"My family mouldered on capitalism's fallow fields of industry during another cost of living crisis that we called the Great Depression."

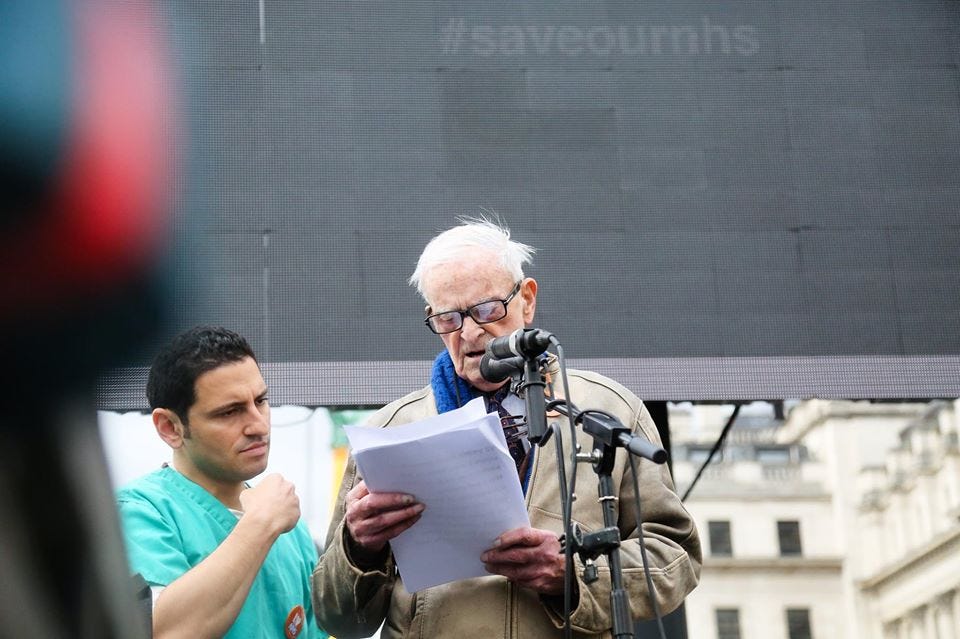

Comrades, go well into Harry Leslie Smith’s Green & Pleasant Land. As promised here is the second instalment of the first 25k words of Harry Leslie Smith’s unfinished manuscript about the Birth of Britain’s Welfare State as seen through his eyes during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Instalments will be dropped everyday this week.

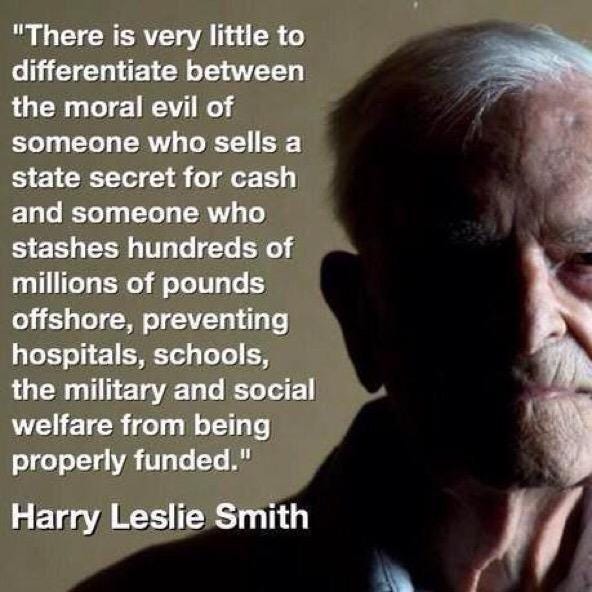

Works like the Green & Pleasant Land are more important now than ever now because people have forgotten their working class past. In 2024 we stepped through the looking glass into fascism. What we are living now will only get worse and it will take more than a generation to change. It will take the grit and the outrage that past generations had who fought to take their lives back from being owned by the entitled.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going and me alive is greatly appreciated. So if you can please subscribe and if you can’t it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury.

Chapter Four

In the Winter of 1928, my family was migratory, little better than beasts of the American plain when drought kills off all their food supply. We couldn't rest. With Dad unemployed, we kept flitting from one temporary accommodation to the next because affordable and habitable housing was hard to come by. With no prospects left to us in Barnsley, we upped sticks for Bradford in the damp dusk of February day.

