History teaches us-Humanity can only live for so long in chains before it rises up in revolution.

The citizens of the 21st century have forgotten their working class past and because of that our societies stand at the threshold of authoritarianism. I have no doubt sooner rather than later, we will walk through those doors that lead to dictatorship. What we are living in now will get worse and it will take more than a generation to change. But change will happen because history teaches us- humanity can only live for so long in chains before it rises up in revolution. When the uprising comes it will need to have the grit and the outrage that past generations had who fought to take their lives back from being owned by the entitled.

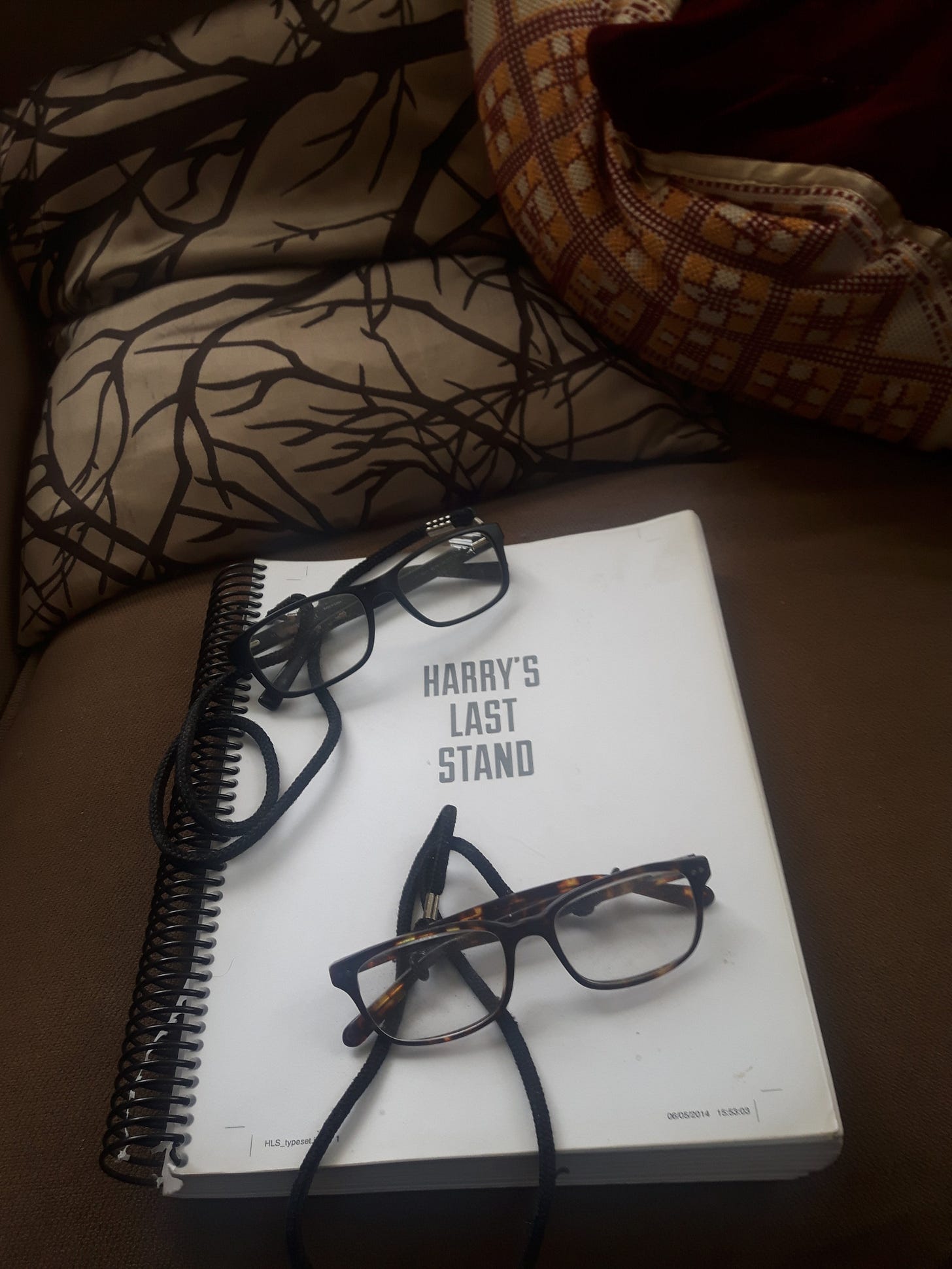

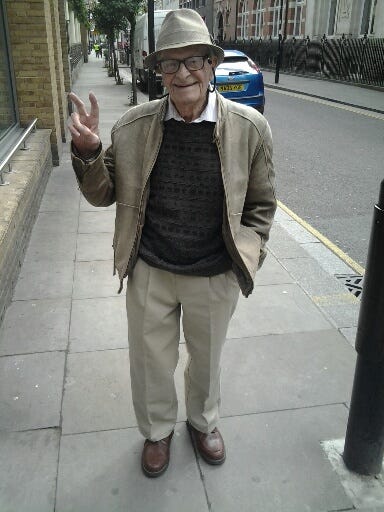

Works like the Green & Pleasant Land are more important now than ever now because they tell a story about the lives of working class people living during a time of political and economic extremities. They are proof that ordinary humanity can seize destiny and make a present that is fair to all. The Harry’s Last Stand project which I worked on with my Dad for the last 10 years of his life was an attempt to use his life story as a template toe effect change. His unpublished history the Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project. I have been working on it refining it and editing it to meet my dad’s wishes. It’s almost ready. This week I’ve been dropping the first 25k words of it. Today is the 3 part for your consideration.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going and me alive is greatly appreciated. So if you can please subscribe and if you can’t it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury. But always remember to share these posts far and wide.

Chapter Seven:

Mum's desertion of our family for life down south with the Irish Navvy O'Sullivan was a separation that made my heart ache worse than if she had died. To my childish eyes, her decision was voluntary, selfish and cruel. It took me decades to understand and forgive her logic. Mum's leaving like later on my father's involuntary leaving created a host of separation anxieties which plagued my life and relationships with others. I became a person who did not trust and found little profit in forming bonds with other humans.

After Mum bolted, Dad pretended his wife was on holiday- and we must make do without her for a brief time. The schedule for her return was a constantly changing schedule for Dad. He simply didn't know if she was ever coming back at all. Sometimes, it was "Your mum will be home tomorrow"- other times, "She'll be home next week." None of us knew if her plans would ever include us, again.

