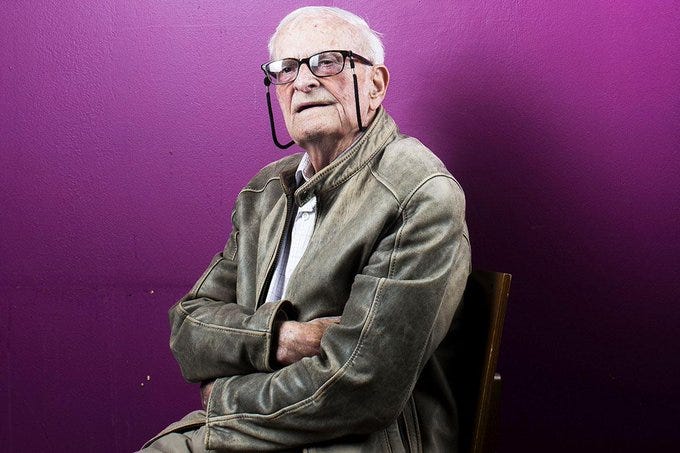

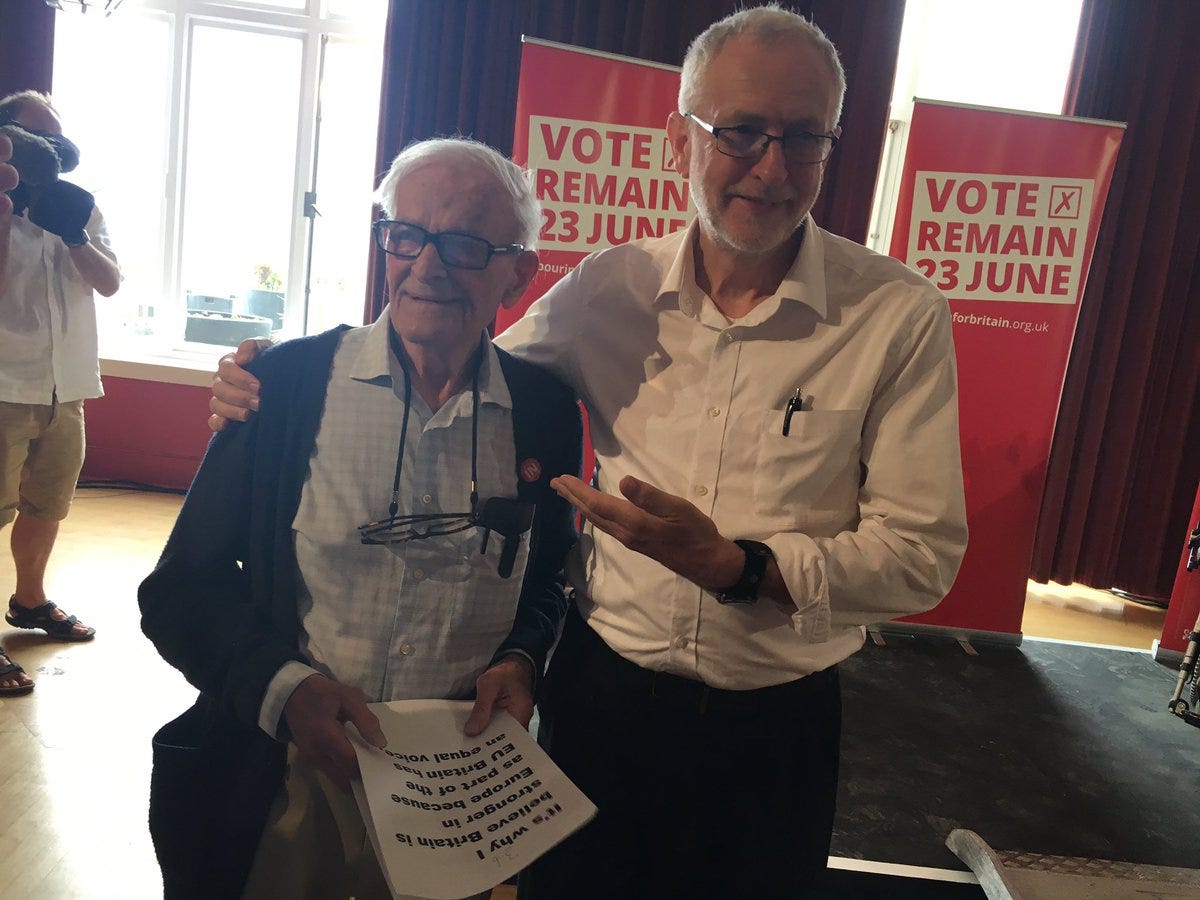

It was December 2022 when I began posting on SubStack. I've used it as a means to preserve my Dad's writings as well as the final mission of his life, which was to not make his past our future.

Sadly, our present-day reality has started to bear a resemblance to his past with a never-ending housing crisis, endemic homelessness coupled with a worsening cost of living crisis. The 1930s should have taught us that declining economic and social conditions make the best potting soil for fascism. But our entitled classes ignored those warnings to improve their bottom lines.

The Green & Pleasant Land was unfinished at the time of my dad’s death.I've been piecing it together from all the written notes, and index cards my father left behind.The whole manuscript will be available by what would have been my Dad's 102nd Birthday on February 25th.

Then after a few final revisions, it will begin its journey to a publisher.

Beta copies will be available next month for any subscriber who wants them.

I am offering a 20% reduction on a yearly subscription to this SubStack because it is four days until rent day. Like every month, I am still scrambling to make the rent payment, especially since it goes up by 5% on the first of February. But, only subscribe or tip if you can afford to. Otherwise, it's all good to be a free subscriber. Your loyalty to me and this Substack is greatly appreciated. I have also added a tip jar for those able, and inclined.

Chapter Thirty-One

St. Athan, Wales, Winter 1942

The train journey from Padgate to St Athan in Wales began in the morning on a note of optimism. But it didn't last. An irritable weariness overtook us as the hours trundled towards nightfall.

When dusk fell and the blackout curtains were drawn across the windows, the men began to gripe and the jokes stopped.

After eighteen hours, our train arrived at Cardiff. The train doors were opened, and we spilt out with the force and sloppiness of water tossed from the bucket of a washerwoman.

On the darkened platform, there was confusion and shouts from NCOs.