As we fled, Alberta and I questioned our mother about why we had to leave but were hushed by her.

"This is not a concern for children. Forget Barnsley."

Dad was more sentimental than Mum. He couldn't forget or let go of things, no matter how; superfluous they were to our present circumstances. He took to our new life- mementoes from his past that, in our changed surroundings, pricked him with the sharpness of a thorn. On our journey to Bradford, he carried a portrait of his dad and some books of poetry and history tied together with string.

"Why did you bring that rubbish,” Mum barked as we struggled onto a bus where all the hard wooden seats were already occupied.

In response, Dad said nothing because he had no defence except a belief that things would get brighter for us. Mum refused to let it go.

"You would have taken the bloody piano if it weren't down at pawn shop to pay for the bus tickets."

Mum secured lodgings for us at a doss house in the neighbourhood that now holds that city’s university. In the 1920s a doss house was a last resort for people who struggled to make rent. If you could afford a room in a doss your other alternatives were life on the street or the workhouse. Our rent at this doss was cheaper than other tenants because mum- took on the dubious responsibility of collecting rent from the other lodgers who, like us, were skint.

Mum became an excellent rent collector for the absentee landlord of the doss because Marion's death, Dad's unemployment and her surviving children's hunger hardened her heart against the trials and travails of strangers. On the surface, to the other lodgers, Mum was friendly enough if it got her something. However, underneath Mum's smiles and jokes were sharp daggers ready to plunge into anyone who threatened our survival.

In Edwardian times the doss house we now inhabited was owned by a prosperous middle-class Bradford family. But wealth, hope and prosperity had long ago jogged on from that house and the surrounding neighbourhood. By the time of our arrival, it was a run-down three-storied eyesore. Its foundation had subsided in the ground and gave the house the appearance of a ship taking on water from a gash in its hull.

The other tenants were Irish navvies who slept four to a room on hard cots and sang lewd songs before bed. In other rooms, there were shell-shocked soldiers from the Great War who screamed in their sleep when their dreams led them back, to the Somme and Ypres.

The rest of the lodgings were taken up by indigent pensioners. We rented a small room on the second floor, and in it, we were expected to do our sleeping, eating, and fretting. The privy was outside, and a key near the front door granted one entrance to a bog that made me wince from the foul odours emanating from its hole that seemed as deep as a mine shaft.

The navvies in our doss were tough men who built and repaired the roads around Bradford. They knew how to drink, how to swear and how to brawl. But they were always kind to me, and my sister and they were like butter on toast in my mum's hands because she flirted with them- while Dad became increasingly an insignificant shadow on the wall of our lives.

My father withdrew into himself. He couldn’t tolerate his helplessness as we fell further into rough circumstances. Each morning, following breakfast, to avoid unpleasant questions or demands from Mum, Dad made ready to leave the doss by putting on a worker’s cap and short coat as if preparing to leave for work.

Dad never got out of the door without my mother piercing him with sarcasm.

"Lord Muck, where are you going? There’s work to be done around this house.”

“It must be nice to live the life of the idle, bloody rich and have time to stroll about town.”

I knew, Dad, was doing more than larking about. He was looking for work because he confessed this to me sometimes when bidding me goodnight at bedtime. But there wasn't any on offer for a man who looked and was past his prime.

While my father marched along the rough, unforgiving pavement of Bradford streets, my mother kept order in the doss by ensuring the other residents paid their rent on time. Now, there was more vinegar than honey coursing through Mum's heart. But on occasions, Mum had a great ability for kindness and forgiveness. The lead on her compassion was short as every day was a battle against economic rapids that led to either the workhouse or premature death.

For a while, Mum tried to protect a young man down on his luck who shared digs with a couple of navies. He was shy and not good at surviving. Mum stood up for him when the other navvies took the piss.

But he had a bedwetting problem, and it became chronic. At first, my mother let his bedwetting pass without rebuke because his rent was paid on time. Unfortunately, the young man pissed his bed on one too many occasions. Complaints were made by other occupants in his room because the smell from his soiled clothing and bedding was so strong that it overpowered the cloying stench of their unwashed humanity.

