Much like today, the summer of 1930 was harsh and hungry for Britain's working-class.

Hello all,

I am uploading, to a separate subfolder, Harry Leslie Smith's The Green & Pleasant Land which my dad was working on up until his death, in 2018. So far, 18 thousand words of it are available her on this Substack. Much of the 80k world manuscript will be online by July 5th. It will then proceed to further revisions and inclusions of text that I believe would satisfy my father's vision for this book.

It is an important book about the ordinary struggles of Britain's working classes until the election of the 1945 Labour government that transformed the nation into a progressive Welfare State.

Society is broken. Democracy does not function as it was intended. The system is not a for and by-the-people institution anymore. It works for the select entitled few. It can't be repaired, unless we rebuild a Welfare State fit for the 21st century. Democracy won't survive neoliberalism, and should we continue on this path- most of us will envy the dead.

All chapters can be found in the Green and Pleasant Land subsection of this Substack.

The Green & Pleasant Land:

Chapter Nine

The summer of 1930 was harsh and hungry for Britain's working-class.

There was no smell of warm rain on the grass that summer. There was no taste of Dandelion and Burdock pop chilled on a cellar's stone floor to quench your thirst.

Instead, summer reeked of mouldy potatoes fried in cheap margarine washed down with tea made from leaves flavourless from reuse.

On those long sunlit days, desperation calved in Mum's consciousness. It stumbled forth into the world, wet behind the ears, but it soon matured into a concrete idea to dump my father and find a man fit enough to do a day's labour.

As for Dad, resignation to his fate germinated and grew deep roots within his soul. Dad took the role Mum had cast him, like an actor desperate to play any part for a bit of the limelight. He was now our "granddad," in public while Mum pretended to be a young widow pregnant with her dead husband's child.

It was an intricate, sad web my mother wove. Eventually, it would trap not only her desired prey but also Mum. She never escaped how she abandoned my father or the guilt it produced for being compelled to concoct that lie to ensure some sort of future for her children and herself.

Like all the seasons I lived through during my boyhood, it was my sister, Alberta, whom I looked to for companionship and mentoring. She was my best teacher on how to survive the unrelenting cruelty of poverty in the 1930s.

Alberta was wise to the streets and wise to the machinations of adults. She taught me, in winter, how to forage through restaurant bins for my tea. Now, in summer, she showed me the ropes on the best ways to harvest specked fruit that the mongers binned.

But shop owners did not take kindly to kids, who came from the barren land of doss house Bradford nicking dented and bruised fruits that were rubbish to them.

Alberta lectured me on the need for speed and quiet when we dug through refuse to pick the well-ripened fruit- that when we bit into it- dripped sweetly into our empty stomachs.

When darkness came to the day or the sun rose on it, my childhood, that summer, was shaded in hunger. But also, I felt as only a small child can, wonder at the mundane and profound sights and events occurring all around me.

In that long ago time; I learned what I have known and cherished ever since, there is magic to being alive and aware.

Our street, Chesham, ran onto Great Horton, which ended up in a large open field called Trinity. One afternoon, my sister and I heard rumours that a circus had set up their tents on the common.

Alberta and I made our way up the street, where we discovered that the clearing tents had been erected. There was a sound of hammers being struck on tent pegs while the foreman swore at workmen to be "quick about it."

Not wishing to be discovered, Alberta and I went to the opposite end of Trinity Field. There, we were camouflaged by tall grass. In the distance, I heard the sounds of exotic animals bellowing from the field. We crouched on our hind legs and strained our eyes, hoping to catch sight of this mysterious world being built around us.

The odd elephant trumpet made our mouths drop open in surprise. I was tinged with mild fear, wondering if the mighty beasts could break loose and trample us hidden in the brush. An hour had almost passed, and I grew restless. I was about to ask my sister if we could go when suddenly, Alberta began to shake my shoulder,

“Harry, Harry, come and look.”

Outside one of the tents were three beautiful, lithe Burmese women whose necks were wrapped tightly with gold bands. Near them, jugglers began to practice their act. It was a cacophony of different voices, with different accents, different attitudes, and different lives from ours in the slums of Yorkshire. Further off, I heard lions roar and in my imagination, it was lion speak for "bugger off Bradford."

