schemes, Bill buggered off. One morning, after a night out at the pub, he said to Mum,

"I’m better off without thee.”

When my mother pleaded with him to stay at least for the sake of his child growing within her. He denied paternity to it and called my mother a whore for becoming pregnant.

After his outburst, Moxon got up and left.

The morning he left, Mum looked as shell-shocked as in past moments when Moxon hit her for speaking out of turn.

Mum didn't know what to do without Bill because, since 1930, she viewed him as a life raft. Mum had abandoned our father because she believed Bill promised survival for her and us during those times of economic calamity. Mum had damned herself and us by the extreme measures she took to ensure she was with Bill.

My sister and I renounced our father to facilitate her relationship with Bill which forever tarnished our psychologies and gave us a lifetime of guilt for being part of a deed that destroyed Dad.

Mum had given everything up to be with Bill and was now ostracised by her family- because of it.

For years she had taken his beatings because he offered in return a meagre salary that paid the rent on shambolic, sub-human housing. It meant nothing to him her sacrifices. Mum was so unimportant to him that Bill abandoned her, pregnant and without income.

With Bill gone Mum warned us,

"There's nowt in the cupboard. There's nowt left but the workhouse for thee- if I don't fix this.”

My mother's warnings that the workhouse was in my future- if our luck didn't change, terrified me. My sister was less anxious about these threats because she worked full-time in a mill by then.

It did not pay much as she was only 14. But Alberta knew she could afford a room somewhere. Alberta attempted to assure me that, in time, we'd come out safe on our journey through poverty. I wasn't convinced. In my fear of being sent to a workhouse, I began to despise my mother. I blamed Mum for leaving herself and her children vulnerable. I was not mature enough to understand- working-class women had few options when it came to surviving in a harsh capitalist world dominated by men.

Without Bill, Mum found respite, or courage, from life without a breadwinner through drink. At the time, I thought it was cowardice and escapism- that drove her down to the pub. I believed she was wasting what little money we had on selfish pleasure, and I openly attacked her for it.

Later, I learned her trips to the pub were a drastic action to keep us together and housed as a family. On occasions, Mum sold herself for rent to men looking for sex. It was not an uncommon thing for working-class women in the 1930s.

Having to exchange sex for money took its toll on my mother's emotional balance. During the day, she suffered from panic attacks which made her feel like she was dying from a heart attack. I thought it was simply high dramatics and cries for attention.

There were many times when my sister and I hauled our mother from between bins outside our home when she came home blind drunk from the pub. We'd drag our mother indoors and hoped that no neighbour had witnessed her fall or spied us transporting Mum into the house drunk and lifeless. Mum would sleep it off and wake in the morning bitterly angry at herself for scraping rock bottom.

In January 1935, a few weeks before her pregnancy was due, Mum told us she was leaving King Cross.

"I will find Bill and fetch him back to us."

Mum left for Bradford to look for Bill with money scoffed from my piggy bank. She busted it open with a butter knife held in a hand overcome by desperation.

"You'll be right as rain- because you can make more of it."

She took our baby brother Matt with her and deposited him at her sister Alice the only sibling that still talked to her.

Chapter Seventeen:

When Bill left Mum he went to live in our old neighbourhood of St Andrew's Villas, in Bradford. He had returned to work as a “pig man” at a nearby farm. Mum went to his doss to reconcile but Bill wanted nothing to do with my mother.

He told her to go home to King Cross. Instead, she took a room in one of the doss houses that littered the street and there Mum gave birth to her new child on January 13th 1935.

Moxon was initially unmoved by the child or Mum's demands for him to acknowledge the child as his son.

Mum didn't leave Bradford until Bill agreed to register the child and accept it as coming from his blood and bone. He only did so on the proviso the child be called like him William.

During that time away Mum lived off the charity of her sister Alice. She even received- some help from my dad who still lived in a doss on that street. He gave her what little he had despite his abandonment by her.

When Mum returned to King Cross after a three-month absence with her son "Bill Junior, " she acted as if she had only stepped out for a pint of milk and not abandoned her other children to fend for themselves for 90 days.

Her "Come and say hello to your new brother,” revolted me because Bill Junior was another mouth to feed.

He was not like Matt, who I saw as my brother, and he was blameless for his condition. Irrationally, I saw Bill Jr. and my mother as conspirators in our family’s unravelling. I never accepted my youngest brother as anything but an impediment and an intrusion into my life. I was not kindly possessed to having more responsibility thrust upon me, with this desperate child, in this desperate household.

Fortunately, I had found a means to escape the cries of a newborn and my mother's cries for assistance at the library in King Cross. It became my real school, as well as an escape from the greyness and the emotional hunger in my life. In my off time, I would go to the library, which was housed in a Victorian building near our house.

I perused the shelves of books filled with strange titles. I grabbed novels that caught my fancy and indulged my mind and imagination. With Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable, I suffered Jean Valijean's torments, indignities and poverty- and compared it to my own sorry state. In The Count of Monte Cristo, I witnessed injustice and the fight to right the wrongs of birth and legacy.

For the price of a library card that cost a few pennies, I was transported across the world and sat at the feet of great thinkers, poets, playwrights, novelists, historians and political advocates for change.

I spent any moment I wasn't working or at school enraptured in the poems of Wordsworth, the plays of Shakespeare or discovered by reading books like The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, and the Communist Manifesto that the ordinary worker was a commodity abused and exploited by the rich.

I was comforted, strengthened, befriended and revolutionised by books, whose ideas spoke to me. They eased my loneliness and gave me courage and resolve. They gave me hope that there was a world outside my hunger, poverty, and broken family waiting to welcome me.

The books I read in 1935 and afterwards did something else for me; they politicised me. I began to formulate in my childish mind that the circumstances of my poverty weren't the fault of my shortcomings or my parents but because society was rigged to favour an entrenched entitled class.

Books- made me aware that poverty wasn't the natural order of things but a perverse and cruel means to control and subjugate ordinary humanity.

Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

That's why the tyrants ban books.

The old library in King Cross is closed down now and empty but there's a new one nearby. I’ve been in both and I liked old one better. I'll think of Harry sitting reading in there next time I go past it on the bus