However you choose to pacify the wolves at your door, it's only temporary during an eternal cost of living crisis.

I am not the exception to the rule. Many live similar lives of quiet and not-so-quiet desperation because of a worsening cost of living crisis.

I was in stitches of laughter and rage when I learned a billionaire owns Keir Starmer and gave him 30k pounds last year to buy clothing. I don't think I have spent even £100 on kitting myself out in the past two years. One plus about getting cancer was, I lost enough weight and now fit into my father's shirts that I didn't throw out after he died.

However you choose to pacify the wolves at your door, it's only temporary.

There is no time for leisure, long-term plans or extended periods of enjoyment. Each crisis you face has only two solutions- fight or flight.

It's the physical and emotional exhaustion you get from trying to mount a defence against the cost of living crisis. It turns everything around you into 's a Soviet grey world that feels hopeless stuck and unchanging.

I have two days to pay the rent. It is never much to bridge the gap. But if it isn't covered the path to my eviction begins. So, it's a worry that is always at the back of my mind, nagging me with anxiety that moves between the volume of a whisper to a shriek depending on the time of day.

I am angry at myself that I haven't finished the edits to the Green and Pleasant Land which has about 40 pages left to refine. It should have been done by spring but there is always some other writing that had to be done in the hope of obtaining new paid subscribers. IT works to a degree the sub stack paid out about 15k Canadian over the last 12 months. However I only have that and my $300 a month pension, old age pension. It becomes more at 65 but that is 4 years down the road. So, I am well below the poverty line.

That's the rub because the Green and Pleasant Land will pay decently when published. But until then I need to do all these other bits of writing to sell myself and my dad's legacy to the public.

After the Green and Pleasant Land is complete hopefully by my birthday on October 22nd, I can begin assembling the other projects I have on the back burner for the Harry's Last Stand Endeavour.

I don't want to lose the optimism that remains in me that gets me out of bed each morning to work on all that was set before me when Peter died and I choose to save my dad from an end as lonely as his beginning.

I think this quest of mine is worthy for the end stages of my life no matter if it's shorter or longer than I anticipate existing.

Remember to subscribe if you can because I'd like to finish the job I started with him and remain housed. Being diagnosed with rectal cancer at the start of the pandemic, along with a diagnosis of lung disease in 2023, altered both the trajectory of my life and the prospects available to me.

I am including for today's post a chapter selection from my book Standing with Harry. There is a tip jar for those inclined.

Chapter Two:

A Time that is gone.

Dad,

I dreamt of you again, last night. And, in those moments of sleep, you were alive and three-dimensional. But when morning and consciousness returned, your image trailed off into the ether, the way smoke from a match, after being struck, drifts, and disappears into the air. To wake was to be startled by the sadness of knowing, you are dead.