My mother tossed the poor beggar out on his ear like he was a cat in the wrong house. When he pleaded for his possessions; she returned to his former bedroom and from an open window hurled his meagre belongings, along with the piss-stained flock mattress, to the pavement where he stood below.

As books and clothes dropped to the ground, my mother swore at him and warned him never to return.

“Oi piss pants, bugger off home to your mam and stay out of my bloody way or I’ll give you such a bollocking, you’ll have a reason to wet the bed.”

There was always noise in the doss. Doors slammed, people farted and belched, cursed, wept, and even laughed into hysteria. Dad was the only one who was quiet about his fate. He was exhausted by his daily walking and search for work.

In the evening, after our tea of porridge or boiled potatoes, he sat on a stool by our fireplace grate empty of coal- and chewed on a pipe starved of tobacco.

On the wall above Dad was the elegant portrait of my granddad, the publican who, in the painting, sported a giant handlebar moustache and wore the accoutrements of modest prosperity.

On that grimy wall stained from years of smoke and cooking fumes whose paint was flecked in the colour of grit, the portrait of my grandad stared down at us as an incongruous image of propriety. If I upset her, my sister would say in mockery,

“Look up, granddad is cross with thee."

Most evenings Mum absented herself from our quarters until it was time to sleep. She preferred being downstairs in the common room in the company of the navvies. There, she flirted, joked, and schemed for a way; she and her children could escape our plunge into poverty. Dad, by this time, was not included in Mum's escape plans because he was a dead weight to her. She now looked for a means to jettison him from our lives.

If Dad knew he was being erased from our existence, he didn't protest or let on. Dad continued, as he had done through all our trials in Barnsley, with stoic optimism and making amends for our shabby existence as best he could with the limited resources available.

On occasion he allowed me to leaf through one of the few things he still owned and cherished- Harmsworth's History of the World in eight volumes. These books were bound in leather, embossed with gold leaf, and stood in a neat row on top of an old and wobbling table.

When I was allowed to open them, I saw magnificent illustrations, exact drawings of faraway places and unheard-of kingdoms. I lost myself in The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. I dreamed I was before the mighty Pyramids of Egypt and forgot the noise of tenants below or the brash orders from my mother that seeped up through the floorboards. I was not there anymore because my imagination had taken me to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which soared seventy-five feet above the ground, flush with a bounty of flowers. Other times, I was at the Temple of Diana, or the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus because the pictures and words in those history books made me feel a million miles from the doss house and our cramped room.

After one of my excursions through the ancient lands found in the books of Harmworth's Histories, my dad said-

“One day, lad, you will go out into the world and see some fantastic, magical places; I never saw.”

"Can we go together?"

He did not respond. Dad just put his pipe bereft of tobacco between his lips sucked on it, and remembered when he could afford to smoke.

Chapter Five:

Humans are hardwired to keep hope alive and believe that tomorrow can be better than today. For the poor, it seldom is because when there is no social safety net; your poverty can't be outrun. It doesn't stop people from trying. Mum tried to slip her chains of poverty. She married my father because she wanted to believe he could supply a better life for her. Instead, their marriage put both of them on a quick road to penury. Then, in 1928, after my father lost his job in the mines because of injury; she upped sticks with him and my sister and me for Bradford. She wanted to believe new beginnings were possible for those without money or work. But it was the same old..

In Bradford, like Barnsley, no one wanted to hire my father for work because he didn't look physically up to a day's manual labour owing to his age.

During our first year in the city, we subsisted on poor relief- provided by the local council. It afforded us enough for the barest of food rations- so as not to starve but not to eat nutritiously.

Being underfed created a host of physical symptoms for me and my sister, which included leg ulcers and boils that erupted on my body. These afflictions were commonplace in our neighbourhood- along with lice, rickets and TB.

In 1929, when the world's stock market crashed, neither my family nor the other residents of the slum we lived in understood that the greed of middle-class speculators combined with an unregulated- corrupt banking industry would wreak more havoc on our lives and society than the first world war had done.

