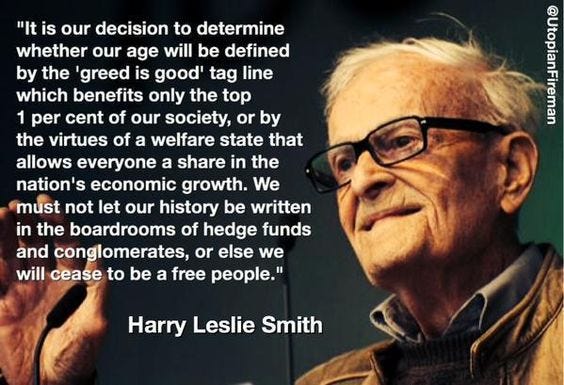

If the Working Classes built a Welfare State in the past, we can do it again. But to do it we must destroy neoliberal politics.

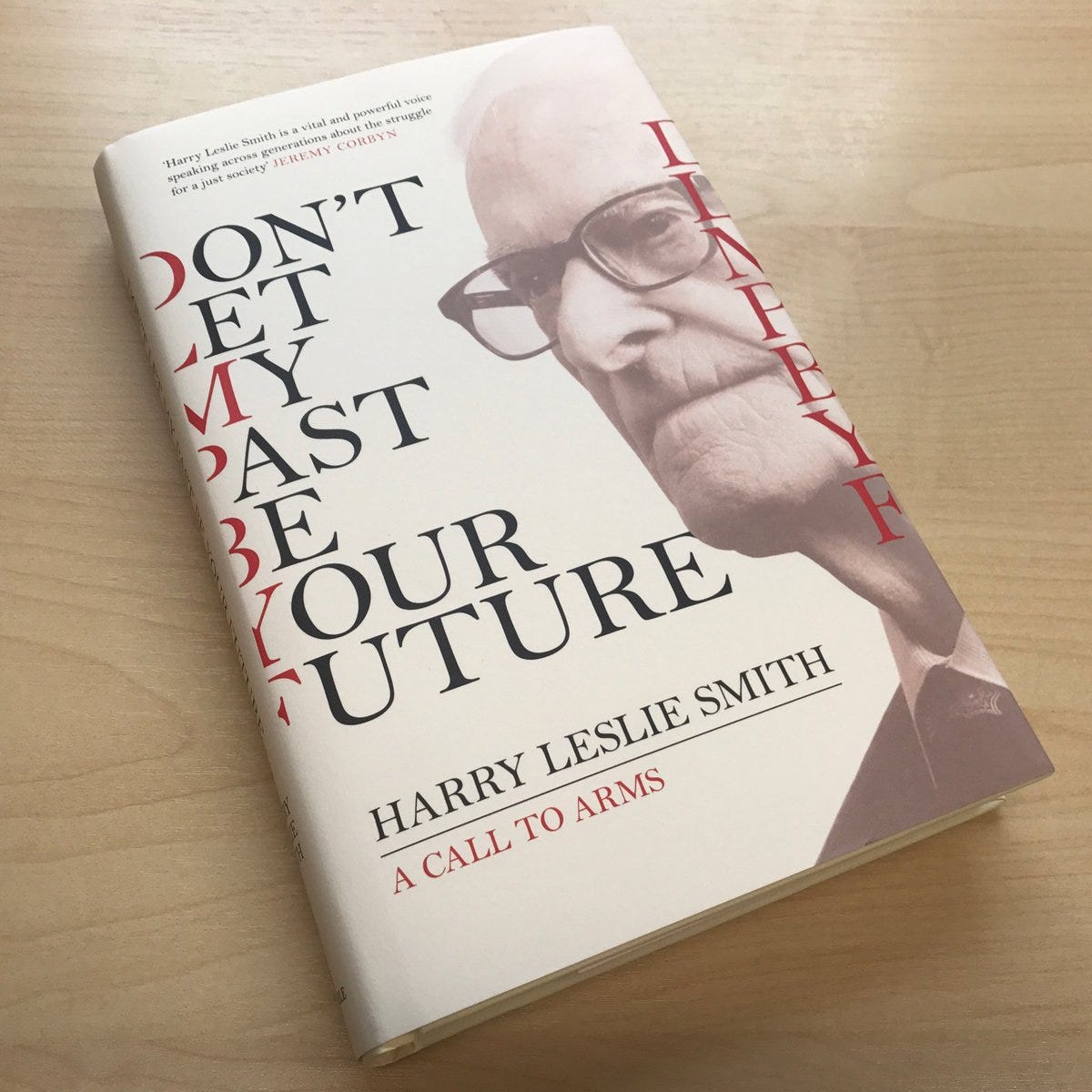

Works like Harry Leslie Smith’s The Green & Pleasant Land are more important now than ever now because we allowed the 1% to rewrite our history. If we don’t reclaim it they will own our future.

The Green & Pleasant Land tells a true story about the lives of working class people living during a time of political and economic extremities who from their suffering made a better world by constructing a Welfare State so that that all could share in a nation’s prosperity .

The Green & Pleasant Land is proof ordinary humanity can seize destiny and make a present that is fair to all. The Harry’s Last Stand project which I worked on with my Dad for the last 10 years of his life was an attempt to use his life story as a template to effect change. His unpublished history- The Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project. I have been working on it refining it and editing it to meet my dad’s wishes. It’s almost ready. This week I’ve been dropping the first 25k words of it. Today is the 4th part for your consideration.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going and me alive is greatly appreciated. So if you can please subscribe and if you can’t it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury. But always remember to share these posts far and wide.

Chapter Eleven:

During the last few weeks of Mum's pregnancy in September 1930, my parents harvested the bitter fruits of their failed marriage and served up a daily feast of their loathing for each other to my sister and me. In between berating my dad, Mum wrote desperate begging letters to O'Sullivan that were addressed to his last known residence down south.

My sister and I were charged with posting them. More often than not, Alberta would tear open the letter and read aloud Mum's pleas to her former lover to be a gentleman and take some responsibility for his child soon to be born. The ones that were posted were never answered.

Much later, Mum pretended they had been. My mother claimed she couldn't accept the ultimatum contained in his reply. O'Sullivan,

"wanted me to run off to Australia with him and our bairn, but I couldn't bear to leave you and your sister behind."

