In 2024 we stepped through the looking glass into fascism. Only emulating how The Greatest Generation built democracies for the many and not the few will save us from annihilation.

Hi everyone:

For the last 6 months, I have been dropping chapter selections from my dad's unpublished work The Green & Pleasant Land. My edits on it have another 2 months to go before it will be ready for publication. The first 25 thousand words are finished -at least finished enough I feel confident to show you them. I wanted to drop the first 25k words of the manuscript as one post on Substack, but it is technically not possible. Instead, I will drop 5k words each day this week because it will give you a better understanding of the scope of the manuscript. Works like the Green & Pleasant Land are more important now than ever now because people have forgotten their working class past. In 2024 we stepped through the looking glass into fascism. What we are living now will only get worse and it will take more than a generation to change. It will take the grit and the outrage that past generations had who fought to take their lives back from being owned by the entitled.

That the West allowed the creation of the Welfare State a revolution greater than the French, American or Russian revolutions combined to be pissed away in an orgy of debt-driven consumerism and neoliberalism is probably the greatest proof that our civilisation is at the end of its days. But that is another book waiting to be written..

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going and me alive is greatly appreciated. So if you can please subscribe and if you can’t it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury.

Comrades, go well into Harry Leslie Smith’s Green & Pleasant Land.

Gentle Reader:

Death approaches me with actuarial punctuality because I am eighty-seven years old. My body is weary from decades of existence. I was not cheated in my dance to the music of time because I was loved and gave love in return. My life’s journey was a wonderful adventure that despite its early sorrows was filled with an abundance of joy and experiences that allowed me to become a better human being.

In my childhood and youth, I intimately knew hunger, poverty, sickness, and grief as well as the horrors of World War. How could I not? I was born to a working-class family at the crux of early twentieth-century history when the Welfare State did not exist. But at the age of 22 in 1945 I assisted in its birth in Britain. I was one of those people who grabbed destiny by the shirt collar and elected our nation’s first socialist government-Labour under Clem Attlee. The story of my early life that I am about to tell you is a history of me, my family and the struggles all people not born to wealth endured until the Welfare State was created in 1945. Then out of the ashes of the Great Depression and the rubble of the Second World War a society for the many rather than the few was born.

Chapter One:

I came to be on February 25, 1923, during a harsh and hungry winter for Yorkshire’s working classes. I was born on a night when freezing rain lashed hard against the windows of my parents’ slum dwelling located on the outskirts of Barnsley. Had it been up to me, I would not have picked the era or the economic circumstances for my arrival into life. Being born to poor folk at the start of the 20th century guaranteed a life with more tragedy than joy.

My mother laboured long with my birth. I would not be coaxed out with either gentle words or harsh curses from either my Mum or the midwife with a love of gin and cigarettes who assisted in my arrival. When I eventually did come into the world, I let all around me know I wasn’t pleased. I hollered and mewled like a runt of the litter for milk from my Mum’s breast because I was underweight. Being born malnourished was normal for my class in 1923. My dad earned his grub as a miner, and like all workers then, no matter how hard they laboured never had enough money to pay the rent and feed their families. We were capitalism’s beasts of burden and treated accordingly.

Working at the coal face is what my folk had done for generations. It’s all they knew, which is why even before the Industrial Revolution, my people were miners, except then it wasn’t coal we dug but tin. I am sure, in ancient times, my ancestors dug for the metals that were smelted into bronze. For hundreds of years, my family’s labourers and the millions like us made the entitled wealthy and us their humble servants. Had my working-class world not been changed by the Great Depression, I too would have kept hearth and home by hacking coal in its rich seams of Yorkshire like all my kind through our recorded history.

In the year of my birth, my parents were new settlers to Barnsley. They had come to this spot of Yorkshire because the pits here promised a better wage than up in Wakefield or Barley Hole. Besides Barnsley was far enough away from my dad’s siblings, who despised my mother- a woman who rubbed many in her world the wrong way.