Everything I saw that day crouched and hidden at the edge of a circus in the long unkempt grass of the common- was enticing, forbidden, and beautifully foreign to the world as I understood it.

The Green & Pleasant Land

Chapter 10:

Mum was in her eighth month of pregnancy during the dog days of August in 1930. The weather was sultry, and our neighbourhood stank of people's sweat and clothing in sore need of washing in soap and water.

Our threadbare squat on Chesum Street was unbearable from the heat of the sun and the burning rage that exploded out from my mother's mouth to my dad for the injustice of our poverty.

She was short-tempered with Dad because instead of finding fault with capitalism for causing the Great Depression, he was made to blame for our personal destruction.

Hungry, angry and pregnant mum was a beast best avoided. So, I did not complain when I was packed off to spend the remainder of the summer in Barnsley with my grandparents. Alberta was not sent with me because- being ten- she was considered old enough to work as a part-time laundress, which provided extra pennies to afford bread for the nightly tea of drippings.

In a few months, and to my great despair, I was also destined to be pressed into child labour to prevent my family from becoming utterly destitute.

Mum walked with me to the station, where a bus to Barnsley awaited. I carried a sack packed with a change of clothes.

My mother barked at the bus driver, the correct stop for him to let me off at.

"Uncle Harold will meet you where the bus drops you off and walk you to Grandma Dean’s house.”

My uncle Harold, as promised, was there waiting for me when my bus reached Hoyland Common, near where my grandparents lived.

Harold was thirty years old, thin as a rail and, sarcastic and imbued with a nervous energy that radiated off him as if it was static electricity.

He spoke to me as he did to adults in short, brutally sarcastic sentences. Harold was married to Ida, whom he adored because she softened the harsh edges of his personality. He, Ida and my uncle Ted lived with my grandparents.

Harold did not hide from me his detestation of my mother.

At each street corner, Harold called Mum a “whore, bitch” or something else equally offensive.

My grandparents lived on Beaumont Street in a two-bedroom tenement house. It had a ginnel leading onto a back plot where a privy and small vegetable garden was located.

When I arrived, my 73-year-old Granddad, Walter Dean was fast asleep on a chair in the parlour.

He was retired, but before old age allowed him to slumber his last days away, he was a miner and a soldier for Queen Victoria.

He never saw battle, but you would have never known that from how he talked about life in the Artillery.

He served in India in the 1890s. He was an oppressed working-class soldier who oppressed others in Britain's pursuit of Imperial and economic domination- across the world.

Grandad spent ten years in India and departed the military, with no trade to enhance his earning potential on civvy street to make life easier for himself, his wife and seven children.

He didn't think much of me because I didn't think much of the medals he earned by taking the Queen's shilling when he showed them to me one night before bedtime.

Like Harold, my Granddad didn't like my mother much either.

From a child’s perspective, he resembled a gruff walrus who laboured to stand. He believed in monarchy, empire and the class system, where he was proudly at the bottom of it.

My grandmother, Mary Ellen, like my grandad, held strong opinions on my mother, which were generally negative.

She always wore petticoats and a heavy wool dress that swept the floor around her as she walked.

She never raised her hand or voice in my direction, nor did she hug me. My grandmother was aloof, set in her ways, but that didn't bother me.

What was more important than love at that time in my life was food and that was plentiful in my grandparents' household. That I didn't need to hunt for my tea by scavenging through restaurant rubbish bins seemed miraculous.

There were three meals a day for me to eat was a novelty to be savoured.

During those weeks I spent at my grandparents' house in the summer of 1930, Uncle Ted was the one whose company I enjoyed the most. He possessed a gentle quietness, which I found appealing coming from a household filled with- so much hidden noise and anger.

Later on, when Ted retired from the pits, in the 1950s, he took to the open roads in summer and autumn with a horse-drawn caravan won in a card game.

Ted tended the vegetable patch behind my grandparents' house that supplemented their meals in summer with fresh produce. I'd find him there in the mornings, carefully and solicitously weeding the small garden.