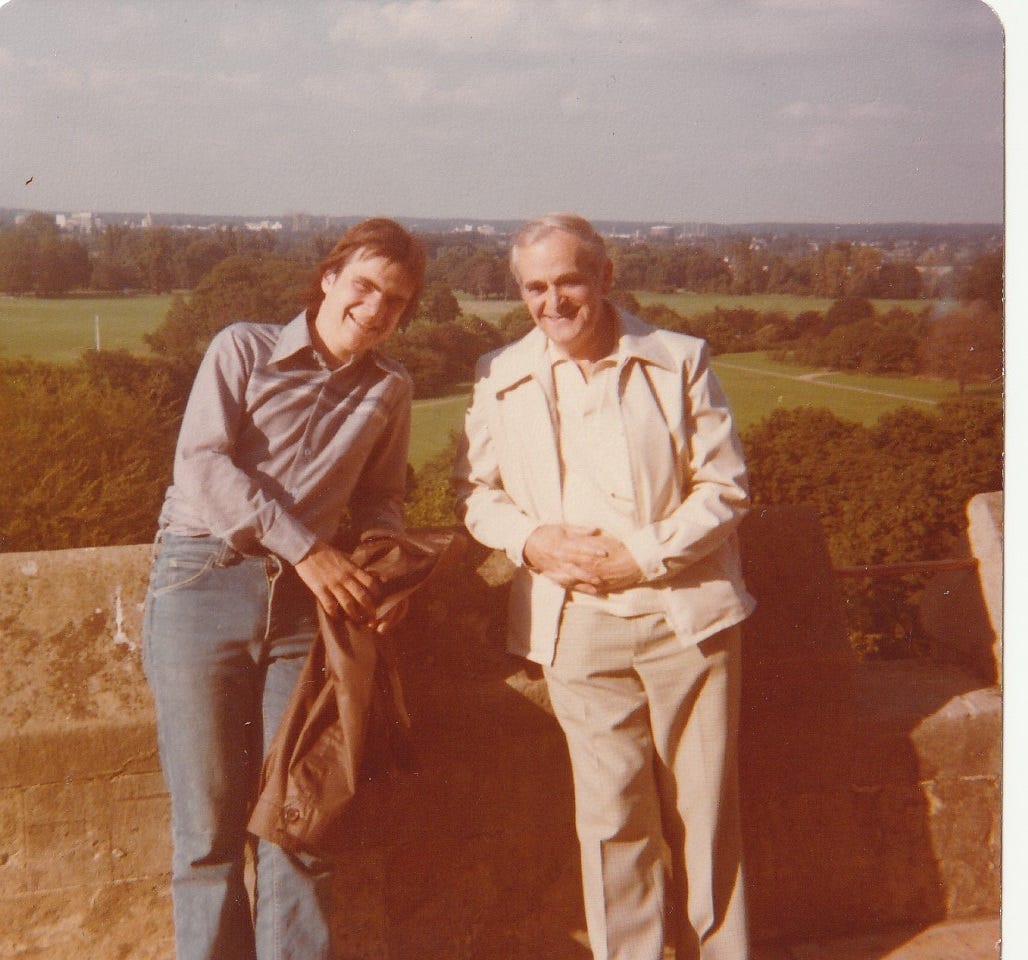

What you were as a man, a son, a husband, friend, father, and advocate erodes into forgetfulness, as each day, month, and year passes. You have become a still impenetrable image in a photograph that stares out from a mantelpiece onto an indifferent universe which you predicated in a book of yours.

If I lived another 50 years, in my heart and mind, it would be as if you only died the day before last. But to everyone else, and that is understandable, you are a past tense.

Your publisher doesn't even think you are worth the bother despite the world being like it was in the 1930s.

The other day, he messaged me to say, “The world has moved on, from Harry.” Why you should be forgotten in times like these baffles me. We are in such deep shit from this plague, from economic inequality and a growing march of fascism which tramples across nation after nation. It is an era of the Black Shirt and Brown Shirt redux.

Surely, this should be a time when progressive politics, journalism and trade unionism endeavour to emulate your generation’s fight against Hitler which transferred the West into a Welfare State for the many rather than the few.

Since you died, the apartment we once shared has been silent. No one visits and no one can visit, because the world went still from Covid after you expired from existence. In this apartment, I feel like a museum curator, because there are more mementos of your life than mine within its confines.

Your presence, your personality, and your temporal mark on what your life was about are everywhere. Pictures of Mum from the vacations you took together in Hawaii, Venezuela and Jamaica sit in ornate frames above the television cabinet. Your beloved oriental carpets adorn the floor. The antique samovar, that you rescued from the catacombs of Toronto’s Eaton’s department store when you were employed there in the 1960s sits on the table near where I write and maintain your social media profile. My brother Pete’s paintings, from his early years as an artist, still hang on these walls, including his rendition of Velazquez’s The Water Seller of Seville, which he did for a class at the Ontario College of Art.

He hated that painting and tried to throw it out dissatisfied by his inability to make a replica of the work. But you saved it. You marvelled at Peter’s determination to become an artist. “It takes courage to create.” To my regret when I was younger, sometimes I was jealous of your relationship with Peter. It felt like you praised him more than me.

It probably wasn’t so. But my skin was thin. I was the youngest in the family and lacked confidence. I wanted to move to my own tempo, I didn’t know how to dance to it with any grace when young.

I possess so few souvenirs to mark my six decades of living. It is not like I measured out my time with Prufrock coffee spoons. I didn’t want any reminders of my navigation across the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century.

I took the opinions, and the shit-talking of friends, family, and employers too much to heart. They saw the choices I made and the paths I took as fuck ups that they commented on over dinner as the “what’s he up to again,” storyline. On the surface, they thought I was like them. But I wasn’t. I desired something intangible. It's the rush of feeling deep and living large. Often, I tried to hide this from everyone because that is what our family did with frequent regularity repress and then express ourselves in passive-aggressive tones because we weren’t happy at being formed and fitted into roles not suited for us.

When young I pretended to be like everyone else who pursued or wanted to maintain their middle-class stature. I envied those who possessed the singularity of ordinary desires. They knew what they were searching for and that was to be able to afford the pleasures of consumerism. Friends sanctimoniously advised me “To get my house in order.”

To them, I was in danger of never reaching middle-class nirvana where one could afford every year a 10-day, all-inclusive Dominican Island sun vacation. To them, a perfect accounting for a life well lived was to own a house giving them a sense of prosperity.