In my teenage years, Mum soured by the hunger created by the Great Depression, revealed to me my father’s family were more than just colliers without brass or influence. They were “better folk” according to her, but my father had let his family’s legacy a pub slip through his hands. “It could have kept us in clover until we all breathed our last.”

On the day of my birth, my father was not glad-handed down at his local by neighbours in our village of Hoyland Common. No one slapped his back or shook his hand in congratulations because; when I was born, Dad was in his late fifties, and Mum was twenty-seven years his junior. She had foolishly fallen in love with him in 1913. He had the gift of the gab and an optimism that was infectious.

My mother attached her wagon to my Dad's destiny ten years before my birth because she believed, despite his advanced age; he could guarantee her a secure future. Mum lived until the day of her death feeling cursed by the creed: marry in haste and repent in leisure.

She had been beguiled by his prospects because his father was the innkeeper of a public house that stood on the fringe of a colliery in the decrepit village of Barley Hole, found in the nether regions between Sheffield and Barnsley. My parents married on the expectation he’d inherit the pub upon the death of my granddad. Life always has other plans for us rather than happiness and a pocket full of cash. My parents’ dreams for financial stability were as hopeful as believing a sandcastle would stand after the eventide came ashore

My father didn’t inherit the publican license after Granddad died in 1914. Instead, it transferred over to his uncle Larrat ensuring Dad would die a miner rather than a business owner. The machinations Larrat employed to do this were as pernicious and preposterous as any subplot from a Dicken’s novel or at least that is how it seemed to me when my mother during the 1930s ranted about our “lost legacy.”

After my grandad died my parents moved on from Barley Hole with few possessions except a portrait of granddad and an upright piano that was once played by Dad to entertain off-shift miners with seaside songs from Blackpool.

According to Mum, bad luck followed our family with the persistence of a stray dog looking for an owner because of Dad’s tender heart. He wasn’t “rough and ready,” even after decades at the coal face. Poor Dad was the toughest of us all because he took the misfortunes to come in the years after my birth with stoicism and good humour. It is a pity none of his family recognised it until he was dead and buried in a pauper’s pit because we were too busy trying to escape our own destruction.

Nine years passed between my parent’s marriage and my wails of life. The intervening time was a series of disappointments and defeats for them. By 1923, their relationship was shorn of its lustre. Mum was only twenty-eight, but she felt like a broad mare when I was born having already given birth to my two elder sisters, Marion in 1915 and Alberta in 1920. Whereas Dad was fifty-six and his physical strength was in decline. His ability to earn a living and us out of the poor house was in jeopardy.

The worry, the daily struggle to stretch Dad’s impecunious wages to both make the rent and put food on the table had by the time of my birth worn my mother down to a nub of anger, outrage and cunning that she hoped would outwit whatever calamity was intent on knocking on our front door demanding entry. Mum’s acerbic vigilance was understandable because she was in constant war against rent collectors, shopkeepers who denied her credit, and in a daily battle with the grim reaper that wanted to snatch my eldest sister Marion to live with him in the dominion of death.

By the time of my birth, my sister was gravely ill with spinal tuberculosis. TB terrified my mother because her older brother Eddie died from it in 1918 after doing a stint in the Veterinary Corps in France during the Great War. Mum knew long life did not await Marion. But my mother would do everything to forestall my sister’s early reservation with death. But a mother's love for her child isn't a currency that can be exchanged for proper healthcare in a society designed to make a profit for the few.

Chapter Two:

I shouldn’t have survived my childhood during the 1920s because I was sick more often than well. Working-class children were easy prey for death in the early 20th century because healthcare was allotted to those who could afford it- which were the middle and upper classes.

I was lucky I made it through my first two years of life because my belly was more times empty than full. Too often, persistent malnutrition came close to killing me were it not for my mother’s stubborn determination to see me live into adulthood.

