My grandfather, Albert Smith, died today in 1943. When he was 12, he began working in a coal mine dug under the village of Barley Hole. He had a hard life. My father remembered him as a gentle soul

.

He wasn't one to raise his voice or be physically violent. He was interested in history, could play the piano and was a socialist.

These are amazing accomplishments- if you consider- my granddad worked 10 hours a day, six days a week. Albert Smith didn't have a happy life or a happy ending because my grandmother abandoned him during the Great Depression. She didn't have much choice as my grandad had injured himself in a mining accident and was unemployable. In the 1930s, you don't work; you don't eat.

So, my grandmother was compelled to find another man- one who was employed and willing to take care of her and her three children. For the poorest during the Great Depression, it was similar to being on a lifeboat after a ship had sunk. The weak were sacrificed so that those with more strength could survive. But survivors have guilt, and my father had his fair share of, "survivor guilt."

Below is an excerpt from Standing With Harry about my dad coming to terms with what had happened to his father so many years previous.

************************************

You didn’t find out until Christmas 1943 that your dad was dead. Your sister wrote. “Our dad died, his heart gave out.”

“He died and was dumped in a pauper’s pit forgotten by everyone- even by me.”

You hadn’t seen your dad since 1931 when you were a boy of eight. “I couldn’t remember his face or how he smiled or laughed. All I remembered from the last time I saw him was that he was bald, stooped and his gut bulging from a fat hernia.”

That letter, the news your dad had died, picked away at the scab you had let grow over the memories of your boyhood. Since childhood, you carried so much anger, shame, resentment, and despair.

Your dad’s death occurred over 75 years ago, but it visibly upset you, and you wept as if it had happened yesterday. It stuck out in your mind like glass jutting through torn skin.

During the war when you were in the RAF, you hid much of your early poverty. You concealed your lack of formal education by memorising poets and the plays of Shakespeare, along with comedy bits you heard on the radio from Bob Hope or Bing Crosby. You hadn’t learned cursive at school because you were too busy trying to keep alive. But your printed letters were written with so much speed no one questioned it. The letter, however, about your dad’s death brought home how utterly shitty your early life had been.

That evening you got a pass to go into town. You went alone to a pub and drank beer until you were so drunk you could forget all the trauma from your childhood.

No one knew or would know your dad had died because they thought he was already dead. You had made up a lie about your dad; so no one would question your past. You said your father had died in the pits. There was an element of truth in that because the moment he injured himself, he was a goner.

You told them your mother had married Bill Moxon, which was a lie because she had never divorced your dad. She even collected a widow's pension after your father died. She refused to marry her lover Bill until he was old enough to collect a pension.

"I had to think about my old age because no one else would."

Your dad’s death was the halfway point in your first book. When that chapter was finished, you said to me. “You understand my whole life is based upon bullshit. I am always trying to recreate myself and make myself forget. In concealing my past, I was trying to make myself worthy of love.” Working on that first book with you, helped me understand how poverty destroyed your potential and the potential of millions of others whose only fault was to be born skint.

