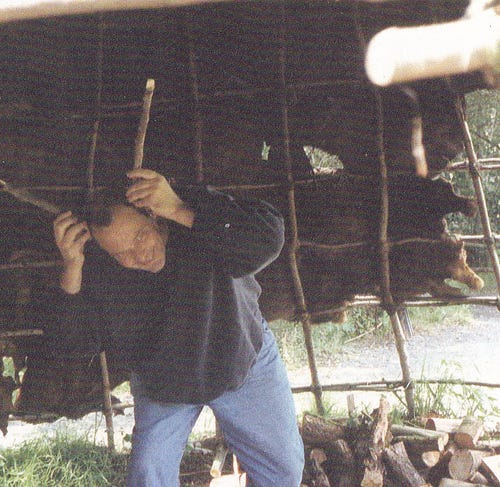

“Pete in his early years: a life of art, curiosity, and boundless energy.”

Dead sixteen years, but today is my brother Pete’s birthday. I will be of good cheer and raise a glass of beer to him as I eat yesterday’s leftovers. I’ll think of his time that was, and the time that wasn’t, that makes up those moments called could have been.

The death of someone you love is an amputation done without anaesthetic.

A portion of your spirit—or soul, call it what you will—is violently torn from your life. The phantom pain from that loss lasts forever. Scar tissue covers the memory, but it’s easily reopened.

My brother marked his fiftieth—and final—birthday in an ICU bed. A respirator kept his lungs moving after a botched exploratory surgery three weeks earlier had caused irreparable damage to organs already ravaged by pulmonary fibrosis.

The respirator left him unable to speak, so he communicated through hand gestures. To soften the harshness of the ICU, Peter’s wife taped photos from his life on the wall near his bed.

“Take them down,” he mouthed to me, as the respirator hissed and exhaled oxygen into his failing lungs.

I did so. He tapped the side of his bed to stop me when I reached the photos of him as a young child. I stepped back. For the little time he had left, Pete fixed his eyes—and his imagination—on the moments when his life still held some degree of normalcy.

Peter died too young. Even staying alive for half a century had been, for Pete, as arduous and precarious as climbing Mount Everest without oxygen cylinders. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his twenties and pulmonary fibrosis in his late forties.

In the last year of his life, he told me he couldn’t remember when he didn’t hear voices in his head mocking and abusing him, distorting his reality.

When Pete was twenty-six, I wouldn’t have guessed mental illness stood around the corner, ready to rob him of his sanity and a normal progression through life. He was an artist on the verge of recognition, a recent art college graduate and a scene painter for the Toronto Ballet Company. His social life was exciting, and he was in a relationship.

During my youth, I loved and envied my brother. Pete introduced me to the music of Elvis Costello, the films of Fellini, the socialist historian A.J.P. Taylor, the novels of Steinbeck, and scotch whisky on a Saturday night while listening to jazz.

Pete was confident, generous, and kind. He took after our father in loyalty and hard work. He was a non-conformist who marched to the beat of his own drummer and wasn’t afraid to stand up to bullies.

At twenty-eight, Pete suffered a series of severe psychotic episodes. These were symptoms of schizophrenia he had managed to conceal for most of his twenties, but now they overwhelmed him. He was admitted to a psychiatric ward and treated with medication and talk therapy. My family, especially me, remained in deep denial about how irrevocable his illness had become.

The disease disabled him to the point that he could no longer work. He lost his job, and friends, disturbed by his behaviour, abandoned him. Had my parents not taken him back into their home, I have no doubt my brother’s life would have ended in suicide. Severe mental illness is a brutal test of even the strongest love. It took a heavy toll on my parents and all of us, and his premature death still makes me feel that I failed him when he needed me most.

