I started this Sub Stack in December 2022. I've used it as a means to preserve my Dad's writings as well as the final mission of his life to not make his past our future. My Substack, I hope, is a good place to store and share these writings especially because my health is problematic. I don't expect to die for at least a few more years. But if I go earlier than both me and medical science predict, this sub stack preserves, a personal working-class history of Things Past that may have some utility for others when I am gone.

It's a testament to the worth, uniqueness and profoundness of the lives of ordinary people who are continuously erased from history. It's a worthy endeavour that I am proud of and thankful that all of you have come this far with me on the journey across the shadow lands of the Great Depression and how it shaped the lives and politics of people like my dad. Now more from his Green And Pleasant Land.

Chapter Six

My mother's affair with Mr O'Sullivan caused extreme discord within our family. Between my parents, there were arguments, yelling, and hurtful things said to each other, but never any physical violence. Mum was desperate for love, for an escape from our poverty. She blamed my father for our circumstances and berated him on every occasion possible.

The only time she didn't find fault with him was on my birthday. As a gift, Dad had stashed away some of his poor relief and took me to a pantomime show of Humpty Dumpty at the Alhambra Theatre.

He could only afford the cheapest seats, which were high up in the theatre.

While we climbed up the stairs to our seats, Dad said, "Mind you don't bump your head on a nearby cloud."

I didn't care. I had never been to the theatre. I was thrilled to be there with my Dad. When the performance was over, I felt I was touched by magic. However, that feeling of exaltation didn't last long.

After my birthday, something snapped in Mum, and she concluded enough was enough. She deluded herself into believing that O'Sullivan loved her. She convinced herself that O'Sullivan could save her and her children from our Dickensian poverty. So Mum ran away with him to start a new life down South.

My mother was 35 and had only been as far afield as Leeds from her place of birth Barnsley, until she ran off with O'Sullivan like a doss house Anna Karenina to St Albans.

My family waited through the early spring for news of my mother, but none came. During that time, my dad, my sister, and I survived on handouts, begging and sometimes the pity of my mum's relations who came over to our doss house and paid the arrears on our rent or provided leftover food from their table.

Dad tried to be strong, but what happened to him and us in the year 1930 beat him down and never got back up again. My father emotionally retreated from his children. On occasion, I found him staring at the grimy walls of our room, with tears rolling down his face. However, most days, he escaped the world by taking long walks around the city of Bradford or by reading from his eight-volume encyclopaedia of the ancient world.

The separation from my mother was worse than if she had died. To me, her leaving seemed a voluntary decision.

Dad pretended his wife was on holiday- and we must- make do without her. He didn't know if she was ever coming back. None of us knew if her plans would ever include us again.

My sister Alberta, wise beyond her 10 years and as fierce as a lioness, thought it best after our mum left that I was toughened up. My sister tried to be a surrogate mother to me and an emotional crutch for my dad. It was a horrible burden for a little girl to be forced to bear.

Every night, whilst we snuggled together for warmth at bedtime underneath blankets of old coats, Alberta made plans for us. She'd devise schemes to scoff food from neighbours or where to find something eatable amongst the rubbish in the bins behind Bradford's restaurants on the city's high street. Alberta taught me the ways of a street urchin to ensure I'd always find food to eat. It was strange mothering because Alberta taught me what to look for when we scampered through the rubbish bins outback of restaurants. She instructed me on how to judge like a diamond merchant can spot flaws in a cut gem; what half-eaten chop was rancid and what was fresh enough to eat without becoming sick. She mothered me with affection, harsh words, and sometimes even slaps to keep me alive. We laughed together, stole food together, and during our childhood supported each other emotionally because the adults in our lives were incapable of giving much back because the world had been so unspeakably cruel to them.

She was good at convincing lodgers who were famished themselves to share their bread and drippings with us. My sister taught me to sing songs like Danny Boy to ensure we paid for what we were given.

When my mother left us, The Great Depression had completed its first full year. Industries of the north: coal, steel, and textiles, were in a state of collapse. Like falling fruit to the ground, Yorkshire, in 1930, withered and rotted. Britain's unemployment rate exploded to 2.5 million workers, who were allotted a dole for fifteen weeks. It was substandard government assistance; afterwards, they went hungry, or their kids learned to rummage through the rubbish bins of their towns as I did.

In Bradford and other Northern towns and villages, the effects of malnutrition began to creep across every street corner. Rickets, TB, and death from starvation were not freak occurrences but living experiences for the working class. Disease was rife in all the towns across the poverty-racked North. Early death was considered normal for the working class because healthcare was private.

Alberta and I, followed by other children, chanted down squalid streets blanketed in want and hopelessness-

“Mother, Mother, take me home from the convalescent home.

I’ve been here a month or two, and now I’d like to die near you.”