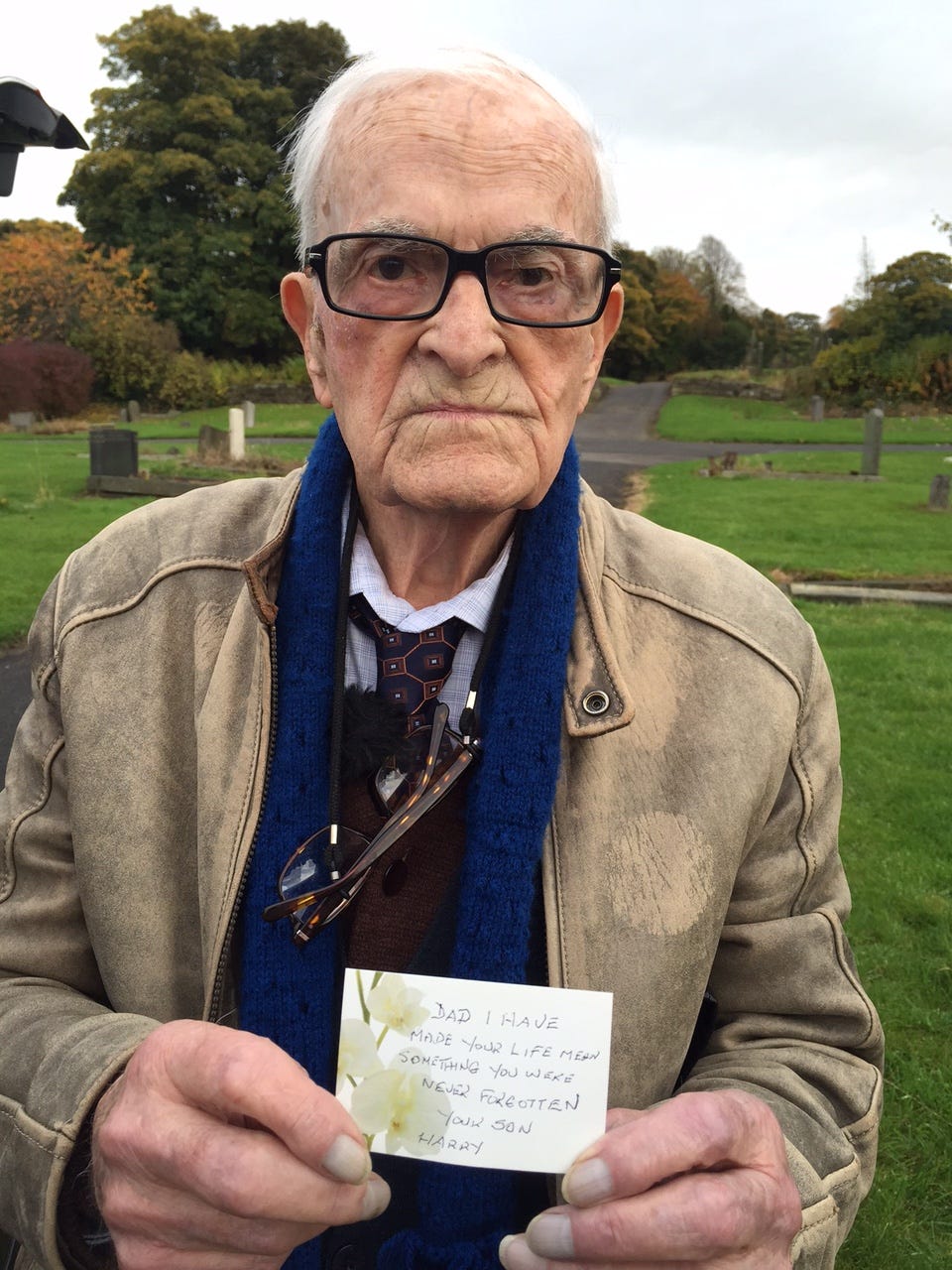

A week before Harry's Last Stand was published, we were in Bradford. I arranged for us to visit the unmarked spot where your dad was buried at the cemetery.

When we arrived at Scholemoor cemetery, dark clouds hung heavy over a damp spring afternoon. We walked to a field where- in times past, pits were dug to bury the indigent of Bradford. Over the years, thousands of paupers were buried there.

You whispered.

I got out Dad.

After that, you said no more. We stood silent, separated by memories you alone experienced.

It began to spit rain that fell as hard as pellets.

“Let’s go and get a beer. I am tired of remembering.”

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going, and me alive is greatly appreciated. I depend on your subscriptions to keep the lights on and me housed. So if you can, please subscribe. And if you can’t -it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury. But always remember to share these posts far and wide. The Green & Pleasant Land, the project my Dad was working on at the time of his death is almost ready. I hope to have the chapters sorted by my birthday on October 22nd,

I always find it heartbreaking to read about your grandfather and how cruelly life treated him. What might he have done if he had been given the opportunity to achieve his potential? His children's lives would certainly have been happier if he had been there to love and care for them. The long march of everyman continues, but I do not like the direction in which we seem to be heading.

So much emotion wells up in me, the good men in this world and how they shaped our course. Tragedy after tragedy we trudge on. My soul wraps around yours John.