"Put that bloody cigarette out. There is a blackout in effect.”

With a kit bag slung on my back, I jumped onto a lorry that took me to RAF St Athan, forty minutes away.

It was the Air Force's best training base for signals, wireless operators, bomb aimers, navigators, and other journeymen who wanted to be in the business of modern warfare. RAF St. Athan was enormous and sprawled across- a vast tract of land as if it were its own municipality whose only industry was war.

Once inside RAF St Athan, we presented our travel documents and assignment orders. Being moved about like a snooker ball irritated Robbie, but it left me unimpressed. I had been banged around and made midnight dashes all through my youth. As a kid, I left many doss houses through the back window or front door in confusion and haste.

At least in the RAF, I knew there was always food and a bed waiting for me.

The mess hut was four times the size of Padgate. The menu was identical; plentiful food rich in meat, spuds, and tea. But it tasted good as we had not eaten since leaving Lancashire.

After I ate, I felt sated. The war, so far, was a piece of cake for me. For others, it wasn't. Europe was a charnel house. The Nazis on the 20th of January had convened the Wansee Conference to coordinate the Final Solution for the Jewish Population across the continent. In the Netherlands and France, their Jewish population were beginning to be deported to labour camps that would eventually become death camps. In Poland, like occupied Russia and Ukraine, the Nazis were reducing populations into a slave workforce. Across Belarus intellectuals, Jews, and communists were routinely rounded up for execution in sparsely populated parts of the countryside. They were shot before enormous open pits where their corpses fell with calculated precision as if they were match sticks being tossed into an ashtray. But no one in Britain knew that yet. We still believed we were in a fair fight rather than a donnybrook with the Devil.

In the morning, I awoke to the barking from a sergeant who bitterly antagonized us to rise from our dark slumbers and make ourselves presentable.