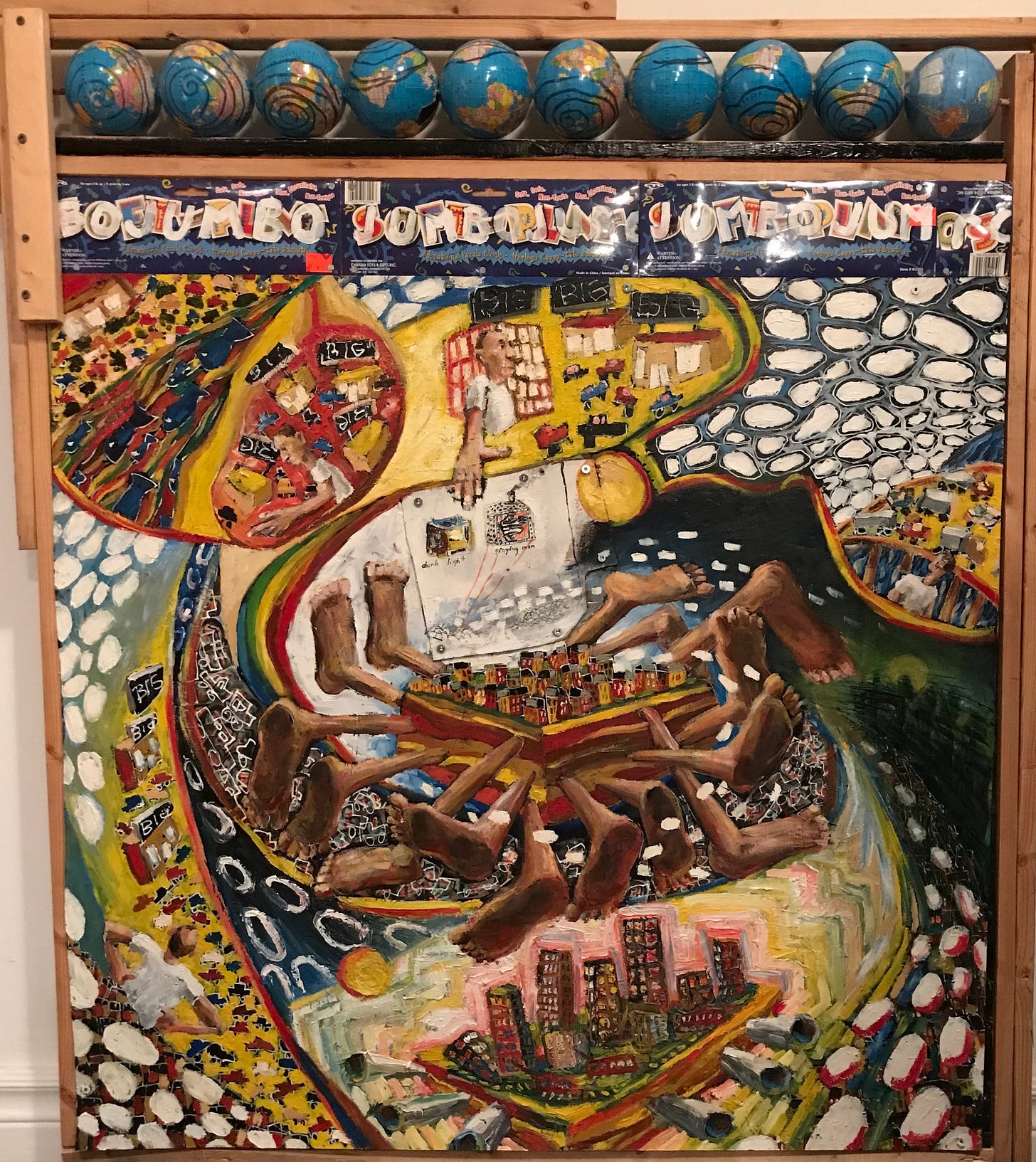

During the mid-1990s, Peter’s mental illness stabilised. Our father encouraged him to resume his artwork, which not only saved his life but gave him a sense of worth that society denies to so many. Through his art, he documented the harsh journey schizophrenia forced him to take across the geography of his spirit. His work captured the tragedy and comedy of existence. Beauty, love, rage, desire, joy, and humour all found their way into his paintings, woodcuts, and sculptures.

Peter longed for a purposeful life, filled with love and as much normalcy as possible, and for a brief time, he achieved it. In 1999, he married his girlfriend, and they moved into an artist co-op housing complex in Toronto. During those first years of marriage, Pete served as an art mentor for people with mental health issues at Ontario’s Clarke Institute. He was gaining recognition for his talent, appearing in art magazines, winning juried competitions, and exhibiting in notable Toronto galleries.

After decades in the wilderness, Peter was on the cusp of being discovered by the art world. But life is not fair. At forty-eight, he developed a persistent cough. He blamed it on cheap cigarettes bought on the black market. It was not the cigarettes. It was something far worse: his lungs had become fibrotic.

“Premonition: Peter’s art reflects the fragility of life and his confrontation with mortality.”

By the time he turned forty-nine, Peter’s breathing had worsened. He spent that year in his studio, trying to capture more of his story on canvas and wood carvings. Many of these works hint at a premonition of his death, showing him on a hospital bed with a tube in his throat. Near the end, Peter said of his life, “It’s been a fucking blast.” He died in hospital just twenty days after his fiftieth birthday.

I wish Peter could have lived to sixty-six; those extra years would have allowed him so much more to express as an artist and to live fully as a human being. Yet at times, I think maybe it would have been better if he had just lived until Dad died in 2018 and not witnessed the COVID pandemic. Pete’s schizophrenia would not have been easy during that period or the age of fascism that followed.

My brother made my life less lonely, and I suspect I did the same for him, because I could make him laugh. He was my big brother: protective, irritating, loving, and generous.

Some of Pete’s artwork adorns the walls of my apartment. It consoles me, because in it I see the moments of his life through his eyes rather than my own. His artwork reminds me of my purpose for the remainder of my life. I am here to preserve my family’s working-class legacy of socialism, art, and literature. They endured and loved in the harshest conditions, giving back more to the world than they took.

Ah, Pete, here ends another year in which you are dead, except in my heart and memory. Three cheers for the days when you lived, and when Mum and Dad were also alive. Those long-ago days had their share of sunshine and storms, yet they were always filled with more promise than despair.

My rent is coming due, and it always feels like I spend the days leading up to the first of the month as a desperate character from Berlin Alexanderplatz, madly trying to keep a roof over my head. These are the times we live in—they aren’t lucky for many of us.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy alive—and keeping me afloat—is deeply appreciated. I rely on your subscriptions to keep the lights on and a roof over my head. If you can subscribe, thank you. If not, that’s perfectly fine—we are fellow travellers navigating these hard times together. But please, always share these posts far and wide. So many of us lose precious time on the work that matters because of the scramble just to pay rent and feed ourselves during an economic crisis not seen since the 1930s.

Your subscriptions are crucial for my survival. Like so many others struggling to keep afloat, my day-to-day life is precarious, made harder by battling cancer, lung disease, and other co-morbidities. October rent is approaching, and I need six yearly subscribers to cover it. There is also a tip jar for those who are inclined.

Take care,

John

P.S. Tomorrow, I’ll share a large collection of my brother Pete’s paintings.

Thanks for sharing this story and the pictures of the artwork. Your writing is as moving as your dad's.

Your brother was very talented, John. It's very sad that he died so young, especially as he also lost time through his illness. I always enjoy it when you share some of his work and I'm looking forward to the collection that you have selected for us to see tomorrow.