His humanity, and talent as an artist defined my brother's life not his mental illness

The life and legacy of Peter Scott Smith-good egg and damn fine artist.

My rent is soon due, and I should have been spending this day like a desperate character from the novel Berlin Alexander Platz on a mad pursuit for cash to keep a roof over my head. But I couldn’t because I remembered today was my long-dead brother’s birthday. The memory winded me, and I rested in the company of pleasant and unpleasant reminiscences from my past.

Peter’s been dead these thirteen years, but not a day goes by where I don’t spare a thought for him. Had he lived, this would have been his sixty-third birthday. But as he died at fifty, he missed growing older with his wife.

Peter died too young. But even staying alive for half a century was, for Pete, as arduous and precarious as surviving a Mount Everest climb without oxygen cylinders because he was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his twenties and then pulmonary fibrosis in his late forties.

In the last year of his life, he told me he couldn’t remember a time; when he didn’t hear voices in his head mocking him and abusing him by attempting to distort his reality.

When I was twenty-two and Pete twenty-six, I wouldn’t have guessed mental illness stood around the corner for him, preparing to rob him of his sanity and a normal progression through life. He was an artist on the verge of recognition. He had an excellent job as a scene painter for the Toronto ballet company, and his social life was full and exciting. I both envied and loved my brother. He introduced me to the music of Elvis Costello, the films of Fellini, the socialist historian A.J. P Taylor, the novels of Steinbeck and scotch whisky on a Saturday night whilst listening to jazz. He was cool, confident, generous and kind. Peter took after our father when it came to loyalty and hard work. He was a non-conformist who marched to the beat of his own drummer and wasn’t afraid to stand up to bullies.

Schizophrenia ended much of what made Peter Pete when he was twenty-eight. Had my parents not taken him home to live with them, I don't doubt my brother's life would have ended in suicide because he was terribly ill. My parent's stood by Peter, during the worst of his journey across the terra incognita of schizophrenia. But it took a toll on them and our entire family as severe mental illness is a brutal disease that tests even the strongest love.

At first, I failed the test. I tried to straddle accepting my brother was mentally ill while simultaneously denying his illness to others. It was selfish because I wanted my early twenties to be about me and not the traumas others in my family struggled with. Eventually, I came around. Yet, I mourned for the brother I lost to mental illness, and grieved for what I felt my own life lacked because my parents could not be there for me during my times of need.

In time, I patched things up with Peter, and we formed a brotherly bond that was more emotionally honest.