It was she who kept the fire of life burning inside of me no matter how ill I became as a bairn. At around 18 months, I developed a prolapsed rectum from malnutrition that caused a part of my intestines to slip out of my backside. Later in life, when I questioned her erratic mothering skills, Mum roared back at me, “ You wouldn’t have been alive today if I hadn’t shoved your bowels back up your arsehole when you were a sickly lad. I told death to bugger off and you now thank me like this?”

To her lasting regret, Mum was not able to say the same to Marion in adulthood because she didn't survive her childhood. Marion couldn’t be fixed like I was by shoving my guts back into me. TB wasn’t cured by brute force, and for Marion to survive her form of TB, she needed care in a sanatorium- and that was beyond my parent’s fiscal resources.

1926 was a horrible, hungry time to be dying if you were working class. The streets where the working class lived were angry because they had been cheated by their political leaders who promised a "Land fit for Heroes," after the Great War in 1918. But eight years on, wages for miners hadn't gone up but instead were clawed back. Other workers felt a similar pinch from their employers who wanted more hours worked for less pay.

By May 1926, the working class could take no more. In solidarity with the miners, who were fighting the coal barons for better pay and conditions, Britain's trade unions called for a General Strike to settle wage demands and working conditions for all workers.

The General Strike terrified Britain’s establishment because they feared the country was about to fall into a rabbit hole of revolution. It didn’t want to see Britain’s Green and Pleasant Land for the entitled classes become Central Europe in 1918- where riot and rebellion by the proletariat swept away the ancient rule of aristocracy.

During the General Strike, Winston Churchill made speeches in parliament about the strikers and portrayed them as communist revolutionaries out to topple democracy. Strikers were described in newspapers as if they were insurgents or a rabble mob that wanted to storm Buckingham Palace. The prose was feverish and by inference reminded readers how Russian revolutionaries had stormed Imperial Russia’s Winter Palace in 1917, overturning that monarchy.

Right-wing newspapers turned working-class aspirations for fair wages, affordable housing, and the right to time off into a communist plot by Lenin to make the United Kingdom another Soviet Union. Naturally, the middle class accepted this propaganda as gospel because the worker was not thought of as human on equal footing with a homeowner. To them, we were a different and inferior species whose purpose of- existence was to be their housekeepers, dig their coal or drive their commuter buses to their comfortable white-collar places of employment. We were background players in their lives, extras in their real-life silent picture extravaganza.

The General Strike began with militant optimism, and in less than a fortnight; it was crushed by the government, its press, and middle-class animosity. Only the miners’ union refused to budge or break in the face of the intimidation thrown at them by the government and the press. While other workers returned to their employment, the miners’ union held firm with the slogan “Not a penny off the pay, not a minute off the day.”

It was heroic but in vain that the miners’ held their picket line after other trade unions had been beaten into surrender. For their fight for better pay, the miners, their families, and the communities they lived in were destroyed and starved into submission by the Coal Barons who refused to negotiate with the miner's union. The Coal Barons had a stockpile of coal and compliant miners who were not union members to supply Britain’s economy with the fuel it needed to keep running for as long as the strike continued. They had time on their side whilst the strikers did not because strike pay did not pay the rent or the food bill.

During the strike, miners having no wages went into deep rent arrears and many were evicted from their housing. They were starved into submission and then into surrender like rebels on the losing side of a civil war. My mother was compelled as other women married to miners to take my sisters and me to soup kitchens for our daily meals because there was no money left to pay for groceries.

As the strike dragged on for months, Marion's TB grew worse because of our limited food supply. Death was coming for her. My father and mother knew she'd soon be dead. It's why I was told, “Play near Marion because she won’t be with us for long.”

Marion died by inches at the beginning of 1926 and then by feet when autumn approached. The TB wrapped around her spine like an Anaconda and then spread to her other organs. She lost both the ability to walk and speak. To ease my parents’ burden of care, Dad’s trade union donated to them a wicker landau. It had thin rubber wheels on it, which allowed Marion to be taken outside to enjoy Barnsley’s infrequent days of sun that weren’t obscured from coal fire pollution. When Mum pushed Marion down the street with me by her side, I’d watch the wheels turn and hear their mournful squeak that sounded like cries of pity for its rider above.

