Neoliberalism created another lost generation. Chapters from the Green & Pleasant Land

Neoliberalism has created another lost generation. This one will never be found because our politics were broken by corruption the way stage four cancer eats away at the vital organs of an afflicted patient. For me, it makes preserving the life history of my father and his generation who lost their youth to capitalism corrupted by greed in the 1930s and then battling the forces of fascism on the battlegrounds of Europe in the 1940s, so important.

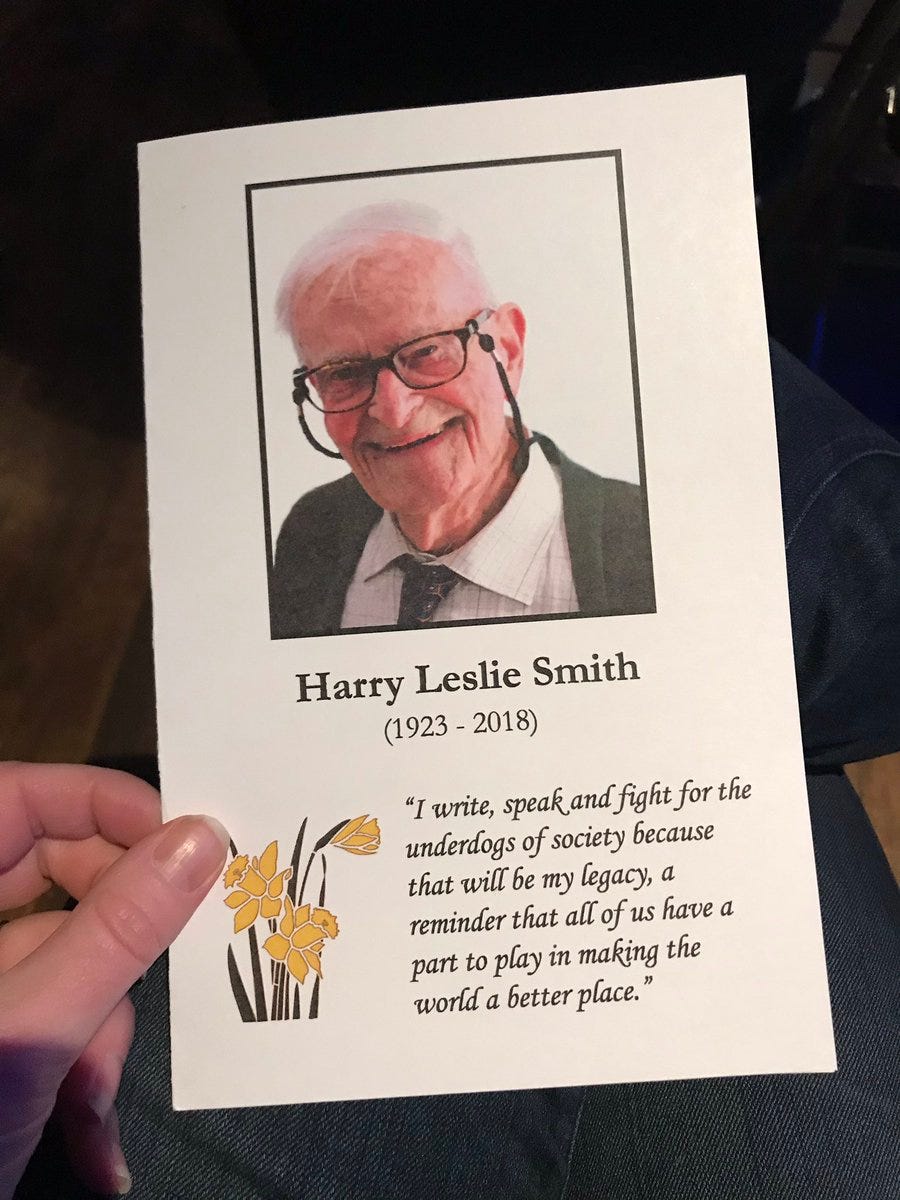

I am navigating all the excerpts from The Green And Pleasant Land to a subfolder on my Harry's Last Stand Substack. It will be easier for readers to find the progression of the last book Harry Leslie Smith worked on before his death in November 2018. I have been editing and shaping it to how my Dad wanted it presented to his readers.