My sister Alberta wise beyond her 10 years and as fierce as a lioness, thought it best after our mum left that I was toughened up. My sister tried to be a surrogate mother to me and an emotional crutch for my dad. It was a horrible burden for a little girl to be forced to bear.

Every night, whilst we snuggled together for warmth at bedtime underneath blankets of old coats, Alberta made plans for us and devised schemes to scoff food from neighbours. Alberta taught me the ways of a street urchin to ensure I'd always find food to eat. It was strange mothering because Alberta taught me what to look for when we scampered through the rubbish bins outback of restaurants. She instructed me on how to judge like a diamond merchant can spot flaws in a cut gem; what half-eaten chop was rancid and what was fresh enough to eat without becoming sick. She mothered me with affection, harsh words, and sometimes even slaps to keep me alive. We laughed together, stole food together, and during our childhood supported each other emotionally because the adults in our lives were incapable of giving much back because the world had been so unspeakably cruel to them.

She was good at convincing lodgers who were famished themselves to share their bread and drippings with us. My sister taught me to sing songs like Danny Boy to ensure that we paid for what we were given.

When my mother left us, The Great Depression was in its second year, and industries of the north: coal, steel, and textiles, were in a state of collapse. Like falling fruit to the ground, Yorkshire, in 1930, withered and rotted. Britain's unemployment rate exploded to 2.5 million workers, who were allotted a dole for fifteen weeks. It was substandard government assistance; afterwards, they went hungry, or their kids learned to rummage through the rubbish bins of their towns as I did.

In Bradford and other Northern towns and villages, the effects of malnutrition began to creep across every street corner. Rickets, TB, and death from starvation were not freak occurrences but living experiences for the working class. Disease was rife in all the towns across the poverty-racked North. Early death was considered normal for the working class because healthcare was private.

Alberta and I, followed by other children, chanted down squalid streets blanketed in want and hopelessness-

“Mother, Mother, take me home from the convalescent home.

I’ve been here a month or two, and now I’d like to die near you.”

When my mother left, it every day had a sunless quality to it. I didn't confide in anyone, my fears, and my terrors outside of Alberta. I knew not to trust others because them knowing my mother had done a runner would put my sister and me in further jeopardy.