When my mother left us I felt a deep sense of abandonment. It was heartbreak, I experienced but it also developed in me a deep distrust that anyone could protect me and that love was never absolute. I learned too young that others will betray you: for love, money, weakness and ideologies.

It was an emotionally sunless landscape when Mother ran away. I didn't confide in anyone, my fears, and my terrors outside of Alberta. I knew not to trust others because them knowing my mother had done a runner would put my sister and me in further jeopardy.

Neither I nor Alberta told the nuns our mum had gone for a prolonged naughty weekend. As for the priest at confession, we kept schtum because my greatest fear wasn't an eternity in hellfire for lying to God, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit but having the state put my sister and me into a foundling home.

My family had slipped beneath the waves and were lost because not the government, society, not even more affluent members from my dad's side of the family were prepared to rescue us. We were transient players on this mortal coil destined to be ground into nothingness by the pestle of capitalism and the greedy hands that turned it.

That year when I reached my seventh year of life, I had neither the time, the skill set or a full belly to do my schoolwork. I fell behind the rest of my classmates in arithmetic, history, and grammar. The nuns were unforgiving to those who did not know their assigned lessons. Despite my mother's threats earlier on in the term to punish those who punished me, I was slapped, strapped, or humiliated with harsh words of "dummy, stupid" and "imbecile" by nuns whose stomachs bulged impregnated from over-proportioned meals provided by the alms of Bradford's poor catholic brethren.

And then one day, Mum returned as if she had never been gone from us. She came back into our lives as if she just popped down to the shops for a loaf of bread. She wanted our reaction to her return to be as if it was a working-class, Winter Tale. But it wasn't a fairy tale made right but another chapter in our family’s nightmare.

There, absent for so long, was Mum standing at the entrance to our room in the doss house. She wore a floral dress that sparkled against the decades of grime and grease on our walls. She held a pineapple in one hand as if she had just arrived home from Captain Cooke’s expedition to the South Seas. On the other, my mum carried “authentic Irish soda bread.”

My father looked at her, his mouth agape, speechless at her return.

That night Mum made our tea and confessed as we silently ate the soda bread dipped into a weak meatless broth that she was pregnant. My father was more distant than normal at that meal and for days onward as he was processing in his 19th-century brain his cuckolding. As for the pineapple, Mum showed it around to the other lodgers to demonstrate the wonders and oddities available to the residents of London.

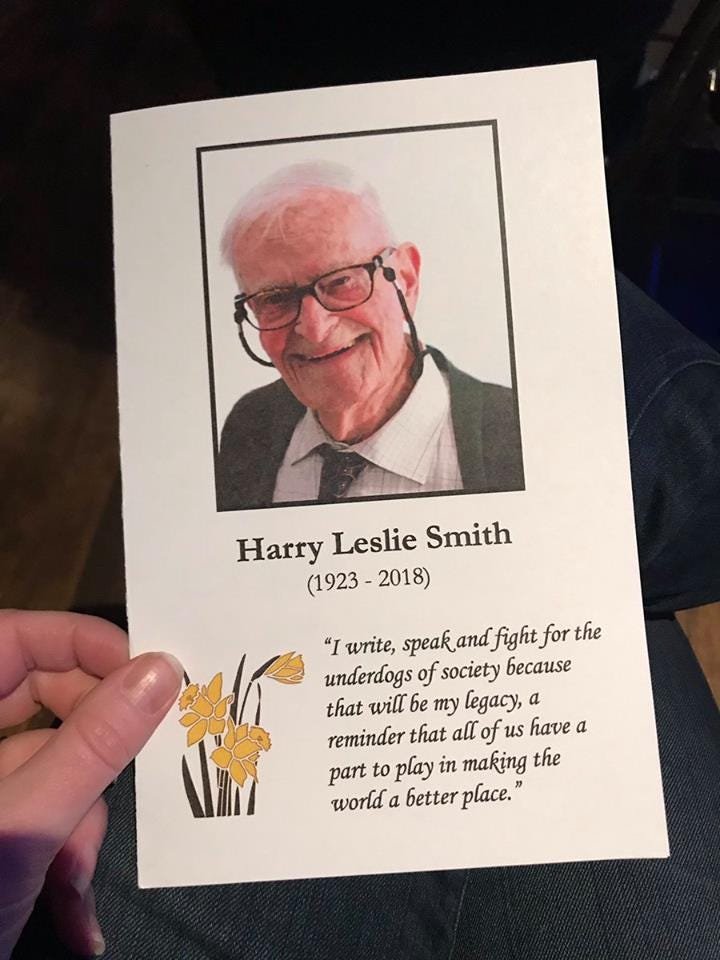

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

I want to see this on Netflix! You've got me hooked on what's going to happen next. It's got all the right ingredients, and is a parable for exactly what neoliberal economics has returned us to.