Britain's working class thought when they elected a Labour government in May of 1929, they had bought insurance against the avariciousness of the entitled and their indifference to the living conditions of ordinary citizens. How wrong they were because it was a Labour government that sacrificed the well-being of millions of workers to the harshness of the Great Depression by implementing austerity measures that were as cruel as any Tory government before them.

The government abandoned the working class to a dole that paid an amount which guaranteed famine for the recipient. After the mines closed, the textile factories powered down, and factories shuttered as the world's economy shrank, millions of men were wage-less, an army of unemployed. They were abandoned by Ramsey Macdonald's government and left to wither and rot like fruit that had fallen to the ground in autumn. Along with those millions of unemployed, my family mouldered on capitalism's fallow fields of industry.

At the start of 1930, fuel and food were scarce for us and everyone else without work. I still remember my mother on bleak winter mornings reheating for breakfast the porridge we consumed for supper the night before. While she dolloped it out into our bowls, I'd sing.

“Old Mother Hubbard went to the cupboard to give the poor dog a bone. But when she got there the cupboard was bare and so the poor doggie had none.”

Despite my mother securing a reduced rent in the doss, through being a harsh rent collector for its absentee landlord, we still were in arrears. Mum, for a while, charmed the landlord into patience for his money, but not for long.

So, one night before a bailiff came- we slipped from our doss house lodgings and onto unfriendly streets under cold Yorkshire skies.

My mother found us another set of rooms to live in that were more decrepit and stank of other people's sweat and misery. This new residence was in a wretched slum occupied by furtive characters who had given all hope of even the most simple working-class life.

During those days in that brutal neighbourhood, we lived famished from sunup to sundown. Until one day good fortune seemed to shine down upon my family. Mum had gone out to pawn her wedding ring,- and as she walked along Manningham Lane; she spied a leather bag with a chain clasp around it. She picked it up and noticed that it had the name of a department store stencilled across it.

Curious and hungry, she opened it and discovered fifty pounds in notes and silver in the purse. It was a store’s bank purse, and an accounting clerk must have dropped it in the street- while on his way to make their daily deposit. It crossed Mum's mind to pocket the money and not say a word to anyone because fifty pounds was a King’s ransom to a family living on less than a pound a week. However, my mother’s conscience and the knowledge that she was many things but not a thief wore her down.

My mother walked over to the store whose clientele were the well-heeled residents of Bradford who had escaped the misery of the Great Depression. Inside, she spoke with the manager. He was officious and thanked her coldly for her honesty. The manager rewarded my Mum’s good turn with a tin of stale, broken biscuits.

Mum fled the store, ashamed and furious that her honesty had paid her so unjustly. Her good deed was valued by the store’s manager to be worth no more than a tin of broken biscuits in a city where children were dying from hunger.

My mother spent that night in bitter silence She was locked in a hateful glare against the tin of broken biscuits while Dad begged her to come to bed on their flock mattress that lay on the cold floor of our one-room tenancy beside the one my sister and I shared.

The following morning, Mum returned with me to the department store holding the tin of broken biscuits as if was a throttled neck. At the store, she demanded to see the manager. The obsequious attendant asked if the manager would know the reason for her visit.

“He bloody well will."

When the manager appeared, Mum slammed the tin of broken biscuits down on a counter table by the till with so much force it made other customers stop and look for what caused the noise.

“You can take these bloody things back, ”my mother shouted at the manager.

“Back? But why?”

“I found fifty pounds of your money yesterday. You think a few broken biscuits are fair compensation for my kindness to your store?”

The manager arrogantly and dismissively replied, “Yes.”

“Bollocks, my good deed is worth at least five pounds.”

“Five pounds? But that is a lot of money,” the manager told her.

“It’s a lot less than losing fifty pounds.”

“I can’t possibly…” the manager responded with haughty disgust.

“Look,” my mother said, as she pushed up close to the manager’s face. “Give me a just reward, or I am going to scream that you throw crumbs to a poor mother with two little kids to feed and a sick husband to care for.”

The manager was flustered and looked confused that someone so abysmally poor as my mother would demand more than she was given.

He didn’t know what to do. But as other customers in the store took notice of my mum’s outrage, he relented. He gave my Mum four pounds under the condition she never returned.

It was a glorious victory for my mother. For the rest of her life, Mum told anyone willing to hear the story about the day she won against the Toffs.