There was no mucking about at St Athan's because Britain was still on the losing end of its war against Hitler.

The airwar was deadly buisiness and the RAF was bleeding men and planes at alarming rates. Bombing raids saw loses of 10 to 30% of its formation from fighter activitiy and from ground anti-aircraft batteries across Nazi occupied Europe.

Bomber Command squadrons took off from airfields all across England and returned in battered formation, their flock thinned and damaged. Death outweighed survival in 1942 for Britain's young who took to the air to defend its islands. Even on the first day at St Athan's, warrant officers encouraged- us new recruits to consider rear gunnery training for active service rather than Morse code signal instructions.

Some took them up right away. But I wasn't convinced dying for the King in this war was the reason for my existence.

Wireless training began on my first day at RAF St Athan.

The instructor was a cynical chain smoker who spoke in precise sentences. He didn't suffer fools or those who were idle in his classroom. We were to learn our new vocation as quickly as possible. So we could get on with our true purpose, fighting the war.

************

Thirty months into the Second World War, battle grounds, on the seas, in the air and on the ground were soaked in my generation’s blood. I knew from the age of four when my sister Marion died that death was horrible, painful and final. There was no coming back from it- and no heaven to enter when life ended. So, I was not about to surrender my life before it had even begun to a King or a country that starved me as a boy forcing me to rummage in rubbish bins for food.

Most of the other young men stationed with me at RAF St Athan were of similar mind to me. There was little enthusiasm for the war in the lower ranks because fighting for a democracy that only promised the working classes, substandard housing, no healthcare and a yearly fortnight's holiday from work at a mill, foundry or coal pit wasn't enough to sacrifice your life for. At St Athan, you heard more loyalty to someone's local football clubs than to Britain or the King.

At St Athan, I was sociable but was reluctant to form close or honest relationships. I was bookish without a formal education which set me apart from others. Liking to read was not thought acceptable working class behaviour.

I was also self-conscious. I felt I had secrets about the harshness of my childhood that I needed to keep buried from others. I feared humiliation because poverty is a shaming experience even if everyone in your class has had their brush with it. Capitalism is like that it makes destitution the fault of human failings rather than a corrupt and greedy system.

If prodded about civilian life. I made it sound as broad and humdrum as possible. I mentioned things about football pitches, pubs, dance halls, cake shops and the pretty girls I knew in the peacetime neighbourhoods of my recent past. I bull-shitted them about my family because my personal tragedies weren't their business, and it was something I wanted to put behind me.

If asked about my family, I invented a narrative that made my upbringing less harsh than it actually was. If someone asked about my father, I said he was dead despite him being very much alive but desperately poor, living alone in a doss house in Bradford. I told them my mother was remarried to Bill, a butcher when she was only his girlfriend because the working classes don't get divorced. I said our family had Sunday roasts and listened to football matches on the wireless.

I wanted the RAF to be my fresh start and a chance to learn a skill that might be useful in civilian life if I survived the war. At least, that is what I told myself and the mates I began to chum around with when we were permitted to go to the village pub on a Saturday night for a piss-up.

Day in and day out at St Athan, my primary ambition was to become so good at Morse code that I wouldn't need to be used as cannon fodder. It was slow, repetitive, and painfully dull progress. But over the weeks, I became proficient in keyboard transmission, signal identification, speed, and message retention.

There was a purpose to this new skill I was acquiring because outside of my classroom, thousands of real messages were being transcribed, sent, and coded each day by a well-trained signals corp.

These messages detailed bombing missions, troop advancement, and endless Bomber Command casualties. They were coded lists of men lost over enemy territory or terse reports about crashed aircraft. They spoke of planes being too shot up to land safely and men dead upon impact.

After, I passed my wireless exam I was granted leave to return home for a few days.

On the day I returned to Halifax; it rained forlornly onto the rough, and worn working-class streets of my youth. Before I went to my mother's house, I had a beer at Halifax's Grandest Hotel, The White Swan.

