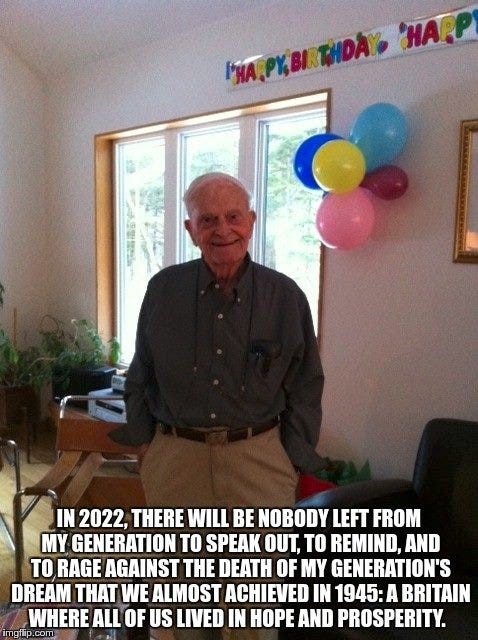

The Green & Pleasant Land is almost ready to be sent to a publisher. It’s the unfinished work my Dad laboured on before his death in 2018 . I have spent the last year bringing to life from his notes, drafts and index cards.

The book is an intimate look at poverty. My father learned first-hand how destitution dissolves a family's love for each other with the harshness of acid touching human skin. It's a political testament of outrage about the lost potential of the working class, who then- like now were chained to lives of hungry drudgery.

The Green & Pleasant Land is an important to read at this juncture in our history. Society is broken. Democracy does not function as it was intended. The system is not a for and by-the-people institution anymore. It works for the select entitled few. It can't be repaired, unless we rebuild a Welfare State fit for the 21st century. Democracy won't survive neoliberalism, and should we continue on this path- most of us will envy the dead.

It might even be too late to stop our march to authoritarianism. But it is still worth the effort to resist.

Chapter One:

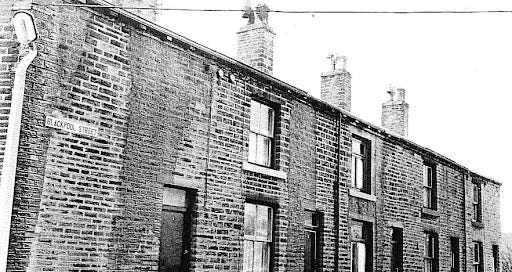

I was born in a Barnsley slum on February 25th during the economically bleak winter of 1923. My working-class family were on a first-name basis with poverty and hunger. So, my beginnings weren’t auspicious but damning.

The start to my impecunious rough and ready life was the way it was for the working class during the first quarter of the 20th century. From my first breath of life outside of the womb and all subsequent breaths during childhood; my belly would never be full because I was the bairn of a Yorkshire miner.

Working at the coal face was what my folk had done since the Industrial Revolution. Before then, my ancestors mined tin. For generations, we were brute labour for the mucks who lived in stately homes. That's capitalism for you- to the many miseries and to the few wealth beyond imagination.

Had The Great Depression and the Second World War not revolutionised my working-class world, I too would have earned my crust by hacking coal from Yorkshire’s sunless underworld.

But when I came into existence in 1923 that was a distant future that was hoped for and dreamed. It was something imagined whilst one sat in the tepid water of a tin bathtub hastily opened up in a dank, cramped kitchen on a Saturday night.

In the year of my birth, the only certainty for my people, the workers, was toil without end. The only thing guaranteed to us was to labour, at jobs that never paid enough to afford satisfaction, purpose and pleasure while on this mortal coil.

1923 was a fearful, unstable, and melancholic time to come into existence. Grief over the dead from the First Great War was still as sharp as broken glass. The memories from that time of mass murder were as fresh as the scent from a grave dug in the morning to someone who strolls a cemetery in the tea time light of evening. A hundred million soldiers, mostly workers from the nations of Europe, were slaughtered from 1914-1918. The entitled said all those battles waged, whether- they were great or small ensured that the world would be forever more at peace. It was a bunch of bollocks and cold comfort to those who mourned their dead from that conflict.

The soldiers died for nothing except the vanity of the monarchs who ruled Europe during that era and the greed of their munition makers. The coal barons, steel merchants, uniform makers, shipbuilders, stock brokers, and bankers all made a pretty penny helping to crank the handle of the meat grinder called the Western Front. What did the soldier get a grave, or if they survived a body mutilated by gas, bombardment, bayonette or bullet.

When the guns went dumb and the killing stopped, peace was supposed to turn swords into ploughshares. But instead, a pestilence fell across the former battlefronts and home fronts.

Over 60 million people died in this plague known as the Spanish Flu. The virus was a modern-day Black Death, and it collected the living and put them in their graves with medieval haste. It brought death everywhere in the world, including Yorkshire.

Then in 1922; it petered out like a forest fire that burnt down all the trees.

So much, death, disease, poverty and despair awaited me once I emerged from the birth canal.

It is little wonder why my mother was in labour with me for hours. I just didn’t want to budge from my safe harbour inside her womb. I did not want to be greeted by a world of threats, harm, and caution.

I would not be coaxed out with either gentle words or harsh curses. Eventually, during the early morning hours, I emerged born into this world while a freezing rainstorm pelted the window of my parent’s dingy front parlour.

