The NHS marked its 75th anniversary as a public institution this past July. It won't live to see 80 under a Keir Starmer government. Starmer said today the NHS must-

"Reform or die."

When a neoliberal Prime Minister says that- it means one thing- public healthcare will be surrendered to the private sector.

There are few left alive from when the NHS was born in July 1948. However, when it dies at the hands of neoliberalism, we will all be at its bedside.

The death of the NHS is the end of democracy because, without public healthcare, a citizen's ability to exist is solely dependent on how much profit they can earn for the entitled.

Nobody from the ordinary classes has any control over Starmer's government, and the corporate news media is not on our side.

Except for a few outliers, there isn't anyone who represents the many in parliament. It may as well be Russia's Duma under a Putin Presidency.

Despair is a penny a plate because of this abandonment by the political class.

The past is our future and it is coming at us like the headlights from a drunk driver's car driving directly into us.

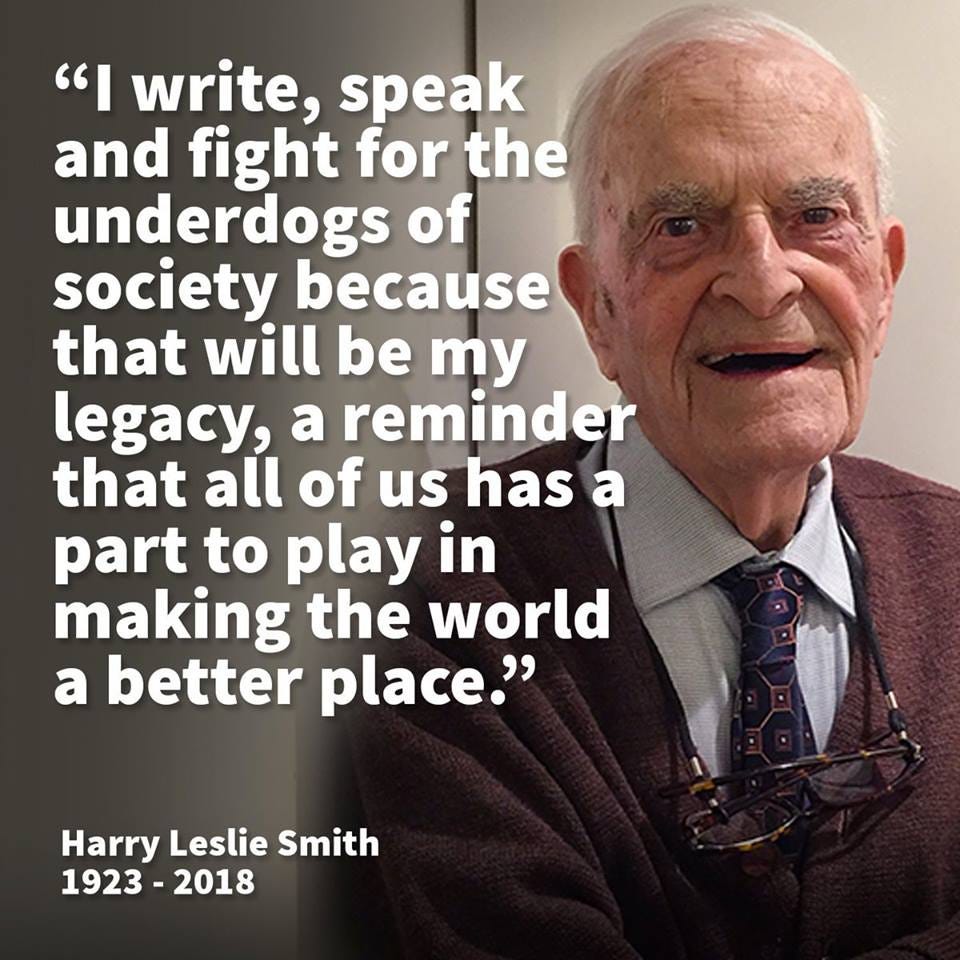

The Harry’s Last Stand project, which I worked on with my Dad, for the last 10 years of his life, was an attempt to use his life story as a template to effect change and remake a Welfare State fit for the 21st century. Below is one of the many essays from that project that are still relevant to the battle we wage today to stop his past from becoming our future.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going, and me alive is greatly appreciated. I depend on your subscriptions to keep the lights on and me housed. So if you can, please subscribe, and if you can’t -it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury. But always remember to share these posts far and wide.

There is now a tip jar available if you are so inclined. Cheers, John.

Over 90 years ago, I was born in Barnsley, Yorkshire, to a working-class family. Poverty was as natural to us as great wealth and power were to the aristocracy of that age. Like his father and grandfather before him, my dad, Albert, eked out a meagre existence as a miner, working hundreds of feet below the surface, smashing the rock face with a pickaxe, searching for coal.