Neither I nor Alberta told the nuns our mum had gone for a prolonged naughty weekend. As for the priest at confession, we kept schtum because my greatest fear wasn't an eternity in hellfire for lying to God, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit but having the state put my sister and me into a foundling home.

My family had slipped beneath the waves and were lost because not the government, society, not even more affluent members from my dad's side of the family were prepared to rescue us. We were transient players on this mortal coil destined to be ground into nothingness by the pestle of capitalism and the greedy hands that turned it.

That year when I reached my seventh year of life, I had neither the time, the skill set or a full belly to do my schoolwork. I fell behind the rest of my classmates in arithmetic, history, and grammar. The nuns were unforgiving to those who did not know their assigned lessons. Despite my mother's threats earlier on in the term to punish those who punished me, I was slapped, strapped, or humiliated with harsh words of "dummy, stupid" and "imbecile" by nuns whose stomachs bulged impregnated from over-proportioned meals provided by the alms of Bradford's poor catholic brethren.

After a few months, I had grown to accept Mum was gone. But then she returned one day as if she had never left us. It was unreal to see her again after being absent for so long. Yet one day Mum stood to greet us at the entrance to our room in the doss house. Shakespeare's Winter's Tale for the working class, except this was no fairy tale with a happy ending but another chapter in the unfolding nightmare of our family's collapse into poverty caused by the Great Depression.

For her return to our family, Mum wore a floral dress that sparkled against the decades of grime and grease on our walls. She held a pineapple in one hand as if she had just arrived home from Captain Cooke’s expedition to the South Seas whilst in the other, my mum carried “authentic Irish soda bread.”

My father looked at her, his mouth agape, speechless at her return and the condition she returned to us in. She was changed. Soon, we would learn how changed she had become down south by O’Sullivan’s doing.

That night Mum made our tea and confessed as we silently ate the soda bread dipped into a weak meatless broth that she was pregnant. My father was more distant than normal at that meal and for days onward as he was processing in his 19th-century brain his cuckolding. As for the pineapple, my mother never offered it to us to eat. Instead, my mum showed it around to the other lodgers to demonstrate the wonders and oddities available to the residents of London.

Chapter Eight:

Home, spurned by O'Sullivan and pregnant with his child, Mum was in a sorry state. She returned to the doss with the same air about her as a captured prisoner marched back to their cell. First, there was initial bravado. Quickly followed by dour silence after she began to contemplate a life sentence behind the four grim walls of poverty.

No one took pity on her- either in our family or the outside world. Instead, the neighbours put two and two together about the reason for her long absence from the doss that coincided with O'Sullivan's sudden disappearance.

Once her pregnancy began to show, they tittered about "naughty weekends"- and then Scarlett lettered my mother- whilst making cruel jokes about my father "leaving the back gate open".

You can't stop gossip, and you can't stop people poking their noses where they shouldn't go. Everyone had to have a whiff of my family's troubles to pretend to themselves their own lives didn't reek as much of squalor, disappointment, and loneliness.

Near Mum's death, forty years after her tryst with O'Sullivan, she confessed the bolt down south in the winter of 1930 was because the "navvy had got me in the family way." My mother hoped a new life could be forged on the outskirts of London from the ash leavings from her one up north.

It didn't work out because nothing ever does for the poor. O'Sullivan was as bad at holding a job as my father was at finding one. Naturally, that led to arguments and the cooling of their mutual desire for each other.

In the 1960s, when all my mum's passions were spent except self-recriminations, she admitted to a sister that O'Sullivan's affections for her were "unsteady." Any love or loyalty O'Sullivan might have had for my mum did a runner at the prospect of responsibility for her and his child. The notion that his wages earned from the sweat of his brow couldn't be used for craic down at the pub because he'd helped make a baby was a language he refused to learn.

Like all her pregnancies, it wasn't a joyful time for Mum. Another baby was just another mouth to feed in a household of hungry, underfed mouths. It was made worse because my father was shamed and humiliated by her affair with O'Sullivan. He resented Mum and despised himself. As for the child growing inside my mother's womb, he didn't hate it, but he didn't like it either.

Nightly, a dense fug of acrimony from screaming bouts between my parents hung heavy in the air of our squat doss house room. My parents raged at each other from teatime until bedtime. They cursed each other about being a jobless husband or a wanton wife. The din from them was so loud, and persistent neighbours pounded on our walls for my parents to "pack it in."