On the 24th of September, my mother went into labour. When the midwife arrived, Dad, Alberta and I were exiled to the kitchen where we listened to our mother's screams and curses to have the "Bugger born." While afternoon moved to evening, Dad sat stoned-faced on a stool that faced an empty stove and waited for O'Sullivan and Mum's baby to be born.

Dad only broke his silence once during that day. It was after he grew irritated with me when accidentally during horseplay I hit my sister. "Good men never hit women."

After hours of listening to my mother curse the midwife and the midwife curse my mother back, all of us- finally, heard the screams of a young life arriving into this world.

The midwife yelled for us to come and see the new addition to the family. Dad refused to leave his stool. But my sister and I went to our mother and marvelled at our baby brother.

My mother named him Matthew after his biological father, ensuring my dad rejected him outright.

Not long after Matt’s birth, our unhappy family did a midnight flit from Chesham Street because of rent arrears and ended up in another miserable slum called St Andrew's Villas. The new neighbourhood was fraught with itinerant labourers, unemployed mill workers, former soldiers from the Great War and struggling pensioners.

My parents paid a reduced rent under the agreement; we cleaned the common areas, including the outdoor privy, which stank as if it had been in use since the Doomsday Book.

As in Chesum Street, the other doss house neighbours were led to believe our dad was our granddad. It was a necessary deception in my mother's scheme to find another man to provide for us. My dad went along with it reluctantly. But I was shamed not by my dad's surrender to his debasement but by my own acceptance of it by calling my father "Grandad" in public.

St Andrew's Villa had a common room where I became acquainted with the other tenants. They were once all hard workers, but the Great Depression had ground them into factory floor waste. Some were accepting of their fate others angry. Mr Brown was one of the angry ones.

Brown had been a soldier in the Great War, and from morning to night, he was pissed off that the promised land fit for heroes had turned out to be bollocks. There were a few other veterans of World War One, who lived under our roof, and they looked to Brown for leadership and guidance. He knew what to say when shell shock overcame them. He went to their rooms when they screamed at night, "GAS, GAS,” or cried for a dead comrade blown to nothing from artillery.

