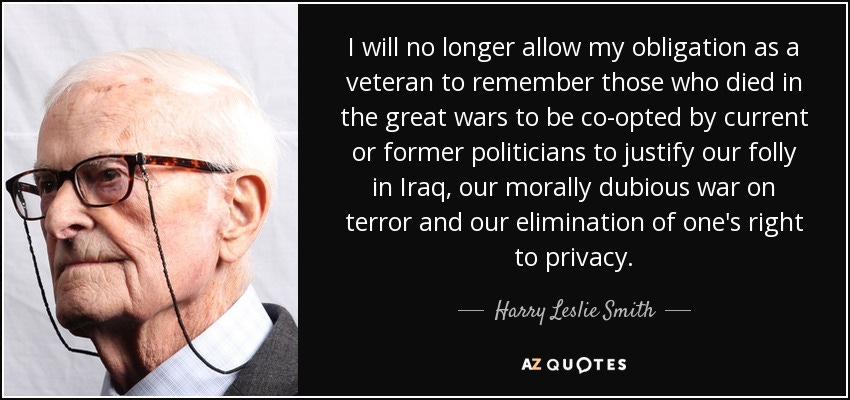

In 1936 the working classes knew a war against fascism was only a matter of time. In 2024, we should understand this too for our times.

Harry Leslie Smith’s The Green & Pleasant Land tells a true story about the lives of working class people who lived during a time of political and economic extremities. From their sufferings these unemployed miners, mill workers, along with the rest of ordinary Britain made a better world for themselves and others by constructing a Welfare State, where all could share in a nation’s prosperity.

The Harry’s Last Stand project which I worked on with my Dad for the last 10 years of his life was an attempt to use his life story as a template to effect change. His unpublished history- The Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project. I have been working on it, refining it and editing it to meet my dad’s wishes. It should be ready for a publisher in May.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going and me alive is greatly appreciated. I depend on your subscriptions to keep the lights on and me housed. So if you can please subscribe and if you can’t it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury. But always remember to share these posts far and wide. Below is a chapter selection that deals with the rise of Hitler as Harry becomes a teenager.

Chapter twenty-two:

Bill Moxon returned to our household after months of being on the lamb from his responsibilities to the son he conceived with my mother. I don't know what possessed him to come back. He just came back and pretended as if he had never been gone.

Bill greeted me when I first saw him after his absence by singing a song he'd learned in the Royal Marines about how sailors better beware of the deep dark sea.

With Bill's return, so came his drinking, his yelling and his penchant for domestic violence. He was an unhappy man who intended to make everyone near him as unhappy as him.

Bill's routine of drinking and brawling with my mother ensured I stayed away from our house unless it was for a meal or to kip down.

When I wasn't at work, school or finding books to read at the library, I began to attend meetings at the local Mechanic's Institute, where journalists, writers and advocates gave lectures on the rights of workers, domestic politics and the disintegration of democracy on the European continent.

I was twelve when I started attending these lectures, but I didn't feel out of place. These talks were filled with working-class folk, all with dirt underneath their fingernails, who desired to learn more about the causes of their poverty and oppression. There were cups of tea and comradery, in those rooms that were thick with tobacco smoke.

People went to these lectures hoping to find insight into how things could be made- better for themselves and fellow travellers who walked through the misery of the Great Depression.

I felt welcomed at these talks but also woefully ignorant. My education was interrupted so often by poverty that I didn't understand much from these discussions except that storm clouds of war and totalitarianism were approaching.

By 1936, the warnings against Hitler and Mussolini were available to anyone who chose to listen to them. Much of the middle class didn't because they were too busy enjoying their creature comforts. Their conservative politics didn't allow them to see Hitler as anything more than a politician for good governance.

The working classes knew that the tectonic plates of alternate ideologies were converging towards war because trade unions had heard from their sisters and brothers in Germany about the repression of socialists, workers and the persecution of Jewish citizens.

Even Bill understood early on "That Hitler is going to put us in the shit," which he exclaimed once to me after he returned from the outdoor bog with a tatty Daily Mirror under his arm.

At the age of thirteen, I became aware of Mussolini's genocidal attack against Ethiopia because they were widely reported in the newspapers and in the news reels. I hated the dictator and had enormous empathy for the Ethiopian people who were slaughtered or enslaved by fascist Italy.

The signs were all there that war was coming again for the young and innocent. It was coming to snatch and drag them to the underworld of death. It was only a matter of time despite Newspapers like the Daily Mail poisoning the minds of British readers with overt antisemitism and support of Hitler's fascism.

Things were changing, and war was brewing. A new order had taken root in Europe and Britain was incapable of responding to it because its own ruling classes had an affinity for them. Anyone with a modicum of self-reflection in 1936 understood that the times we lived in were uncertain. Everything was changing.

On the day the King died that year, my school announced his passing to the pupils and staff in assembly At it there were prayers and respectful silence while some teachers even cried.

But, that evening- I and other kids- paraded down the streets and sang at the top of our voices, "God save our gracious King, God save our Noble King. Send him to heaven in a corned beef tin." Old worlds were dying, and new ones were being born.