Even as I approach the last breaths of my life, the roar of outrage, fear, and desperation my parents expelled when they awakened in 1930 to the reality their existence was doomed to perpetual unhappiness crashes about in my skull like heavy surf during a storm.

There was no love, trust, or hope left between them, only animosity. Their sixteen years of marriage were based upon a belief; that things could work out and even get better if they just held out long enough for the tide to turn. However, the opposite occurred; the longer they stayed together, the worse things got. Mum knew it couldn't go on that way- for much longer. We were sinking lower and lower into the mire of a poor relief that kept you alive just enough so that you knew how much of existence was an awful losing battle for the unemployed.

To make it out of the Great Depression- one of us had to be forsaken.

Mum chose to save me, Alberta, and herself whilst Dad was to be the one abandoned as if he were excess cargo, on a ship in danger of capsizing. My sister and I didn't have any say in the matter because our mother knew we'd have fought her tooth and nail to stop her sacrificing Dad. So instead, Mum used emotional Dum Dum bullets that she shot into my heart and Alberta's which exploded out a shrapnel of fear that unless we followed her plan, we would have no parents rather than only one.

Mum vocalised what should have remained silent within her adult mind and heart. "It's to the workhouse for thee and thy sister if your dad doesn't find work." At bedtime, I'd close my eyes and wish for sleep to cleanse her words from my imagination. But the feelings the words left in my small boy's imagination never departed. Like Prometheus learned the knowledge of fire, my mum gave me the knowledge, that nothing was secure in this life- and love does not outlast famine.

It terrified me to understand at the age of seven, I was not safe- and could be abandoned, shorn from my family at any moment.

In an age when millions of men were out of work, my mother's only plan to turn her pig's ear -of a life- into a silk purse was to find a man, unlike my father, who was employed. To initiate her machinations, we had to leave our current doss. Everyone there knew our family dynamic and working-class misogyny had already pilloried my mother for her dalliance with O'Sullivan. But since my parents were seemingly still a couple, albeit one, who had a nightly- riotous barny, their outrage was not hot enough to burn my mum at the stake.

The working class in 1930 did not divorce because women were still considered their husbands’ chattel if not by law by social convention. For Mum to openly cuckold Dad would have branded her a whore and an outcast even in Bradford's down-and-out underworld. Any attempt for my mum to attach herself to another man had to be done under the ruse that she was widowed, and my father was my granddad. For Mum to accomplish her task of familial reinvention we had to migrate to another low-end part of Bradford and so we did.

Dad was quiet on the night of our flit while we walked on cat’s paws across streets smeared in gaslight towards our new residence, Dad was quiet. He was surrendered to what we were about to learn Mum had drawn up to be his end.

Mum said my sister and I were for the foundling home if we didn't do as she told us. From now on, our dad was to be called granddad. To not do so guaranteed my sister and me a one-way trip to the workhouse where we would have not even one parent.

Alberta fought a bit against our mother's new directive, whereas I surrendered to it.

I joined this conspiracy and pushed my dad to the periphery of my life when in the company of strangers because I was so fearful of ending up like my sister Marion, who had died in a workhouse. Like that, I let go of someone I loved. I betrayed them and ignored their place in the hierarchy of my affection because someone else I loved said it was necessary to do this to save me and them.

Our new abode on Chesum Street was arid of kindness, and hope burned as low as the sputtering gas light that cast our one-room squat in despairing shadows.

On Chesum Street, we didn't mix or socialise with other doss house residents like in our old slum. It seemed best to keep as far away from them- then let slip that the old man who lived with us was our dad rather than grandad. My only escape from the misery that surrounded me and the lie I told was to forage through the streets of this slum, looking for diversions as a damp summer sun began to unfold itself around Bradford.

Chapter Nine:

The summer of 1930 was harsh and hungry for Britain's working class.

There was no smell of warm rain on the grass that summer. There was no taste of Dandelion and Burdock pop chilled on a cellar's stone floor to quench your thirst.

Instead, summer reeked of mouldy potatoes fried in cheap margarine washed down with tea made from leaves flavourless from reuse.

On those long sunlit days, desperation calved in Mum's consciousness. It stumbled forth into the world, wet behind the ears, but it soon matured into a concrete idea to dump my father and find a man fit enough to do a day's labour.