Hard work and poor wages didn’t turn my dad into a radical. They did, however, make him an idealist, because he believed that a fair wage, education, trade unions and universal suffrage were the means to a prosperous democracy. He endured brutal working conditions but they never hardened his spirit against his family or his comrades in the pits. Instead, the harsh grind of work made his soul as gentle as a beast of burden that toiled in desolate fields for the profit of others.

My mother, Lillian, however, was made of sterner stuff. She understood that brass, not love, made the world go round. So when a midwife with a love of gin and carbolic soap delivered me safely on a cold winter’s night in February 1923 into my mum’s exhausted arms, I was swaddled in her rough-and-ready love, which toughened my skin with a harsh affection. I was the first son but I had two elder sisters who had already skinned their knees and elbows in the mad fight to stay alive in the days before the social safety network. Later on, our family would include two half-brothers, after my mother was compelled to look for a more secure provider than my dad during the Great Depression.

By the time I was weaned from my mother’s breast, I had begun to learn the cruel lessons that the world inflicted on its poor. At the age of seven, my eldest sister, Marion, contracted tuberculosis, which was a common and deadly disease for those who lived hand to mouth in early-20th-century Britain. Her illness was directly spawned from our poverty, which forced us to live in a series of fetid slums.

Despite being a full-time worker, my dad was always one pay packet away from destitution. Several times, my family did midnight flits and moved from one decrepit single-bedroom tenement to the next. Yet we never seemed to move far from the town’s tip, a giant wasteland stacked with rotting rubbish, which became a playground for preschool children.

At the beginning of my life, affordable health care was out of reach for much of the population. A doctor’s visit could cost the equivalent of half a week’s wages, so most people relied on good fortune rather than medical advice to see them safely through an illness. But luck and guile went only so far and many lives were snatched away before they had a chance to start. The wages of the ordinary worker were at a mere subsistence level and therefore medicine or simple rest was out of the question for many people.

Unfortunately for my sister, luck was also in short supply in our household. Because my parents could neither afford to see a consultant nor send my sister to a sanatorium, Marion’s TB spread and infected her spine, leaving her an invalid.

****

The 1926 General Strike, which began just as my sister started her slow and painful journey from life to death, was about more than wages to my dad and many others. It was called by the TUC in protest against mine owners who were using strong-arm tactics to force their workers to accept longer work hours for less take-home pay. At its start, it involved 1.7 million industrialised workers.

In essence, the strike was about the right of all people, regardless of their economic station, to live a dignified and meaningful life. My father joined it with enthusiasm, because he believed that all workers, from tram drivers to those who dug ore, deserved a living wage. But for my father the strike was also about the belief that he might be able to right the wrongs done to him and his family; if only he had more money in his pay packet, he might have been able to afford decent health care for all of us.

Unfortunately, the General Strike was crushed by the government, which first bullied TUC members to return to their work stations. Eight months later, it did the same to the miners whose communities had been beggared by being on the pickets for so long. My dad and his workmates had to accept wage cuts.

I remember my sister’s pain and anguish during her final weeks of life in October 1926. I’d play beside her in our parlour, which was as squalid as an animal pen. She lay on a wicker landau, tied down by ropes to prevent her from falling to the ground while unattended. When Marion’s care became too much for my mother to endure, she was sent to our neighbourhood workhouse, which had been imprisoning the indigent since the days of Charles Dickens.

The workhouse where Marion died was a large, brick building less than a mile from our living quarters. Since it had been designed as a prison for the poor, it had few windows and a high wall surrounding it. When my sister left our house and was transported there on a cart pulled by an old horse, my mum and dad told my other sister and me to wave goodbye, because Marion was going to a better place than here.

The workhouse was not used only as a prison for those ruined by poverty; it also had a primitive infirmary attached to it, where the poor could receive limited medical attention. Perhaps the only compassion the place allowed my parents was permission to visit their daughter to calm her fears of death.

My sister died behind the thick, limestone walls at the age of ten, and perhaps the only compassion the place allowed my parents was permission to visit their daughter to calm her fears of death. As we didn’t have the money to give her a proper burial, Marion was thrown into a communal grave for those too poor to matter. Since then, the pauper’s pit has been replaced by a dual carriageway.

****

Some historians have called the decade of my birth “the Roaring Twenties” but for most it was a long death rattle. Wages were low, rents were high and there was little or no job protection as a result of a postwar recession that had gutted Britain’s industrial heartland. When the Great Depression struck Britain in the 1930s, it turned our cities and towns into a charnel house for the working class, because they had no economic reserves left to withstand prolonged joblessness and the ruling class believed that benefits led to fecklessness.

