Eleven years is a lot of water under the bridge, but Harry’s Last Stand, the first of five books by Harry Leslie Smith, was published that long ago. The publisher should have republished Harry’s Last Stand for its tenth anniversary last year. However, their business model has changed since 2014, and they contend, that “the world has moved on from Harry.”

The world has certainly moved on to be more shit than in 2014 which is quite an accomplishment. It’s moved on to being the worst cost of living crisis in modern history. It’s moved on to embrace fascism and enable genocide as a legitimate tool of the state. It has moved on to classify xenophobia as patriotism. It has moved on to normalise mass death in worldwide pandemics. We have moved on to a post-truth world. It’s probably why Harry’s Last Stand will never be republished. I hope his Green and Pleasant Land and his work on post-war Britain will find a publisher.

But we shall see because the last thing the entitled of the 21st century want are true accounts of the working class from the 20th century who were socialists, not racist and believed that everyone deserved a dignified life.

Looking back at an old travel itinerary from 2014, today was the day I travelled with my father to Bradford. We went to Bradford to visit the house that had been a doss that his family lived in for two years during the worst parts of the Great Depression.

Below are my notes about the days leading up to the publishing of Harry's Last Stand, which are written as a letter to my dad.

The Green & Pleasant Land is now complete in its beta version, and the last excerpt from it will drop on Substack this week. DM for a copy.

Rent day approaches quickly, and unfortunately due to the bad economy, I've lost some paying subscribers this month. So, I have included a tip jar for those inclined to assist me in this project.

That year, at the end of May, we flew into Manchester. For you, the city’s airport didn’t have pleasant memories because it was where you spent your last RAF posting before demob, in 1948.

The RAF sent you there as punishment for marrying Mum because marriage to foreign nationals from former belligerent powers in World War Two, although not illegal, wasn’t encouraged.

It was an attempt to demoralise you - let you know that Britain's government might be socialist but the RAF was not. Your superiors gave you one task until your discharge papers came through- smash with a sledgehammer- thousands of surplus RAF radio receivers. So as each hammer blow destroyed hundreds of pounds of salvageable equipment, you tried to plot how you would provide a good life for your new wife on civvy street.

We didn't stay long in Manchester, only one night at an airport hotel where the wait staff believed we were on holiday.

We left the following morning and took a bus to Bradford.

On the coach, you grew pensive. Gazing out at the rain-soaked moors as we drove down the M1, you said. “My whole life, I’ve hated buses. They only bring back memories of when my family went to Bradford after we fled Barnsley ahead of the bailiffs in 1928.”

The few days we spent in Bradford were emotionally uncomfortable for you. You'd not been to the city since you emigrated to Canada sixty-one years earlier. “Unlike Lot’s wife, I never looked back.” Yet you insisted on revisiting the doss you had lived in as a boy in St Andrew’s Villas. It was where all hope was abandoned for your family and the others who found accommodation under its merciless roof.

In the cab, over the noise of the windshield wipers, you said “It hasn’t stopped raining over Bradford since my family came to this town in 1928.”

Standing at the front of the doss where so much hurt had occurred to your family, you wept. After you wiped some tears away with a handkerchief, you reflected that the neighbourhood hadn’t changed much.

“It is still bleak and stinks of human suffering.”

We walked down the steep road and off in the distance. You pointed to an off-licence and said, “At seven years old, I pushed a beer barrow up this bloody hill to earn my scratch. I did that work without a proper meal in my stomach. I laboured because no one would hire my Dad."