As for Dad, resignation to his fate germinated and grew deep roots within his soul. Dad took the role Mum had cast him, like an actor desperate to play any part for a bit of the limelight. He was now our "granddad," in public while Mum pretended to be a young widow pregnant with her dead husband's child.

It was an intricate, sad web my mother wove. Eventually, it would trap not only her desired prey but also Mum. She never escaped how she abandoned my father or the guilt it produced for being compelled to concoct that lie to ensure some sort of future for her children and herself.

Like all the seasons I lived through during my boyhood, it was my sister, Alberta, whom I looked to for companionship and mentoring. She was my best teacher on how to survive the unrelenting cruelty of poverty in the 1930s.

Alberta was wise to the streets and wise to the machinations of adults. She taught me, in winter, how to forage through restaurant bins for my tea. Now, in summer, she showed me the ropes on the best ways to harvest specked fruit that the mongers binned.

But shop owners did not take kindly to kids, who came from the barren land of doss house Bradford nicking dented and bruised fruits that were rubbish to them.

Alberta lectured me on the need for speed and quiet when we dug through refuse to pick the well-ripened fruit- that when we bit into it- dripped sweetly into our empty stomachs.

When darkness came to the day or the sun rose on it, my childhood, that summer, was shaded in hunger. But also, I felt as only a small child can, wonder at the mundane and profound sights and events occurring all around me.

In that long ago time; I learned what I have known and cherished ever since, there is magic to being alive and aware.

Our street, Chesham, ran onto Great Horton, which ended up in a large open field called Trinity. One afternoon, my sister and I heard rumours that a circus had set up their tents on the common.

Alberta and I made our way up the street, where we discovered that the clearing tents had been erected. There was a sound of hammers being struck on tent pegs while the foreman swore at workmen to be "quick about it."

Not wishing to be discovered, Alberta and I went to the opposite end of Trinity Field. There, we were camouflaged by tall grass. In the distance, I heard the sounds of exotic animals bellowing from the field. We crouched on our hind legs and strained our eyes, hoping to catch sight of this mysterious world being built around us.

The odd elephant trumpet made our mouths drop open in surprise. I was tinged with mild fear, wondering if the mighty beasts could break loose and trample us hidden in the brush. An hour had almost passed, and I grew restless. I was about to ask my sister if we could go when suddenly, Alberta began to shake my shoulder,

“Harry, Harry, come and look.”

Outside one of the tents were three beautiful, lithe Burmese women whose necks were wrapped tightly with gold bands. Near them, jugglers began to practice their act. It was a cacophony of different voices, with different accents, different attitudes, and different lives from ours in the slums of Yorkshire. Further off, I heard lions roar and in my imagination, it was lion speak for "bugger off Bradford."

Everything I saw that day crouched and hidden at the edge of a circus in the long unkempt grass of the common- was enticing, forbidden, and beautifully foreign to the world as I understood it.

Chapter 10:

Mum was in her eighth month of pregnancy during the dog days of August in 1930. The weather was sultry, and our neighbourhood stank of people's sweat and under-washed clothing.

Our threadbare squat on Chesum Street was unbearable from the heat of the sun and the burning rage that exploded out from my mother's mouth to my dad for the injustice of our poverty.

She was short-tempered with Dad because instead of finding fault with capitalism for causing the Great Depression, he was made to blame for our personal destruction.

Hungry, angry and pregnant mum was a beast best avoided. So, I did not complain when I was packed off to spend the remainder of the summer in Barnsley with my grandparents. Alberta was not sent with me because- being ten- she was considered old enough to work as a part-time laundress, which provided extra pennies to afford bread for the nightly tea of drippings.

In a few months, and to my great despair, I was also destined to be pressed into child labour to prevent my family from becoming utterly destitute.

Mum walked with me to the station, where a bus to Barnsley awaited. I carried a sack packed with a change of clothes.

My mother barked at the bus driver, the correct stop for him to let me off at.

"Uncle Harold will meet you where the bus drops you off and walk you to Grandma Dean’s house.”

My uncle Harold, as promised, was there waiting for me when my bus reached Hoyland Common, near where my grandparents lived.

Harold was thirty years old and thin as a rail that others joked the sledgehammer he used at the coal face was heavier than him. He spoke to me as he did to adults in short, brutally sarcastic sentences. Harold was married to Ida, whom he adored because she softened the harsh edges of his personality. He, Ida and my uncle Ted lived with my grandparents.

Harold did not hide from me his detestation of my mother.