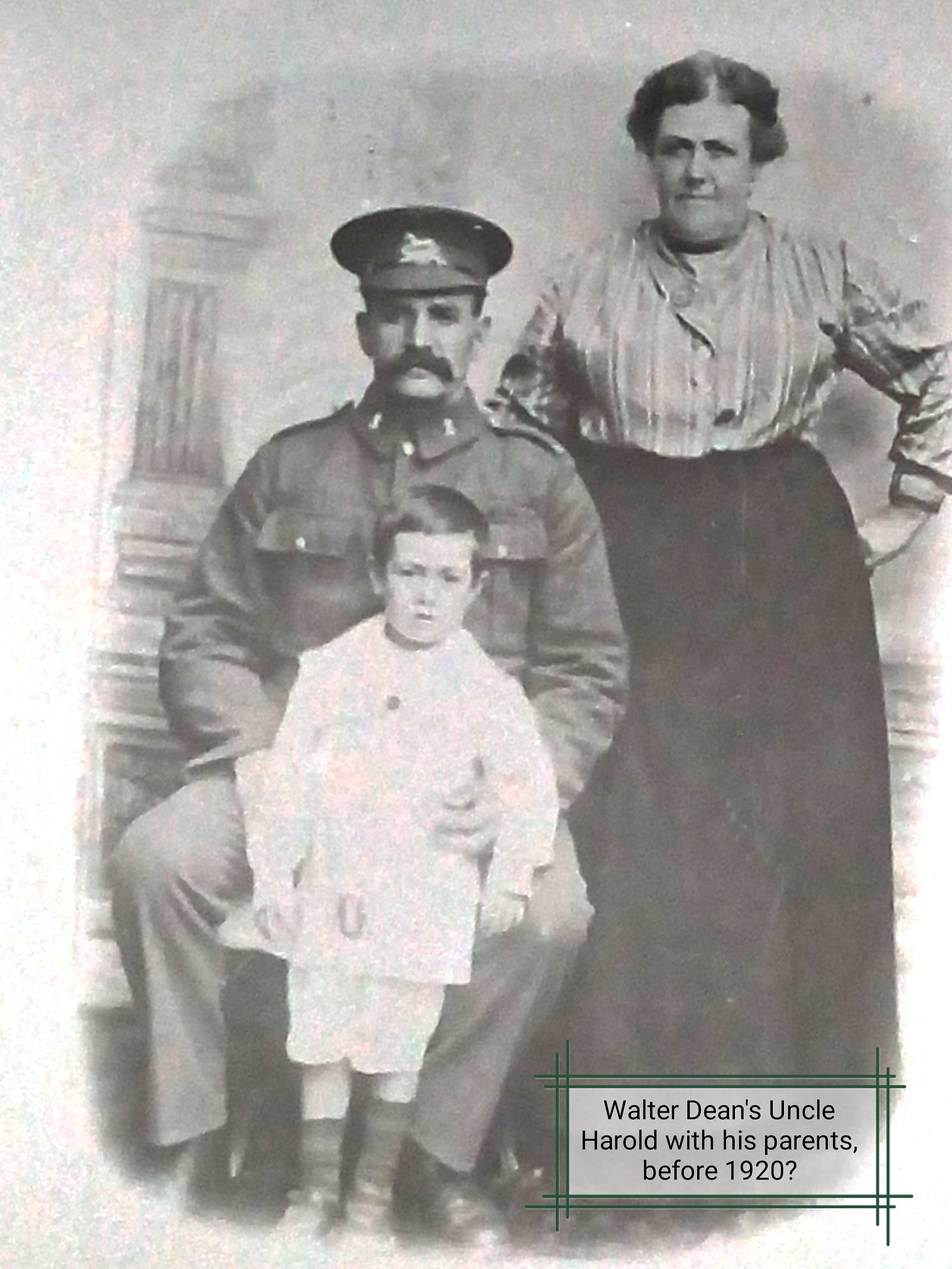

My grandfather died that year too, but he was not sent to heaven in a corn beef tin.

Grandad didn't die like the King- attended by doctors and servants while waiting for death in the comfort of a warm bed. My granddad died in immense pain from an intestinal cancer that ate away at his stomach with the ferociousness of wolves tearing apart a trapped deer. I saw him before he died because my mother forced me to.

The last time I laid eyes on him, I was seven. It was when I was sent to stay with my grandparents because my mother was in her final weeks pregnancy, with Matt, the child produced from her love affair with the Irish navvy.

Cancer had changed my grandfather considerably since I last saw him. He didn't look as I remembered him as someone who got his grub before all others in the family were allowed a share of the evening meal.

He lay on a cot that sat in the middle of my grandparent's parlour because he couldn't walk up the stairs to his own bedroom. There was a strong smell of bodily waste and sweat in the room. Underneath a sheet, my granddad lay- shrunken, defenceless and in agony. My grandfather didn't speak to me when I said hello to him. All his strength was reserved for cursing his pain and death coming to take him.

One of my uncles said they were waiting for morphine that they paid for with a whip around at the miner's hall.

"It'll send him off without the fuss."

Afterwards, my grandmother fetched me a Tizer's pop from the cold cellar wearing petticoats- as if she was still living during the reign of Queen Victoria.

When Grandad died, my mother went to his funeral, naturally without Bill. However, that didn't stop my grandmother from calling her an adulterer when they said hello to each other. My sister and I didn't attend our grandfather's funeral because we couldn't afford to lose a day's pay.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. It’s an SOS because the end of the month approaches and I am short on rent with only six days to go. I have discounted subscriptions as well if you subscribe through this post. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. A yearly subscriptions will cover much of next month’s rent. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John.