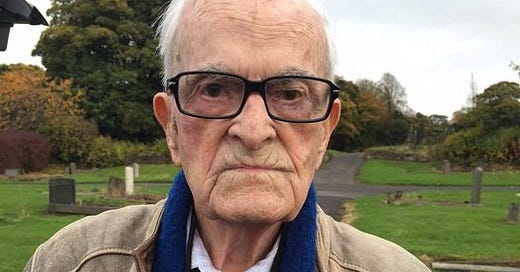

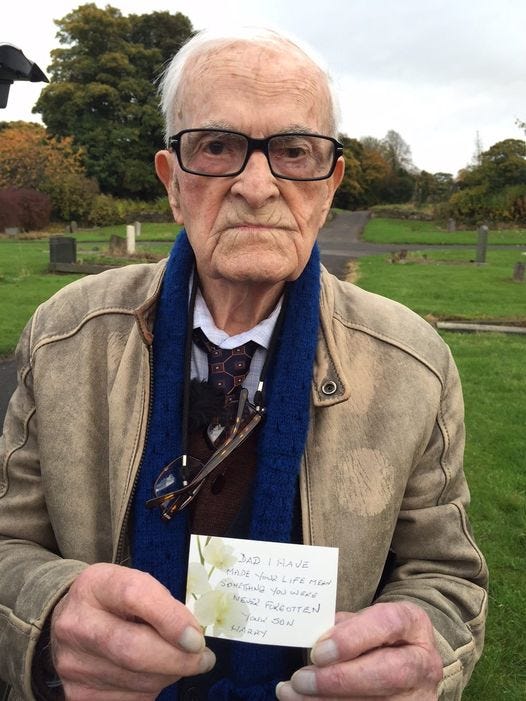

Afterwards, we took a cab to Scholemoor cemetery where dark clouds hung heavy over a damp spring afternoon. There you visited a field where, in times past, pits were dug, and thousands of indigent corpses were buried because the families of the dead were too poor to afford a proper funeral. Your Dad's remains were tossed into the ground there in October 1943.

You whispered. “I got out Dad.”

After that, you said no more. We stood silent separated by memories, you alone experienced, and I tried to interpret through the lens of a well-fed childhood.

It began to spit rain that fell as hard as pellets. “Let’s go and get a beer, I am tired of remembering,” you said, deflated by your personal history.

A few days later, we were in London to promote Harry's Last Stand. We took a cab from King's Cross to Bloomsbury and checked into a posh hotel your publisher generously booked for us. Later, the publisher’s managing director explained that he wanted you to experience how authors were treated before corporate penny-pinching did away with book launches replete with luxuries for the talent.

“Enjoy because it will never happen again for him in this business.”

He was right.

A dinner was held in your honour at the Garrick Club the night before the publication of Harry’s Last Stand. The guests were employees from your publishing company, your agent, the chief book buyer from Waterstones, and Bella Mackie from the Guardian, who fawned over you like an adoring grandchild. But then again, she felt she had discovered you as she promoted your essays to the editors of the Guardian where she then worked. Your support for Corbyn eventually cooled her support for you, and contact during your last years trailed off. You were politely ignored in hopes that you would change your views on Corbyn and denounce him to obtain column inches. After you died, she wrote a loving farewell to you in the Guardian and then blocked me on social media.

That night, the Guardian published an excerpt from the book. In real-time, I watched your fame on social media grow while Amazon book sales soared to number 32 in the nonfiction section. No other book of yours would ever go that high again in online sales. When the dinner was over, we returned to our hotel room had a nightcap and danced together. We believed we had established a strong beachhead, or, at least, a compelling argument for society to revisit Labour’s policies of socialism from 1945. Dancing that night with you reminded me of Christmas Eve 1987 when you, Peter, and I- drunk on Port wine, danced to 1940s jazz tunes until 4 in the morning.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and allows me to preserve Harry Leslie Smith's legacy.

A yearly subscription will cover much of next month’s rent. All I need is 6 subscriptions to make June’s payment. But with four days to go, it is getting tight.

Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co-morbidities, which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost-of-living crisis times. If you can, please join with a paid subscription, which is just 3.50 a month, or a yearly subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. If you can’t, it's all good, because we are in the same boat.

Take Care, John

I have not moved on from your dad. I am looking forward to your new book, and would welcome a beta copy.