He let me eat ripened fruit from the small plot, which I savoured, remembering how in June, I stole apples from fruit mongers.

Ted did not speak much, and when he did, everything was in short syllables,

“mind this” or “yer alright there.”

But it was spoken from a calm river inside him, which relaxed me.

Harold's wife Ida worked as a bookkeeper on a large industrial farm and lodged there on weekdays. She was revered in the family because she had a trade that used its brain rather than brawn. Tragically, she died young and left Harold a widower for 50 years before he died in 2004, hateful of everyone in the world for scoffing love from underneath him.

Ida gave me the means to learn one of the most valuable skills a poor lad in the 1930s could acquire; the knowledge of how to ride a bike.

Ida lent me her bike and, with it, gave me the freedom to roam far from the troubles of adults around me.

The only instructions from Ida were to get on the bike and pedal as fast as my legs would allow me. But my feet reached the thick wooden pedals. The first day on it I suffered, scrapes, bangs and bitter disappointment that riding a bike was harder than it looked.

By the second day, I was able to keep on the bike and keep it steady for longer periods.

Many attempts and many aborted take-offs would ensue. But gradually, I developed my wings. I was able to pedal and remained balanced and aloft for longer periods.

I was ready to discover the hills and dales surrounding my grandparent’s house. I’d spend my mornings and afternoons riding this bike. I was free of the burdens of hunger. I was away from my parents' despair and hunger for better lives.

I was free of my own sense of shame because of our poverty. On this bike, I could pedal faster than the storm clouds of the Great Depression all around me.

As with all things in my early life, these sheltered moments of calm were brief. The summer winded its way through my grandparent’s house on Beaumont Street until one morning, it all ended with a "Time to go, lad," from Uncle Harold.

I returned to Bradford, where my sister patiently waited for me at the bus station. We walked home in silence because I was afraid to ask if things were worse with my mother and father.

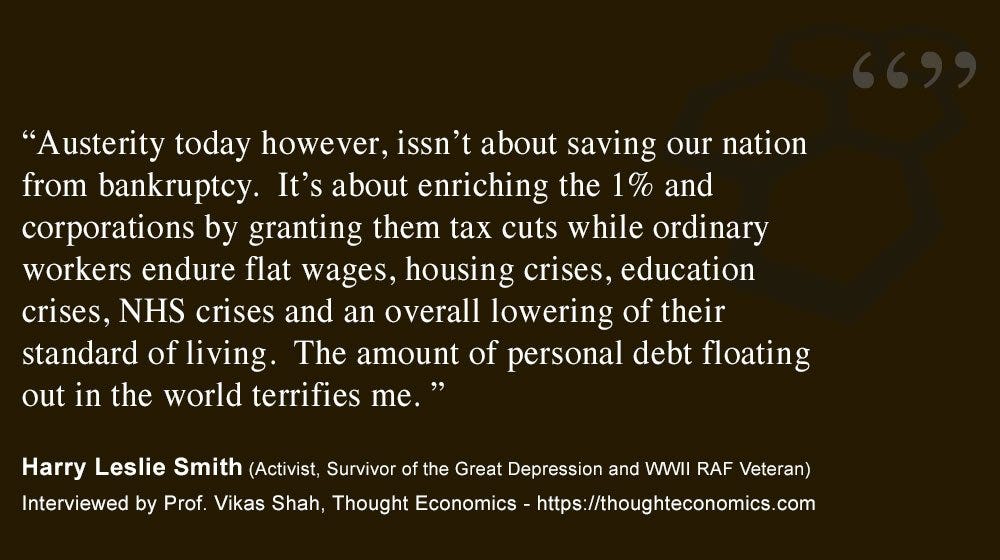

Summer had turned into fall.. Breadlines increased as the dole dried up. The working class, particularly my mother hurled invective at Prime Minister Ramsey Macdonald and his betrayal of the people by signing off on Tory austerity.

More workers were sent home from their jobs because the politicians refused to support reconstruction projects or stimulate the economy. Now, it was time for the real famine to commence in Britain.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. A yearly subscriptions will cover much of next month’s rent. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John