Brown was a chain smoker and the brand he smoked advertised itself as World Famous. To prove it, inside each packet of cigarettes, they placed a national flag printed on a silk card from a country that sold their brand.

Each time, Brown opened a fresh packet of cigarettes he'd give me the silk card inside.

At bedtime, while my baby brother cried and my parents quarrelled; I'd stare at the flags on those silk cards and wonder what those countries looked like and whether kids were as poor there as I was in Bradford.

Chapter Twelve:

The first seven years of my life were equal parts calamity, mayhem and despair because capitalism is pitiless to its beasts of burden and their offspring.

It was a tumble of events as ferocious as a rock slide deep in the bowels of a colliery. My sister Marion died from TB in 1926. My dad became an invalid from a work injury in the pits in 1928 which made him unemployable. From then on we flitted from one rented doss house to the next one step ahead of the bailiffs.

It was all too, too much to take in and comprehend for a bairn starting out in life. Every day was a series of challenges that determined whether we had enough money to afford food and rent.

Six months shy of my eighth birthday, my mother explained to me I needed to accept some adult responsibilities because we were so destitute. The money I earned was to assist in keeping us fed and alive. There was an off-license up the street from our house looking for help. When I approached the owner behind the counter, he gave me a disdainful look. He was a man quicker to blame than praise, quicker to berate than compliment. But the owner was wise enough to know it was cheaper to hire a child than a hungry adult to do general clean-up. I worked for him five days a week, after school and did a half-day on Saturdays. I scrubbed floors and stacked shelves for tuppence and leering glares from the owner. I worked quietly and diligently. Apparently, I showed enough aptitude for my position that I received a promotion of sorts. The owner now wanted me to deliver crates of beer to local customers. I was underweight and my growth stunted for my age because of malnutrition. But I was made the captain of a steel-wheeled handcart, wide enough to fit three crates of beer containing nine, one half-pint bottles. I manoeuvred my wares up and down the narrow streets around St Andrew's Villas.

It was a great humiliation for my father to watch me return from work and place my wages into the family’s piggy bank. My tips, however, I hid from them. With those pennies, I bought sweets and chocolate that I shared with my sister.

From our new squat, school was now an hour away. There was now little time for lessons and homework with my part-time job pushing crates of beer and my chores around the rooming house. Exam time came in November. Rather than face both the verbal and physical beatings from failing my exams, I played truant.

I spent most of my days loitering in the city centre of Bradford. I walked myself to distraction. Generally, I was lost in a daydream. Sometimes, I met my father on the High Street in a similar state of truancy. Both of us wished we had not run into each other, spoiling our day-dreams. My father would fish into his trouser pocket and give me a penny.

“Be on your way lad. Make sure your Mam is none the wiser of our encounter.”

I then trundled off lost in a dream. My fantasies about pirates and treasure seemed far better than my present surroundings or what was awaiting me at home. After being absent from school for several weeks, the truant officer paid a visit to my mother one evening.

I told him I was not prepared for my tests. I preferred not to write them. The officer let me off with a warning. However, my lenient sentence had not been received by the nuns. With great delight, they set upon me with the cane. Once corporal punishment had ceased, the good sisters unleashed a verbal maelstrom regarding God’s vengeance on lying, deceitful boys.

On the odd Saturday afternoon, I treated Alberta and myself with my tip money and went to the movies. We watched a multitude of short films starring Laurel and Hardy, Charlie Chaplain, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd. For a few pence, my sister and I disappeared into a celluloid dream. At the Odeon, everything was funny, everything ended with a smile or a kiss. In the pictures, everything was different from our way of life and those who occupied our doss house.

The cinema was a place of refuge for a small boy like me. Movies and serials let me fantasize and drift away into a world filled with adventure and rewards. On the giant screen, life was indeed larger and everyone was beautiful. Sadness could be overcome and justice was always delivered.

But the furtive escapist dream melted like film against a cigarette when I got home to St Andrew’s Villas. One Saturday afternoon after a visit to the cinema, I went in to greet my mother sitting in the common room because I wanted to tell her about the film I had seen at the matinee.