Reading a chapter here or there doesn't give the full breadth of despair and desperation endured by the working class during the Great Depression.

The book is an intimate look at poverty. My father learned first-hand how destitution dissolves a family's love for each other with the harshness of acid touching human skin. It's a political testament of outrage about the lost potential of the working class, who then- like now were chained to lives of hungry drudgery.

The Green & Pleasant Land is important to read at this juncture in our history. Society is broken. Democracy does not function as it was intended. The system is not a for and by-the-people institution anymore. It works for the select entitled few. It can't be repaired, unless we rebuild a Welfare State fit for the 21st century. Democracy won't survive neoliberalism, and should we continue on this path- most of us will envy the dead.

The Green & Pleasant Land

Chapter Seven:

The separation from my mother was worse than if she had died. To me, her leaving seemed a voluntary decision.

Dad pretended his wife was on holiday- and we must make do without her for a brief time. How long that time was a changing schedule with him because he didn't know if she was ever coming back at all. Sometimes, it was "Your mum will be home tomorrow"- other times, "She'll be home next week." None of us knew if her plans would ever include us, again.

My sister Alberta wise beyond her 10 years and as fierce as a lioness, thought it best after our mum left that I was toughened up. My sister tried to be a surrogate mother to me and an emotional crutch for my dad. It was a horrible burden for a little girl to be forced to bear.

Every night, whilst we snuggled together for warmth at bedtime underneath blankets of old coats, Alberta made plans for us. She'd devise schemes to scoff food from neighbours or where to find something eatable amongst the rubbish in the bins behind Bradford's restaurants on the city's high street. Alberta taught me the ways of a street urchin to ensure I'd always find food to eat. It was strange mothering because Alberta taught me what to look for when we scampered through the rubbish bins outback of restaurants. She instructed me on how to judge like a diamond merchant can spot flaws in a cut gem; what half-eaten chop was rancid and what was fresh enough to eat without becoming sick. She mothered me with affection, harsh words, and sometimes even slaps to keep me alive. We laughed together, stole food together, and during our childhood supported each other emotionally because the adults in our lives were incapable of giving much back because the world had been so unspeakably cruel to them.

She was good at convincing lodgers who were famished themselves to share their bread and drippings with us. My sister taught me to sing songs like Danny Boy to ensure that we paid for what we were given.

When my mother left us, The Great Depression was in its second year, and industries of the north: coal, steel, and textiles, were in a state of collapse. Like falling fruit to the ground, Yorkshire, in 1930, withered and rotted. Britain's unemployment rate exploded to 2.5 million workers, who were allotted a dole for fifteen weeks. It was substandard government assistance; afterwards, they went hungry, or their kids learned to rummage through the rubbish bins of their towns as I did.

In Bradford and other Northern towns and villages, the effects of malnutrition began to creep across every street corner. Rickets, TB, and death from starvation were not freak occurrences but living experiences for the working class. Disease was rife in all the towns across the poverty-racked North. Early death was considered normal for the working class because healthcare was private.

Alberta and I, followed by other children, chanted down squalid streets blanketed in want and hopelessness-

“Mother, Mother, take me home from the convalescent home.

I’ve been here a month or two, and now I’d like to die near you.”

When my mother left us I felt a deep sense of abandonment. It was heartbreak, I experienced but it also developed in me a deep distrust that anyone could protect me and that love was never absolute. I learned too young that others will betray you: for love, money, weakness and ideologies.

It was an emotionally sunless landscape when Mother ran away. I didn't confide in anyone, my fears, and my terrors outside of Alberta. I knew not to trust others because them knowing my mother had done a runner would put my sister and me in further jeopardy.