Most often, Marion's time before death was spent marooned in our dingy “couldn’t swing a cat” parlour imprisoned on her landau. Sometimes, I sat on the floor near Marion and told her nonsense stories that she responded to with groans of pain or thrashing her hands against the side of the landau. For eating, bathing, dressing, and going to the bathroom, Marion was now totally dependent on my mother’s care. It exhausted my mother and made her impatient with others, including me because I was underfoot when Mum needed to give all her attention to my dying sister.

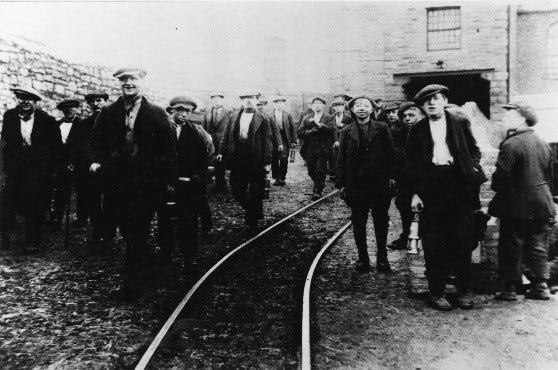

In early autumn, the miners' determination to continue the strike began to die. The coal barons had starved them out and broken them without mercy. Just before the strike ended- my dad took me to one of their pickets. I don't know the reason; it might have been as simple as there was no one to care for me because my mother was busy tending to Marion. Or it might have been something more profound like my father- wanting to imprint me with an image of working-class courage in the face of insurmountable oppression. Whatever the reason, I remember my visit to his picket line as a lesson taught to me. All human beings must have the right to a decent, fulfilling life.

At the picket, Dad let me ride on his shoulders while he stood with his comrades to fight for fair wages and better working conditions. On Dad’s shoulders, I felt happy and safe in the company of him and his mates who fought a fair fight for our kind.

Not long after my trip to the picket line and my triumphant ride on my father’s shoulders, the miners’ union settled with the Coal Barons. They surrendered to the owners of the pits as if they were a defeated army and were treated with no more mercy than Germany was during the drafting of the Versailles Treaty.

When miners returned to work in the pits, their work hours increased to Victorian times whilst their wages were cut in half. The General Strike proved to the working class that Britain had sacrificed its young in the Great War for nothing more than to maintain and perpetuate the wealth of the few families who controlled our nation’s economy.

October 1926 was a month of incredible brutality: Marion was dying, my family was starving, and the miners' general strike collapsed in humiliating surrender. It was feudalistic what happened to my family and our mining community that year. We were just meat for capitalism’s economic grinder.

At the beginning of October, Mum knew she couldn’t care for Marion any longer. Death was coming hard and quick for my sister. There was nothing left to be done for her at home, and since my parents didn’t have middle-class wealth, Marion couldn’t be taken into the care of a hospital that charged for health services. There was no alternative for Marion’s end-of-life care. She had to be committed to our local workhouse because it had a small infirmary where the working class and the indigent were provided with limited healthcare services. Generally, it was only laudanum to make one's end of life less torturous.

One morning in early October, Dad, with the help of a neighbour, lifted Marion, who rested on her wicker bed onto the back of a coal wagon drawn by a lone horse. After Marion was put on the wagon, my mother climbed up to go with her to the workhouse. The horse and wagon forlornly pulled away from our front stoop and moved slowly down the street towards the workhouse.

Marion lasted less than a fortnight in the workhouse infirmary. My parents went every day to visit my sister and make her feel that she was loved until she died.

There was no funeral for Marion after she died. My parents could not afford the cost of a burial because they were destitute from fighting the General Strike. Instead, she was dumped in a pauper's pit and shared her grave with the other indigents of our community who died before their time from lack of affordable healthcare.