I let all around me know I wasn’t pleased to have arrived. I hollered at the top of my lungs after a midwife, who loved gin and cigarettes made from shag tobacco, slapped my arse. I mewled like a runt of the litter for milk from my Mum’s breast because I was underweight.

Being born malnourished was normal for my class in 1923. No matter how hard my dad laboured below in the pits, he never earned enough money to pay the rent and feed his kind. He was capitalism’s beast of burden and treated accordingly.

In the year of my birth, my parents were new settlers to Barnsley. They had come to this spot of Yorkshire because the pits here promised a better wage than up in Wakefield and Barley Hole, where my dad had hewed coal since he was a boy of twelve. Besides, Barnsley was far enough away from my dad’s siblings, who despised my mother and ostracised him for marrying her.

Long after Dad was cut adrift from my family, Mum revealed my father’s family were more than colliers. They were “better folk”, according to her. My dad- she said in acrimonious moments, had let his family’s pub slip through his hands. “It could have kept us in clover until we all breathed our last.”

On the day of my birth, my father was not glad-handed down at his local by neighbours in our village of Hoyland Common. No one slapped his back or shook his hand in congratulations because when I was born, Dad was in his late fifties, and Mum was 27 years his junior. They should have never met, let alone wed and in another era- they most likely never would have.

Dad was the son of a miner/ innkeeper for a public house that stood on the fringe of a colliery in the decrepit village of Barley Hole. It was in the nether regions between Sheffield and Barnsley.

My parents were first introduced to each other - at a Methodist church funeral in Wentworth because my mum's family the Deans, and my father's were connected through a a marriage between relations a generation before in that village.

Dad had the gift of the gab and boundless optimism which seemed enough, along with his family's pub tenancy for my mother to enter a relationship with him.

My mother married my father in June of that year, on the day the Arch-Duke of Austria was assassinated. In 1951, my Aunt Alice said two wars were initiated on that day- the Great War and my mum's war for survival because she quickly learned the truth about the adage: Marry in haste, repent in leisure.

But my Mum’s dreams for financial stability were as hopeful as believing a sandcastle would stand after the eventide comes ashore.

My father didn’t inherit the publican license after Granddad died. Instead, it transferred over to his uncle Larrat ensuring Dad would die a miner rather than a business owner. The machinations Larrat employed to accomplish this were as pernicious and preposterous as any subplot from a Dicken’s novel or at least that is how it seemed to me when my mother during my youth ranted about our “lost legacy.”

After my grandad died my parents moved on from Barley Hole. All my dad took from the pub was a painted portrait of his father, and an upright piano.

According to Mum, bad luck followed our family with the persistence of a stray dog looking for an owner because of Dad’s tender heart. He wasn’t “tough enough, for this life.” Poor Dad was the toughest of us all. He took the misfortunes that came his way after my birth with stoicism and good humour. Sadly, including me, none of his family recognised his heroism because we were too busy trying to escape the economic and socially destructive forces unleashed by the Great Depression.

Nine years passed from the time of my parent’s marriage to my wails of life. The intervening time was a series of disappointments and defeats for my parents. Their relationship in 1923 was shorn of its lustre. Mum was only twenty-eight, but she felt like a broad mare when I was born having already given birth to my two elder sisters, Marion in 1915 and Alberta in 1920. As for Dad, he was in his fifties and his physical strength was in decline. His ability to earn a living to keep us out of the poor house was less certain as he grew older.

The worry, the daily struggle to stretch Dad’s impecunious wages to both make the rent and put food on the table had by the time of my birth worn my mother down to a nub of anger, outrage and cunning. She spent her waking hours outwitting the calamities of debt collectors knocking on our front door looking for the week's rent.

Trying to keep one step ahead of our debts tired Mum out. But what exhausted my mother most was her ongoing row with the grim reaper who since 1920 had tried to steal my eldest sister Marion away from our family.

Poor Marion, drew a very short straw when she developed spinal tuberculosis at the age of five. It was a death sentence for the poor whilst those from the middle classes generally survived their encounter with this form of tuberculosis.

My mother blamed her brother Eddie for giving Marion TB because he was diagnosed with it in 1916 but didn't tell anyone. While on leave from the army he had come to visit my family and played with Marion despite a noticeable cough. But Eddie died in a Sanitorium in Scarborough in 1918. So, I don't think it was my uncle.

It was more likely that slum living created the conditions for my sister to develop TB.

Mum did everything in her power to forestall my sister’s early reservation with death. However, a mother's love for her child isn't a currency that can be exchanged for proper healthcare in a capitalistic society, unless she has the wealth to back it up. All Mum owned was her grit because she was the wife of a coal miner, which the hospitals of Yorkshire didn't consider legal tender.

Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

I can't wait for the publication of the book. I am old enough to understand exactly the conditions that are explained with in it. It is not just history, its a reminder of what we should ALL be fighting against.

You remember, as my parents did, how life has been. But it could be a whole lot worse (the Tufton Street Tory ambition). We have to resist the slide to fascism, which of course is the strong arm of capitalism. Dietrich Bonhoeffer said, "Hitler is the anti-Christ. Therefore, we must go on with our work and eliminate him whether he is successful or not". That same applies to fascism and its cheerleaders today.