At each street corner, Harold called Mum a whore, bitch or something else equally offensive.

My grandparents lived on Beaumont Street in a two-bedroom tenement house. It had a ginnel leading onto a back plot where a privy and small vegetable garden was located.

When I arrived, my 73-year-old Granddad, Walter Dean was fast asleep on a chair in the parlour.

He was retired, but before old age allowed him to slumber his last days away, he was a miner and a soldier for Queen Victoria.

He never saw battle, but you would have never known that from how he talked about life in the Artillery.

He served in India in the 1890s. He was an oppressed working-class soldier who oppressed others in Britain's pursuit of Imperial and economic domination- across the world.

Grandad spent ten years in India and departed the military, with no trade to enhance his earning potential on civvy street to make life easier for himself, his wife and seven children.

He didn't think much of me because I didn't think much of the medals he earned by taking the Queen's shilling when he showed them to me one night before bedtime.

Like Harold, my Granddad didn't like my mother much either.

From a child’s perspective, my grandfather resembled a gruff walrus who laboured to stand. He believed in monarchy, empire and the class system, where he was proudly at the bottom of it.

My grandmother, Mary Ellen, like my grandad, held strong opinions on my mother, which were generally negative.

She always wore petticoats and a heavy wool dress that swept the floor around her as she walked.

She never raised her hand or voice in my direction, nor did she hug me. My grandmother was aloof, set in her ways, but that didn't bother me.

What was more important than love at that time in my life was food and that was plentiful in my grandparents' household. That I didn't need to hunt for my tea by scavenging through restaurant rubbish bins seemed miraculous.

There were three meals a day for me to eat was a novelty to be savoured.

During those weeks I spent at my grandparents' house in the summer of 1930, Uncle Ted was the one whose company I enjoyed the most. He possessed a gentle quietness, which I found appealing coming from a household filled with- so much hidden noise and anger.

Later on, when Ted retired from the pits, in the 1950s, he took to the open roads in summer and autumn with a horse-drawn caravan won in a card game.

Ted was in charge of tending to the vegetable patch behind my grandparents' house. In the mornings I'd find my uncle carefully and solicitously weeding the garden.

He let me eat ripened fruit from the small plot, which I savoured, remembering how in June; I stole apples from fruit mongers.

Ted did not speak much, and when he did, everything was in short syllables, “mind this” or “yer alright there.”

But it was spoken from a calm river inside him, which relaxed me.

Harold's wife Ida worked as a bookkeeper on a large industrial farm and lodged there on weekdays. She was revered in the family because she had a trade that used its brain rather than brawn. Tragically, she died young and left Harold a widower for 50 years before he died in 2004, hateful of everyone in the world for scoffing love from underneath him.

Ida gave me the means to learn one of the most valuable skills a poor lad in the 1930s could acquire; the knowledge of how to ride a bike.

Ida lent me her bike and, with it, gave me the freedom to roam far from the troubles of adults around me.

The only instructions Ida gave me on bike riding was to pedal as fast as my legs would allow me. The first day on it I suffered, scrapes, bangs and bitter disappointment that riding a bike was harder than it looked.

By the second day, I was able to keep on the bike and keep it steady for longer periods.

Many attempts and many aborted take-offs would ensue. But gradually, I developed my wings. I was able to pedal and remained balanced and aloft for longer periods.

I was ready to discover the hills and dales surrounding my grandparent’s house. I’d spend my mornings and afternoons riding this bike. I was free of the burdens of hunger. I was away from my parents' despair and hunger for better lives.

I was free of my own sense of shame because of our poverty. On this bike, I could pedal faster than the storm clouds of the Great Depression all around me.

As with all things in my early life, these sheltered moments of calm were brief. The summer winded its way through my grandparent’s house on Beaumont Street until one morning, it all ended with a "Time to go, lad," from Uncle Harold.

I returned to Bradford, where my sister patiently waited for me at the bus station. We walked home in silence because I was afraid to ask if things were worse with my mother and father.

Summer had turned into fall.. Breadlines increased as the dole dried up. The working class, particularly my mother hurled invective at Prime Minister Ramsey Macdonald and his betrayal of the people by signing off on Tory austerity.

More workers were sent home from their jobs because the politicians refused to support reconstruction projects or stimulate the economy. Now, it was time for the real famine to commence in Britain.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John

A very enjoyable read and thought provoking.