It was bitterly ironic that the month and year Marion died was the same month and year A. A. Milne’s first Winnie the Pooh book was published and sold in shops. Marion was dead, and the General Strike was crushed by the entitled. But for middle-class kids at the end of 1926, their bedtime stories were filled with tales about "Pooh Corner- an idealistic wood that was easy for them to imagine because they weren't hungry, cold, or their families too poor to afford a doctor should they fall ill.

Chapter Three

Grief took lodgings in our house after Marion died- and it was not stoic or solemn. It was bitter as tea made with vinegar. Rage steeped in my mother's heart over my sister's death. Mum knew and spoke aloud what Dad kept to himself. "She was snatched from us because we are poor."

No one was able to console my mother during those first weeks of mourning, least of all her husband.

Dad seemed to my mum too tepid in his hurt over Marion's passing. He didn't wear the emotional accoutrements of mourning. Dad didn't weep or howl because grief had punctured his spirit and deflated his heart. Mum thought my father's reluctance to display emotion over Marion's death was as good as him tugging his forelock at death like a servant to its master.

Mum was being unfair because Dad wasn't lukewarm in his sorrow over Marion's death. He was hot with shame over it. Dad's grief was silent and rheumatic with self-recrimination as he blamed himself for Marion's spiral into death.

My Dad realised hunger induced by being in the General Strike was a factor in Marion's death from TB. He was the family's breadwinner who failed to put food on our table because the General Strike brought famine to our community and every other mining community across the land.

My sister and I were too young to grieve for Marion. She was here and then gone. To where I did not know? Marion was just absent from our home. She was gone and, in her place, sadness sat and brooded in our home.

During daylight, my sister and I escaped the harsh sorrow our mother wore by traipsing around the streets of Barnsley. We fell in with other children at play or visited our grandparents who lived close by. For days, I'd lose myself in imaginary treasure hunts with Alberta at a nearby rubbish tip. It was a place strewn with debris from the lives of the working poor: rotting clothes, broken crockery as well as busted furniture heaped in ziggurats.

We scavenged like Howard Carter for Tutankhamun's tomb, looking for loot that we told ourselves was buried underneath the dead ground that only gave up brass buttons from the 19th century.

Marion was dead just a month when death tried to barge again into our lives. This time it came for me. Whooping Cough was my would-be assassin. That sickness left my tiny frame gasping for air, and I came within a whisper of death.

I saw no doctor because there was no money for one. Ancient remedies used by peasants for hundreds of years to combat catarrh kept me alive. Mum shrouded my head with a heavy cloth and made me- breathe in menthol mixed in a bowl of boiling water to ease the congestion in my lungs. My father carried me in his arms and willed me to live with songs and soft words about Christmas that would be soon upon us.

After a week, my sickness passed, and death departed our house unfulfilled this time. But he knew my first name now and for the next twenty years wouldn’t hesitate to call it because poverty and war are mortality’s best mates. Death during the early twentieth century knew the names of so many. It is always found among the many a multitude to snatch. Death, until the NHS was formed in 1948, had free reign to consume as many bairns as it could stomach from my generation who came from the working class.

A daughter dead in October, and a son saved in November, made our Yuletide in 1926 an occasion where funeral and feast danced cheek to cheek.

On that Christmas day, my parents splurged and kept the coal fire in the grate in our cramped parlour- burning from morning until bedtime. The day was joyous with song and merriment. My father played the piano- something he had not done since Marion died. Alberta and I stood beside him and sang well-worn festive jingles with abandon.

Mum prepared our modest holiday feast in a tiny scullery, which was found at the back of the parlour. Our Christmas tea was a small sliver of roasted meat that floated on rich gravy that was prevented from flooding off our plates by a mountainous dam of potatoes and parsnips. There was even pudding because Mum baked a jam roll that we washed down with tea- sweet with sugar.