The money she had wrestled from the store manager for returning their deposit bag kept us fed and housed for two months. From then on, it was clear; that it was my Mum and not my father- who would drag us to safety during the harsh economic times of the 1930s. I would, however, soon learn dragging someone to safety- does not mean they come out of a catastrophe without scars, anger, resentment, or sadness.

Chapter Six:

Over eighty years on, but I still remember 1930 as if I'd bumped into on the street yesterday. You never forget hunger or how people will betray one another for a morsel of food. 1930 was a year of famine for me, my family and working-class Britain. Hunger gnawed at the bonds that held our family together until they tore apart from a desire for self-preservation. My parent's marriage was irreparably sundered in 1930- love cannot be nourished on an empty belly.

My childhood, such as it was, concluded that year as I learned my mother did not have the emotional strength to protect me from- the harsh world- we inhabited.

During an era of economic collapse, nothing lasts, not love, loyalty, or friendship. Kindness was like ballast dropped from a faltering balloon in danger of crashing to the ground.

My mother didn’t set out to abandon my father, but The Great Depression robbed her of the ability to act nobly. By the time we came to living doss house rough, Mum knew our Dad was a dead weight that would drown us all if he was not jettisoned from our lives. In that era, my mother's only hope and mine to escape death by poverty was for her to find a man capable of earning his scratch. The problem was Mum was as bad at picking men as my Uncle Harold was at picking winning horses.

My mother crashed into the orbit of a handsome, quick-talking Irish navvy named O’Sullivan when he arrived as a lodger at our doss house. This navvy liked her too, or at least the prospect of wooing my Mum into bed. He lavished her with compliments, jokes, and flirtation.

O'Sullivan carried himself like a soldier and was sure of himself. The economic crash hadn’t stolen his sense of self-worth. Confidence was- an aphrodisiac for Mum, who had lost hers after too many midnight flits.

O’Sullivan made Mum smile and laugh, and despite my early age, I knew she liked him more than she should. Sometimes, she didn’t come back to sleep in our room at night, and there were whispers from other lodgers about the sin of fornication.

For Mum, O’Sullivan’s attentions were like a life preserver thrown to a drowning person. She reciprocated his affections and longed to be with him. She resented the time spent in my father's company and became more acerbic and cruel to him.

Nightly under the spluttering glow of our one gas light that was bolted onto a greasy wall, my Mum cursed my Dad for leading her into a life of harsh poverty. Dad did not fight back but instead apologised for his age, infirmities and the things that were not his fault. Mum was never sated by his acceptance of guilt because Dad saying sorry was not enough for her. Mum resented my father because she was the one who begged, borrowed, and stole to ensure that my sister and I had some morsel of food for our tea each night. Mum was the one who went to charity shops and pleaded for clothing for me and Alberta.

Mum was the one who obtained for me the worn corduroy trousers that were stained with the piss from its former owner at the St Vincent De Paul mission.

If anyone dared to question any of her decisions that affected our entire family, Mum responded.

“I am the one who eats the shit for thee.”

Mum fell in love with O'Sullivan because it was an escape from the reality of her existence. It was a fantasy more than anything else. Yet, it had horrible consequences for everyone but O’Sullivan. My mother deluded herself into believing a new life could be at hand for her and her kids with this attractive young workman who promised her a life of plenty down south. She ignored the reality she was already married to my father, who, although disabled, was very much alive.

In the 1930s, working-class women rarely obtained a divorce because of the cost and the moral hypocrisy of that era. Facts, however, didn’t stop my mum, and she did all that she could to make herself become more than a fling to O’Sullivan.

Although she went about it most peculiarly because her Irish lover didn’t seem to my childish eyes to be a man of any faith, save for that of self-preservation and taking, damn the consequences, what he could from others.

It got into Mum’s head that if her children were the religion of her lover, it might be easier to pass us all off as a family unit. My mother was plotting ahead and reasoned that my dad could be abandoned- while she, Alberta and I would live with O’Sullivan outside of Yorkshire as a pretend family. To aid in this fiction, my mother had me and my sister converted to Catholicism whilst she a sinner, stayed far away from any confessional box.