My father sat in the corner, pipe in mouth, staring forlornly at a wall. My brother fed on her breast. Irritated by my entrance or my calls for attention, my mother pulled out her engorged breast from Matt’s wet lips and pumped her milk across my face. It ran down the sides of my cheeks and my mother laughed and said with contempt.

“He looked hungry too!”

I fled the common room enraged, ashamed to our room upstairs.

*********************************

There was little time for me to put two and two together and know that my dad by the autumn of 1930 was soon for the chop as part of our family. Dad was now a ghost that was rarely seen with us when out in company because he was now considered by others our Granddad. My mother's machinations to replace my dad with someone who could feed us were finally ready to be harvested when she ensnared Bill Moxon to her heart and bed.

Moxon was trouble for my family- the moment he took a room in the doss where we lived in St Andrew's Villas.

He was a cowman who worked on a dairy farm- located a few miles outside of Bradford.

My mother developed an affinity for Bill because he is young, tall, handsome and thick as a plank. Mum knew how to appeal to his vanity and pretend she was subservient to him. He was putty in my mother's hands and too dumb to know- he was being cast as the new breadwinner for our family.

No one in the doss gossiped about her affair with Bill because they were under the impression told to them by us that my dad was our grandfather.

In their minds, why shouldn't a "young widow," have a bit of comfort during these "troubling times."

My father, however, did know, and it humiliated him. After two years of enduring unemployment, homelessness, and seeing his children starve, my dad's last straw was being ordered by my mother to take lodgings in the doss house attic.

He asked why, and my mother said,

"Bill is moving in with me because you aren't a man anymore."

Mum also let my sister and I know we'd be sharing that damp, lightless attic with our father. According to my mother, it was to keep Dad company but it was because Bill couldn't stand children. If Moxon had his way, my brother Matt would have joined us. But he was still being breastfed, so stayed with them.

After my mum told my dad his fate. He walked away from my mother and went down to the common room to be alone.

After some time, my mother asked my sister and me to check on our father. We went to the common room, opened the door and found him sitting quietly on a chair with his pipe clenched between his teeth.

I called him. But he didn't answer.

Then- while standing at the top of the stairs, my mother called to him. She said that it was best he went to bed. Her voice triggered him, and a roar of outrage exploded from his mouth.

“I am betrayed; I am cheated.”

Dad charged up the stairs. He held a small knife in his hand used to clean his pipe. Its base was shaped like a miner's boot and that last memento from my father’s working life down in the pits. The blade would have had trouble causing a paper cut, let alone wounding someone. But at that moment, my Dad did want to physically hurt my mother and cut her for the thousands of wounds he thought he had endured as her husband. When he reached the top of the stairs, he lunged at my mother.

Mum easily overpowered my father and pushed him to the floor. Dad remained there for a long while and sobbed quietly, his anger spent.

The commotion stirred the other tenants, and their doors crept ajar.

The next morning, my mother sent me to the butcher to get two ounces of roast beef.

“For your father.”

At tea time, my father cut slivers of the meat and shared them with my sister and me while my mother fed Matt and tried to pretend that nothing had happened to our family.

Chapter Thirteen:

During those early years of my life, my dad's love for me was always plentiful. No matter how sparse materially our existence was during that long ago time of my boyhood, he attempted to bring cheer to all the gloom around us. Dad certainly didn't get as many glad tidings as he gave.

I will never be sure if he understood how loved he was by me. I have missed him during the many decades I have existed since poverty parted us. What a horrible and criminal waste it was for capitalism and our so-called British democracy to allow people like my dad to sink under the waves of penury. Those who were lost to the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression were like sailors who had fallen overboard a ship. Their cries for help were heard but no attempt at a rescue operation was ordered because they were considered non-essential cargo.

On Christmas morning, high above the flock mattress I shared with my sister- rain smudged the skylight window of the attic in the doss house. My body felt damp and cold underneath the coat I used as a blanket. Dad woke my sister and me with a greater-than-usual gentleness.

My father gave my sister and me each a penny candy wrapped in coloured paper. He served us weak, lukewarm tea, which he had made in the room my mother and Bill Moxon occupied below us. The tea was sweet from dollops of sugar. When I finished drinking it, I sucked on the penny candy whilst washing my face with a rag I dipped in a wash bowl of stale water.