After our meal, I played with my lone gift from Father Christmas; a toy train made in Japan because a British-manufactured toy was too costly for my parents. I sat on a rug woven from the rags of clothes too threadbare to wear and pushed my train across the surrounding stone floor that was icy cold. Near me, my sister admired the doll she was given for Christmas. Alberta and I didn't know it then, but this was the last Christmas when our parents could afford to buy us presents.

At the beginning of the New Year, calamity returned to our house. It came for my dad this time. At fifty-nine, he was no longer up to the job of working at the coalface. Decades beneath the surface, busting rock and coal had broken his body and lungs- he was demoted to the task of surface work.

In his new work, Dad accepted every demeaning command to shovel coal or haul broken equipment away from the mine entrances to preserve his employment. Dad took each order to lift, carry and fetch with good humour because he knew work kept our family out of the poor house. But his body could not keep up with the six-day workweek. The physical demands, the sheer stamina and strength needed to work ten hours a day, lifting and dumping scrap were too much for my father. The hernia he'd got from his hard labour deep beneath the surface in the world of black coal ruptured above ground when he was ordered to haul away heavy metal beams by himself.

He was done for because a manual labourer who can't before manual labour has no utility in a society that reveres capitalism. Dad was let go from the mine and in an era with insufficient unemployment benefits and where women were discouraged from working outside of the home; my family's fate was destitution.

By the time, my fourth birthday arrived at the end of February 1927, our family no longer had money to heat our home with coal. Mum enlisted my sister Alberta and me to scoff coal from a slag heap at one of the collieries near our dwelling. My sister and I would head out to the slag heap on blistering frosty winter days after- we breakfasted on watery porridge.

When we arrived at the base of the slag heap- that was piled high with the jetsam of the mine below. It looked to my four-year-old eyes like an ominous black mountain that had risen from the depths of hell because sections of it smouldered and smoked from bits of coal igniting through friction. My sister and I along, with other children with unemployed dads, ascended the mountain of slag like Sherpas going up Mount Everest.

With my tiny legs, I crawled up to its summit. At the top, I scrambled to fill my bucket with jagged pieces of substandard coal. Day in, and day out, I climbed those heaps of slag at the mouth of the colliery to fill my bucket with broken lumps of coal to keep our house warm and our oven working.

When done, I walked home; my clothes and face were covered in coal dust like I had worked a shift down in the pits below that are as deep and black as the ocean where no sunlight can penetrate.

1927 was the year my family floated in the wreckage caused by my father's unemployment. We subsisted on poor relief and midnight flits. Our welcome in Barnsley was at an end. My mother's family had nowt for us because they were mining folk too, living within a penny of their own ruin. As for my father's family, they had banished him from their hearts when he married my mother. A sister of his lived in Barnsley and owned a pub with her husband, but she refused all pleas from my father for aid to keep his bairns out of the workhouse.

By 1928, my family stood like millions of other working-class families on the threshold of the Great Depression. Like them, we didn't know what was coming for us. But we were even less prepared than most working-class people for the economic maelstrom that gathered strength on the horizon. The General Strike, followed by Dad's unemployment, meant; there was no cushion for us or minuscule reserves to draw upon. Everything was used up to survive my father's year of joblessness. Only the strong and unsentimental would survive the last years of the 1920s and the first of the 1930s.

At the start of 1928, my parents skipped out on their debts and fled Barnsley for Bradford with Alberta and me in tow. The bus that delivered us there stank of passengers who couldn’t afford a trip to the public baths and subsisted on fried potatoes and onions. Bradford didn’t promise my family much outside of the slim chance we might keep our heads above water rather than drown in poverty. It all depended on if Dad was able to find work in a larger city.

We now existed to survive- nothing more and nothing less.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John

A strong and honest description of the harrowing existence endured by the working class before the introduction of the welfare state and the NHS. This needs to be read in history classes. Sadly, I see society sinking back into this state if we don't fight against it.

Just heartbreaking reading 😞