Yet it was not just lust that drove my mum to embrace the Church of Rome. Mum had heard that the catholic church in Bradford provided better food parcels than the Church of England.

I remember my first day at catholic school and being terrified by the priests whose faces were whisky-red from too many nights of cards and cigarettes. I soon learned it was not the priests you should fear but the nuns who taught me my catechism.

Sister Christine was the nun I learned to fear more than anything else because she seemed charged by God himself to deliver his wrath against me. Sister Christine was a dour, unhappy character who took no joy in beauty or in children.

One day at school, the Sister instructed our class to draw an apple that sat on a table. Like a creeping Jesus, the Sister moved around the room on rubber-soled shoes to inspect the drawing prowess of each student as if she were a judge at an art competition. When Sister Christine came and inspected my drawing of the apple, she was not pleased. The nun said with disgust. It was sloppy, smudged an insult to her and God. Not satisfied with verbal barbs, the Sister so outraged by my drawing, struck me with a strap across my forehead. The strength and ferocity of the blow made me black out for a moment. When I came to, I wept in pain, fear, and humiliation.

When I returned home from school, my mother noticed the bruised whelp on my forehead. It outraged her that a stranger dared to physically punish a child of hers. Mum would have her retribution and went to school with me the following morning to confront Sister Christine about my beating.

“I hear you’ve been disciplining our Harry for not meeting your fancy apple approval.”

“Sister, mark my words, touch my boy again; I will beat you black and blue with my very hands.”

Upon leaving, my mother said to the nun, whose mouth was agape in surprise and fear, “Justice is mine sayeth the lord.”

*********

As my mother's flirtations with O'Sullivan became more overt my dad became more distant. He didn't have it in him to fight anymore for himself or his family. He drifted between taking long walks to avoid my mother's wrath and when home reading books of history and poetry underneath a sputtering gas light in our rented room during the evenings. He tried as best as he could to be my father. He even for my birthday in 1930, found a few spare pennies- and took me to the Alhambra Theatre to watch a pantomime of Humpty Dumpty. He could only afford the cheapest seats, which were high up in the theatre.

While we climbed to them, he said, "Mind you don't bump your head on a nearby cloud." But I didn't care. I had never been to the theatre, and I was just thrilled to be in the company of my father. When the performance was over, I felt I'd been touched by magic. However, that feeling of exaltation didn't last long.

My joy from that afternoon matinee was quickly dissipated by witnessing my parent's marriage founder on the sharp rocks of poverty, infidelity, and mutual recriminations.

My mother's affair with Mr O'Sullivan caused extreme discord within our family. There were arguments, yelling, and hurtful things said to each other, but never any physical violence. Mum was desperate for love, for an escape from our poverty. She blamed my father for our circumstances and berated him in front of me.

After my birthday, something snapped in Mum, and she concluded enough was enough for her. She deluded herself into believing that O'Sullivan could save her and her children from the Dickensian poverty we lived in and ran away with him to start a new life. Mum believed all things in her life could be fixed if she ran off with O'Sullivan.

My mum fled south with O'Sullivan because he had friends and work available to him in St Albans. They left by train to an England she had never seen before. Mum never read the book. But maybe when the movie version of Anna Karenina came out in 1935, she watched it at the cinema and recalled her desperate escape from Bradford in March of 1930. She might have recognised her own experience of attempting to flee destiny in a third-class carriage that trundled its way to London, she, like Anna, had chosen the wrong man to live in exile with.

My family waited through the early spring for news of my mother, but none came. During that time, my dad, my sister, and I survived on handouts, begging, and sometimes the pity of my mum's relations- who came over to our doss house and paid the arrears on our rent or provided leftover food from their table.

Dad tried to be strong for his children, but what happened to him and us in the year 1930 beat him like a vicious drunk beat their disobedient dog. My father emotionally retreated from his children and the reality of our destitution. On occasion, I found him staring at the grimy walls of the room we lived in, with tears rolling down his face. However, most days, he escaped the world by taking long walks around the city of Bradford or by reading from his eight-volume encyclopaedia of the ancient world. In 1930, outside of my ten-year-old sister's protection, I was alone in the harsh environs of Great Depression Bradford.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John

thank you for your time & effort, i think it is a very important piece of history that ought not to be forgotten.

Beautifully written