My father instructed us to go and wish our mother a Happy Christmas. Which I reluctantly did because I was not looking forward to encountering Bill. He was only a few weeks into being part of my life as my mother's "pretend" husband. But Bill acted towards me as if he was there to smarten me up with stern discipline. He was always made worse by drink and I knew he'd had a stomach full on Christmas Eve.

I heard his drunken carousing because his songs, swearing, yelling, invectives, and jokes barged into the attic on the violent wings of his booming voice. I knew meeting him on Christmas morning, he'd be hungover, sullen and prone to sharpness against me.

Downstairs, I found my mother making a breakfast of fried bread that I washed down with another cup of tea. She had a present for both my sister and me that the Church had provided indigent mothers so that their children wouldn't believe Father Christmas had forgotten them.

My mum had enrolled my sister and me in the diocese festive charity meal. Before lunchtime, I left the doss with my sister and walked to the parish church to hear mass and receive the church’s bounty.

The feast for Bradford’s catholic poor was held in a gymnasium owned by the Saint Vincent De Paul Society. Inside, a nun gathered us in prayer. We who were destitute, hungry, poorly housed, and unlucky gave thanks to the ever-watchful Jesus.

I prayed that the nuns were in a forgiving mood that day. I did not want my ear pulled or my backside bruised by their love for discipline in the name of the Lord.

We sat on long bench tables and ate our Christmas meal. It consisted of stringy poultry, spuds, and pudding. The gravy was thin, and the food tasted of lost hope.

A priest with a tubercular cough wearing a dingy Father Christmas suit arrived after the meal. He presented each of us with an orange and a pair of socks. The priest was impatient and irritable with us because he enjoyed drinking more than ministering to children.

At home, I found my father upstairs in the attic. Frost was on the skylight that was streaked with coal soot.

“Happy Christmas, lad, sorry there weren’t much for thee and thy sister. Next year, hey son, next year…”

In the first week of 1931, my father moved out of the doss house and out of our lives. Dad left quietly without even a goodbye to me. He was gone as if he had never been in my life.

When I turned eight, I stopped asking my mum about my dad. He was alive, but I was told to think of him as dead because that was my mother's story, and she needed to tell that story to survive. Much later in my life, I understood to survive poverty; you must do unspeakable things. It turns you feral, or it makes you dead.

Chapter Fourteen:

During the first week of 1931, Dad moved out of the doss house. He left quietly, without fuss or fanfare. Dad patted me on the shoulder and told me to be a good lad. And with that, my father slipped the moorings of our family and vanished from my life. My father was the one who left but it was my mother who had deserted him. If the times had been kinder, the circumstances different, Mum would have not done what she did to my father. She wasn't a cruel woman but the Great Depression hardened her like it calcified us all.

Forcing my dad to move out and exiling him from his children was a brutal punishment for the sin of becoming disabled at work and because of it unemployable. Rewriting my dad's narrative to exclude him from fatherhood, and humiliating him by changing his stature to grandfather to the outside world because it allowed my mother to take up with another man was also a merciless punishment.

Still, it was Mum's only solution because- working-class divorce was precluded owing to its expense as well as society's sanctimony. I knew it was wrong that my dad was evicted from our lives, and denied his right to be called our dad.

I protested to my mum but not strongly enough. Alberta fought harder for our dad. But she was three years older than me. So being ten, Alberta knew Dad was as good as dead to us once gone from the doss we called home. Yet even Alberta gave up the fight for him. Like us all hunger and the fear of being sent to a workhouse overcame her loyalty to him as well.

The betrayal of our father allowed my sister and me to survive childhood during the dirty 30s. But it destroyed us as a family. It was a scar on our souls that didn't heal. It made us both love and loathe our mother in youth, middle age and old age because she implicated us in the destruction of our dad. It wasn't until she was long dead that I truly understood my mother's sacrifices to keep us alive and that she did not deserve my rancour over the harm caused to me when young.