Neither I nor Alberta told the nuns our mum had gone for a prolonged naughty weekend. As for the priest at confession, we kept schtum because my greatest fear wasn't an eternity in hellfire for lying to God, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit but having the state put my sister and me into a foundling home.

My family had slipped beneath the waves and were lost because not the government, society, not even more affluent members from my dad's side of the family were prepared to rescue us. We were transient players on this mortal coil destined to be ground into nothingness by the pestle of capitalism and the greedy hands that turned it.

That year when I reached my seventh year of life, I had neither the time, the skill set or a full belly to do my schoolwork. I fell behind the rest of my classmates in arithmetic, history, and grammar. The nuns were unforgiving to those who did not know their assigned lessons. Despite my mother's threats earlier on in the term to punish those who punished me, I was slapped, strapped, or humiliated with harsh words of "dummy, stupid" and "imbecile" by nuns whose stomachs bulged impregnated from over-proportioned meals provided by the alms of Bradford's poor catholic brethren.

And then one day, Mum returned as if she had never been gone from us. She came back into our lives as if she just popped down to the shops for a loaf of bread. She wanted our reaction to her return to be as if it was a working-class, Winter Tale. But it wasn't a fairy tale made right but another chapter in our family’s nightmare.

There, absent for so long, was Mum standing at the entrance to our room in the doss house. She wore a floral dress that sparkled against the decades of grime and grease on our walls. She held a pineapple in one hand as if she had just arrived home from Captain Cooke’s expedition to the South Seas. Whilst in the other, my mum carried “authentic Irish soda bread.”

My father looked at her, his mouth agape, speechless at her return and the condition she returned to us in. She was changed. Soon, we would learn how changed you had become down south by O’Sullivan’s doing.

That night Mum made our tea and confessed as we silently ate the soda bread dipped into a weak meatless broth that she was pregnant. My father was more distant than normal at that meal and for days onward as he was processing in his 19th-century brain his cuckolding. As for the pineapple, my mother never offered it to us to eat. Instead, my mum showed it around to the other lodgers to demonstrate the wonders and oddities available to the residents of London.

Chapter Eight:

Home, spurned by O'Sullivan and pregnant with his child, Mum was in a sorry state. She returned to the doss with the same air about her as a captured prisoner marched back to their cell. First, there was initial bravado. Quickly followed by dour silence after she began to contemplate a life sentence behind the four grim walls of poverty.

No one took pity on her- either in our family or the outside world. Instead, the neighbours put two and two together about the reason for her long absence from the doss that coincided with O'Sullivan's sudden disappearance.

Once her pregnancy began to show, they tittered about "naughty weekends"- and then Scarlett lettered my mother- whilst making cruel jokes about my father "leaving the back gate open".

You can't stop gossip, and you can't stop people poking their noses where they shouldn't go. Everyone had to have a whiff of my family's troubles to pretend to themselves their own lives didn't reek as much of squalor, disappointment, and loneliness.

Near Mum's death, forty years after her tryst with O'Sullivan, she confessed the bolt down south in the winter of 1930 was because the "navvy had got me in the family way." My mother hoped a new life could be forged on the outskirts of London from the ash leavings from her one up north.

It didn't work out because nothing ever does for the poor. O'Sullivan was as bad at holding a job as my father was at finding one. Naturally, that led to arguments and the cooling of their mutual desire for each other.

In the 1960s, when all my mum's passions were spent except self-recriminations, she admitted to a sister that O'Sullivan's affections for her were "unsteady." Any love or loyalty O'Sullivan might have had for my mum did a runner at the prospect of responsibility for her and his child. The notion that his wages earned from the sweat of his brow couldn't be used for craic down at the pub because he'd helped make a baby was a language he refused to learn.

Like all her pregnancies, it wasn't a joyful time for Mum. In the precarious age of want that was my mother's time, a baby was just another mouth to feed in a household of hungry, underfed mouths. It was made worse because my father was shamed and humiliated by her affair with O'Sullivan. He resented Mum and despised himself. As for the child growing inside my mother's womb, he didn't hate it, but he didn't like it either.