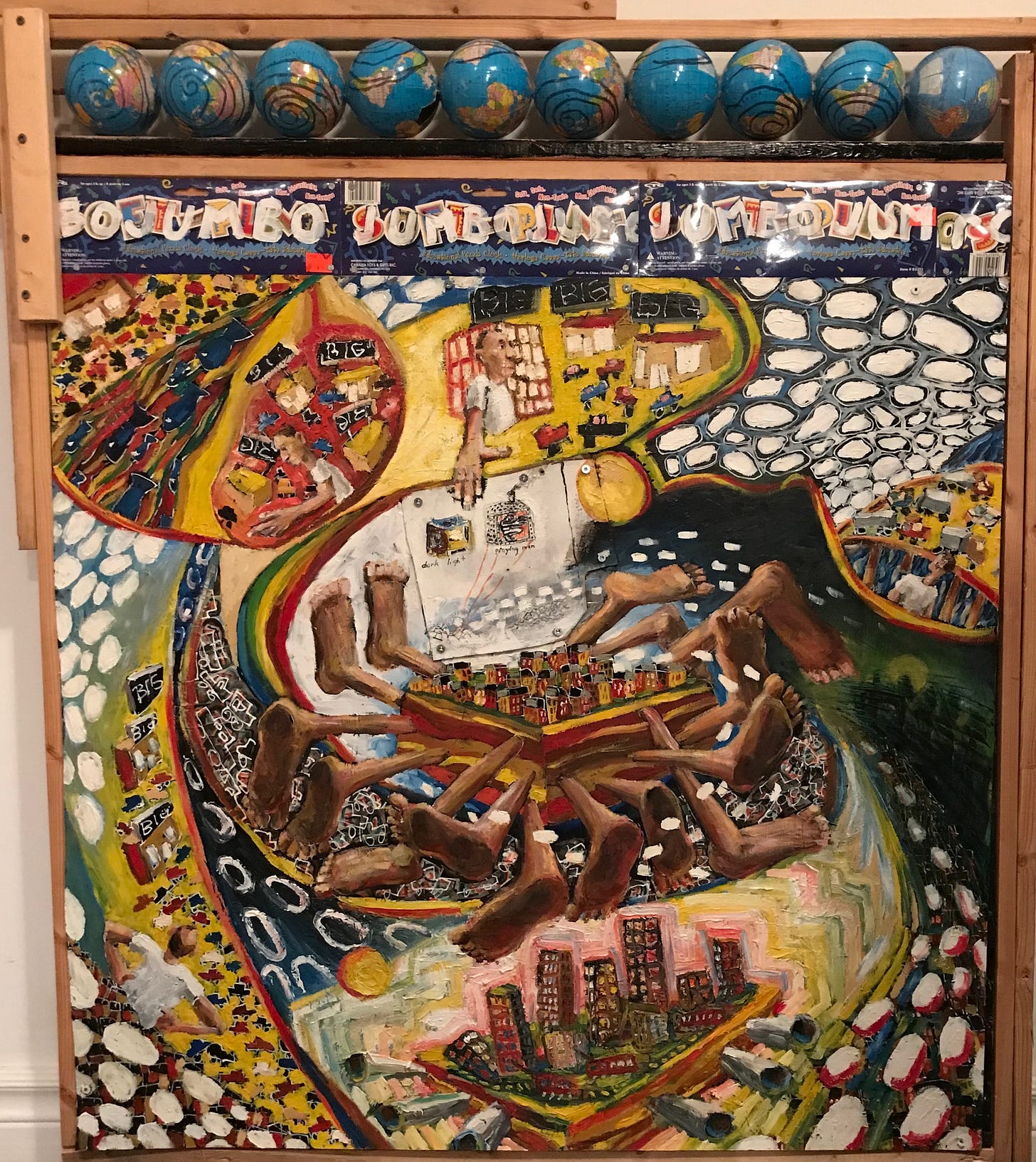

Peter's mental illness began to stabilise, and my dad helped that happen by encouraging him to resume his artwork. It saved my brother because Peter used his artistic talent to document the harsh journey schizophrenia compelled him to take across the geography of his spirit. There was a tragedy in Peter's artwork. But there was also so much beauty, love, rage, desire, joy, and humour in it.

My brother used his art to bang against the bars of the prison his mental illness had sentenced him to. He demanded a purposeful life that had love in it, and some degree of independence. In many ways, he got that life. He was able in 1999 to marry his girlfriend, and they moved into an artist co-op housing complex in Toronto. Peter began showing his artwork again, and he worked as an artist mentor with other mentally ill people to help them use their art to find expression for the traumas endured because of their afflictions.

Everything was gelling again for him. After decades in the wilderness, Peter was on the cusp of being discovered again by the art world. My brother was gaining recognition for his talents and being written up in art magazines as well as winning juried art competitions. Life isn't fair because, at forty-eight, he developed a cough he could not shake. He blamed it on cheap cigarettes, bought on the black market. It was not the cigarettes. It was something worse; his lungs had become fibrotic. They were losing their elasticity. He had a disease known as IPF or interstitial pulmonary fibrosis.

When he turned forty-nine, Peter’s breathing grew worse. Peter spent that year in his studio trying to nail down more of his story onto canvass or wood carvings. He had a premonition of his death because many of Peter’s works show him on a hospital bed with a tube coming out of his throat.

On Peter’s 50th birthday, he was in an ICU. Peter knew that he was dying, he just didn’t let on to me, his wife, or our dad. He pretended that things would be all right despite needing a respirator to keep his lungs breathing. I almost believed him until Pete indicated to me with hand motions to remove all the photos in the room except those when he was a young child. I knew then he wanted to fix his eyes and imagination to a time when he was not under siege from mental illness or dying lungs.

I wish my brother could have seen sixty-four because I enjoyed his company so much. It would have been nice to share a beer and memories from our long-ago past. Some of his artwork adorns the walls of my apartment. It consoles me because, in it, I see the moments of his life through his eyes rather than mine. His artwork reminds me of my purpose in life. It reminds me why I committed what's left of my life to preserving my family's working-class legacy of socialism, art and literature of lives lived well in harsh conditions. So, my brother, here ends another year you are dead except in my heart and memory. Three cheers for the days when you were alive, along with mum and dad. When the hours, we spent together were filled with both sunshine and storm. Or to quote Peter, who said when near death, “It’s been a fucking blast.”