In that house they ensure, through consumer purchases of mass-marketed goods, their family had a carbon copy life experience that equalled or was slightly bettered their neighbours. Everything clothing, furniture, sports played, sports watched, music enjoyed, and booze drunk had to be essentially the same from household to household. Regimentation was encouraged and diversity of opinion was only allowed when it came to Consumer Brands where some were Coke people and others Pepsi.

The only desirable difference people craved- was to have just a little more money than their peers. It allowed them to privately boast about having more gumption than the rest.

All this time alive and I can count on one hand the things that are mine exclusively. There is that maple wood desk that you and mum bought me, for Christmas in 1973 because I fancied myself older than my years. I still have the riding crop; my godmother gave me as a present when I was eleven. It was for my horseback riding lessons. Mum enrolled me in them because I wasn’t particularly good or interested in group sports.

She registered me in a horse-riding school because “A boy must be engaged in physical activity, to learn how to socialise.” It unsettled her that I was prone to enjoying my company rather than others. Despite being a solitary character, like you, I still hold onto photos taken long ago of me with friends or even past lovers that are framed and on display.

I have my yearbooks from the high school I attended in Scarborough, as well as one from the small private school I went to for my final year. That academy was in downtown Toronto’s Annex neighbourhood. You and Mum sent me there to improve my chances of success in the working world, as I had been diagnosed with a subtle form of dyslexia. Public schools at the end of the 1970s weren’t receptive to assisting those with learning disabilities.

I was nervous when I arrived at that school, as I was the new boy. I didn’t know what I would expect there because none of the students came from our social class in suburban Toronto. My fellow students came from wealthy families who lived in Rosedale and the other more affluent neighbourhoods of downtown Toronto. I was a fish out of water. It wasn’t just our social position that made sure I didn’t fit well at this school, I also looked twenty-five rather than my age of fifteen, because I lost my hair young and had grown a beard to compensate. So, when the other students first saw me chain-smoking at the school’s entrance, they thought I was a new teacher rather than one of them.

I know it must have troubled you to see me go to a school for toffs. But you did it because you thought it best, for me. Neither you nor mum had a guide from your troubled youth to indicate what was the right path to put your children on in the changing 20th-century world. You just figured it out as you went along and hoped for the best.

I was only sixteen when I graduated from that private academy. But I felt the pressure of our family’s history of struggle and toil when mum said, “You must go to university next year,” at my graduation lunch held in a trendy Yorkville, restaurant,

I knew I wasn’t ready for university. But considering the cost of my year at private school and that you and Mum were denied a formal education because of the Great Depression, I was obligated to become a university student as soon as possible.

I knew it was not the right time to go because I was too young both emotionally and chronologically. I wanted to improve my writing skills, which were hindered by my learning disability and made me misspell words or omit them altogether from a sentence. I needed small class lectures and individual attention, and that was not how universities worked in the 1980s.

Besides, life at home had become unpleasant for everyone. Our house was a toxic battleground because both my older brothers were going through personal difficulties that enveloped us, as they sought to medicate their disappointments or mental illness through drink, sarcasm, and anger. For me, it was a tough time to come of age as a teenager made awkward by premature baldness, lack of physical coordination and a learning disability.

Everyone in our family at that time was dealing with issues of their identity and lack of self-esteem, I didn’t recognise it, then....

..You didn’t know how to deal with it and how could you have considering; your early childhood would have made Charles Dickens weep. So, while our family self-emolliated itself in emotional chaos. You reverted to the factory default settings of your youth, where hunger and homelessness had taught you to work harder to provide more material goods to ease the suffering and hope the storm would pass. But it didn’t our family’s dysfunction grew as my brothers and me aged.

In that familial chaos, I started my first term of university, but, I didn’t have a map to guide me through the uncertainties of post-secondary education, because no one in our family had gone past high school.

You truly imagined when I went to university, it would be like your RAF induction during the Second World War. I’d go and be square bashed, find my niche, and four years later come home without even a scratch on my head. It did not happen that way.

Instead, my first term was a catastrophe beyond all fuck ups.

I am very pessimistic about the future, mine, yours, and society's. But there is optimism or perhaps stubbornness in getting up every morning, determined to finish the job I started with my father all those years ago. But I am not alone in that pursuit of trying to persevere and persist despite obstacles because all you are doing the same in your lives. But no question with less than 48 hours and few hundred dollars separating me from my rent a subscription or tip is greatly appreciated as well as needed. But only do it if it doesn’t leave you short because our struggles are equal. Take care, John