Nightly, a dense fug of acrimony from screaming bouts between my parents hung heavy in the air of our squat doss house room. My parents raged at each other from teatime until bedtime. They cursed each other about being a jobless husband or a wanton wife. The din from them was so loud, and persistent neighbours pounded on our walls for my parents to "pack it in."

Even as I approach the last breaths of my life, the roar of outrage, fear, and desperation my parents expelled when they awakened in 1930 to the reality their existence was doomed to perpetual unhappiness crashes about in my skull like heavy surf during a storm.

There was no love, trust, or hope left between them, only animosity. Their sixteen years of marriage were based upon a belief; that things could work out and even get better if they just held out long enough for the tide to turn. However, the opposite occurred; the longer they stayed together, the worse things got. Mum knew it couldn't go on that way- for much longer. We were sinking lower and lower into the mire of a poor relief that kept you alive just enough so that you knew how much of existence was an awful losing battle for the unemployed.

To make it out of the Great Depression- one of us had to be forsaken.

Mum chose to save me, Alberta, and herself whilst Dad was to be the one abandoned as if he were excess cargo, on a ship in danger of capsizing. My sister and I didn't have any say in the matter because our mother knew we'd have fought her tooth and nail. So instead, Mum used emotional Dum Dum bullets that she shot into my heart and Alberta's which exploded out a shrapnel of fear that unless we followed her plan, we would have no parents rather than only one.

Mum vocalised what should have remained silent within her adult mind and heart. "It's to the workhouse for thee and thy sister if your dad doesn't find work." At bedtime, I'd close my eyes and wish for sleep to cleanse her words from my imagination. But the feelings the words left in my small boy's imagination never departed. Like Prometheus learned the knowledge of fire, my mum gave me the knowledge, that nothing was secure in this life- and love does not outlast famine.

It terrified me to understand at the age of seven, I was not safe- and could be abandoned, shorn from my family at any moment.

In an age when millions of men were out of work, my mother's only plan to turn her pig's ear, of a life into a silk purse was to find a man, unlike my father, who was employed. To initiate her machinations, we had to leave our current doss. Everyone there knew our family dynamic and working-class misogyny had already pilloried my mother for her dalliance with O'Sullivan and then getting pregnant from him. But since my parents were seemingly still a couple, albeit one, who had a nightly- riotous barny, their outrage was not hot enough to burn my mum at the stake.

The working class in 1930 did not divorce because women were still considered their husbands’ chattel if not by law by social convention. For Mum to openly cuckold Dad would have branded her a whore and an outcast even in Bradford's down-and-out underworld. Any attempt for my mum to attach herself to another man had to be done under the ruse that she was widowed, and my father was not my dad but my mother's.

On the night of our flit when we walked on cat’s paws on streets smeared in gaslight towards our new residence, Dad was quiet. He was surrendered to what we were about to learn Mum had drawn up to be his end.

Mum said my sister and I were for the foundling home if we didn't do as she told us. From now on, our dad was to be called granddad. To not do so guaranteed my sister and me a one-way trip to the workhouse where we would have not even one parent.

Alberta fought a bit against our mother's new directive, whereas I surrendered to it.

I joined this conspiracy and pushed my dad to the periphery of my life when in the company of strangers because I was so fearful of ending up like my sister Marion, who had died in a workhouse. Like that, I let go of someone I loved. I betrayed them and ignored their place in the hierarchy of my affection because someone else I loved said it was necessary to do this to save me and them.

Our new abode on Chesum Street was arid of kindness, and hope burned as low as the sputtering gas light that cast our one-room squat in despairing shadows.

On Chesum Street, we didn't mix or socialise with other doss house residents like in our old slum. It seemed best to keep as far away from them- then let slip that the old man who lived with us was our dad rather than grandad. My only escape from the misery that surrounded me and the lie I told was to forage through the streets of this slum, looking for diversions as a damp summer sun began to unfold itself around Bradford.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. A yearly subscriptions will cover much of next month’s rent. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

This deserves to be a book.