With Dad gone; Bill Moxon became the central male figure in my childhood. Moxon was a man of quick temper, explosive rages and extreme intolerance. As human beings go, Moxon and my dad were polar opposites. My dad loved poetry, history and nature. He was a socialist and a kind man who believed in trade unionism as a path to a better society.

Moxon was barely literate and no socialist. My mother's new boyfriend was an angry man and I tried to stay well clear of him. Soon after my dad left, Bill lost his position as a cowman because he got into a fight with a foreman, over some real or imagined slight. To my mother's relief, Moxon quickly found another job. He was hired as a pig handler at a nearby farm.

In the mornings, Moxon travelled across Bradford with a horse-drawn cart. He collected slops from the restaurants and pubs for the pigs to dine on. On occasion, he brought home for Alberta and me a large formless mass of discarded toffee that was intended for the pigs to eat from the Mackintosh sweets factory.

With a hammer, Alberta and I chipped away at the mound of toffee that had bits of wax paper stuck to it. Eventually, our hard work transformed the mass, into shrouds of thick brown treacle. We sucked the sweetness from it as a carnivore licks the marrow from a bone.

Not only was Bill in charge of feeding the pigs, but he was also responsible for cleaning the styes of their shit.

Every day, he shovelled, washed, and scraped away the effluence of four hundred well-fed pigs. After his shift was done he rode the bus home stinking of shit. When he returned home, his stench enveloped the doss. But the other residents feared his temper. So in his company kept schtum about his foul odour.

One weekend, Bill needed me to give him a hand at the pig farm to do a "man's job," he said. Moxon was too ignorant to understand I'd been doing a man's job ever since my mum put me to work as a beer barrow boy for the off-license down the road from our doss house.

When we arrived at the farm, Bill explained he had come to kill a pig. I was required to assist him because the business was dodgy. But me helping him would mean Moxon would be allowed to take some of the slaughter home for our tea. I was terror-stricken. Blood-curling images danced in my head about having to slay a giant pig.

Bill had me wait in a shed while he dragged a pig from its stall over to its place of execution. In the distance, I heard a pig wailing in terror and Moxon cursing the animal's reluctance to be dragged by a rope to his appointment with death.

The shed had a tin roof, cement sides, and a stone floor. Across the back of the shed were two large steel rails. There was a hook with a rope attached to it. The hook rode the rails on a metal wheel attached to it. On the floor, there was a giant sledgehammer, which appeared to be the same height as me.

When Bill arrived at the shed, he yelled.

“I’m going to put this noose against pig’s mouth on top of teeth. Come quick, I need you to hold the rope as tight as you got. Piggy’s head has got to be high to the sky. Don’t let go of im, lad, because I am going to clout im, from behind with hammer.”

The pig struggled with every turn to break free. I was terrified that the pig would escape and attack me for threatening his life.

I stammered “I can’t do it, Bill. He’s too strong.”

“You better lad or you are our tea tonight.”

The pig cried out in fury and fear. Its back end dropped dollops of shit.

I grabbed the short rope and was now so close to the pig that I smelled its frightened breath while its giant tongue slapped back and forth against yellow threatening teeth.

“Higher, lad, higher.”

I felt I could not hold on for much longer.

Finally, Bill smashed the back of the pig’s head with the sledgehammer, with an executioner’s strength, and the pig collapsed.

Bill slit the throat of the pig with a long knife blade which caused blood to explode from its jugular. I was sick to my stomach and rushed away to retch.

Moxon hoisted the pig up onto the rail trolley to let the blood run clean of the carcass. Moxon butchered the pig, and we took home a small portion of meat for a Sunday roast.

When the Sunday meal was being prepared, I didn't think of the pig, its fear and brutal death. I only thought about how I was always hungry and missed having the sensation of a full belly and the feeling of safety that brings.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John

What a hell of a life 😔

Every time I read those stories, I get a horrible feeling for children. It's odd, because I didn't grow up that way, horribly poor. Honestly not knowing where their next meal was coming from, or if they'd live to see it. Children still live that way. They swim rivers and scale walls to find a better life. We let the capitalists drown them with their mothers and fathers, knock them off the walls we spend billions to build. Why can't we feed the families untill their fathers get jobs butchering our livestock and their mothers raise our children

God have mercy on us.