Even now, when I look back to those gaslight days of my boyhood and youth, all I can recollect is hunger, filth, fear and death. My mother called those terrible years for our family, our friends and our nation a time when “hard rain ate cold Yorkshire stone for its tea”.

I will never forget seeing as a teenager the faces of former soldiers who had been broken physically and mentally during the Great War and were living rough in the back alleys of Bradford. Their faces were haunted not by the brutality of the war but by the savagery of the peace. Nor will I forget as long as I shall live the screams that fell out of dosshouse windows from the dying and mentally ill, who were denied medicine and solace because they didn’t have the money to pay for medical services.

Like today, those tragedies were perpetuated by a coalition government preaching that the only cure for our economic troubles was a harsh austerity, which promised to right Britain’s finances through the sacrifice of its lowest-paid workers. When my dad got injured, the dole he received was ten shillings a week. My family, like millions of others, were reduced to beggary. In the 1930s, the government believed that private charities were more suitable for providing alms for those who had been ruined in the Great Depression.

Austerity in the 1930s was like a pogrom against Britain’s working class. It blighted so many lives through preventable ailments caused by malnutrition, as well as thwarting ordinary people’s aspirations for a decent life by denying them housing, full- time employment or a proper education.

As Britain’s and my family’s economic situation worsened in the 1930s, we upped sticks from Barnsley to Bradford in the hope that my father might find work. But there were too many adults out of work and jobs were scarce, so he never found full-time employment again. We lived in dosshouses. They were cheap, sad places filled with people broken financially and emotionally. Since we had no food, my mum had me indentured to a seedy off-licence located near our rooming house. At the age of seven, I became a barrow boy and delivered bottles of beer to the down-and-outs who populated our neighbourhood.

My family were nomads. We flitted from one dosshouse to the next, trying to keep ahead of the rent collector. We moved around the slums of Bradford and when we had outstayed our welcome there, we moved on to Sowerby Bridge, before ending up in Halifax. As I grew up, my schooling suffered; I had to work to keep my sister, my mum and half-brothers fed. At the age of ten, I was helping to deliver coal and by my teens, I started work as a grocer’s assistant. At 17, I had been promoted to store manager. However, at the age of 18, the Second World War intervened in whatever else I had planned for the rest of my life. I volunteered to join the RAF.

****

My politics was forged in the slums of Yorkshire but it was in the summer of 1945, at the age of 22, that I finally felt able to exorcise the misery of my early days. In that long ago July, I was a member of the RAF stationed in Hamburg; a city left ruined and derelict by war. I had been a member of the air force since 1941 but my war had been good, because I had walked away from it without needing so much as a plaster for a shaving nick. At its end, my unit had been seconded to be part of the occupational forces charged with rebuilding a German society gutted by Hitler and our bombs.

It was in the palm of that ravaged city that I voted in Britain’s first general election since the war began. As I stood to cast my ballot in the heat of that summer, I joked with my mates, smoked Player’s cigarettes and stopped to look out towards a shattered German skyline. I realised then that this election was momentous because it meant that a common person, like me, had a chance of changing his future.

So it seemed only natural and right that I voted for a political party that saw health care, housing and education as basic human rights for all of its citizens and not just the well-to-do. When I marked my X on the ballot paper, I voted for all those who had died, like my sister, in the workhouse; for men like my father who had been broken beyond repair by the Great Depression; and for women like my mum who had been tortured by grief over a child lost through unjust poverty. And I voted for myself and my right to a fair and decent life.

I voted for Labour and the creation of the welfare state and the NHS, free for all its users. And now, nearly 70 years later, I fear for the future of my grandchildren’s generation, because Britain’s social welfare state is being dismantled brick by brick.

Thanks for all your continuing support. You have been great, and I am so pleased my Substack has nearly 2400 subscribers- 228 of which are paid. I am building a community with your help. But it is slow and arduous work.

In August I published over 25k words here, which is a lot of words. To be honest too many words. If I wasn't so short of cash the post would be fewer but more polished. But that isn't happening anytime soon if ever. I still have a bit to cover for my rent. So, if you can and only if you can please subscribe to my Substack or use the Tip Jar. I am reducing a yearly subscription by 20% because it is a fire sale, of sorts. Take care because I know many of you are sharing the same boat with me.

It's hard to feel anything but despair 😔

End of NHS has been a long term strategy of the tory minded politicians and their paymasters.

There's a paperback book called, "This won't Hurt" covering the relationship between junior doctor and consultants and the erosion of the NHS.

On the plus side the NHS is the one institution that the British public hold as a right.

It all depends on what is meant by reforms...... As in anything to do with politicians, "Trust no one Claudius", is the best advice.