Outside, the rail station, the newspaper headlines written on chalkboards weren't encouraging. Leningrad was still under a merciless siege. Luftwaffe air raids against Britain were relentless. The war in the desert against Rommel's Panzers was a costly series of battles that left too many men dead on the desert battlefields. We weren't winning the war, and nor was Russia. The Allies were holding the line- but just holding it by their fingernails.

In the sparsely populated White Swan bar room- I savoured a half pint of bitter. The other men along the bar rail, business people, ignored me in my blue serge uniform. They did it with the same ease as when their kind had ignored me when I plied a barrow for Grosvenor's Grocers and wore a worker's cap and coat in peacetime.

The walls of the bar had propaganda posters mounted on the wall.

"Your Courage. Your Cheerfulness. Your Resolution Will Bring US Victory."

Bollocks, I thought.

When the bus dropped me off on Boothtown Road, I walked the rest of the way to my mum's house. I was disappointed no one was about.

I wanted her neighbours to take note that I was in the RAF blue, and they could all get stuff because I was now part of a war machine fighting for their safety.

When my mum saw me at her door; she said sarcastically.

"Look at what the cat's dragged in."

When the kettle was on for tea, my mother informed me that my sister Alberta was doing as well as expected. "Her man did a runner from the army and she's got a wee bairn on her tit."

During the early part of my training, I didn't understand or want to understand the enormity of Alberta's problems. They almost overwhelmed her because Alberta had to raise a child with few resources in wartime, and a deserter for a husband that the police were looking for.

I drank my mum's strong tea in her worn and spartan parlour. My mum complained that there was no sugar for the tea or coal to ward off the dampness because of wartime rationing. As I sipped my cuppa and listened to my mother's complaints and requests that I send her more money from my pay, remorse, affection, and revulsion for her shifted in my heart like an uneven load on the back of a lorry.

I smugly believed that after a few months of keeping in step with the parade Sergeant, I had escaped my childhood and its painful memories.

Coldly, I looked at my mother and thought.

In a day, I'll be gone. And, I won't come back even when this bloody war is done.

My homecoming with my mother was expediently interrupted when Bill arrived home.

“Let’s have a look at you. You did alright, lad. There’s no muck on you, Harry.”

Our sleep that night was disturbed by air raid sirens. But Bill said, There was nowhere to bloody go if a bomb did drop because their street had no nearby shelters.

The all-clear sirens sounded and I went back to sleep.

I visited my sister the following morning, who now lived on Low Moor. On the bus journey to Bradford, there was an endless display of wartime propaganda posters on advertisement boards telling civilians to be vigilant for spies and saboteurs or to conserve food and clothing.

Alberta's house was a one-up and one-down on a hilltop. Around it, the air was thick from the coal fire belching from the rooftops of weaving mills. Until that day, I had never gone to the house she moved to after marrying her husband before I joined the RAF.

The man she married, Charlie, I didn't like. He had an air of violence and drink about him.

I hadn't seen Alberta since my birthday six months previous. The change in her physical appearance was shocking. My sister was anaemic, and underweight- almost a skeleton with skin for clothing. She had lost much of her hair from the stress of police harassment. Local coppers and military police frequently came to my sister's place of work and home harassing Alberta over her husband's disappearance, from the army.

Alberta was reluctant to talk about her life and her husband. And, I was hesitant to speak about my RAF days as I thought it insignificant.

She said.

“You men get all the bloody luck and glory. Look at you in the RAF. It’s a life of adventure, no dull days down at the mill for you.”

At the time, I did not know what she meant. I never fully understood her words until many years later. My sister was far more trapped by the bonds of earth, kith, and kin than I was as a man. Society denied her the right to a well-paying profession and financial independence. There was nowhere for her to run and no bolt hole to hide in until the storms subsided. Even her husband's desertion from the army was considered her sin as much as Charlie’s.

When I left she said.

“If you need something, just holler. I will help.”

I told her the same and then kissed her ashen-coloured cheek.

Sadly, I left knowing that neither of us would call upon the other if we needed help. We both believed, wrongly, that we should not burden each other with our problems.

The next day, I left my mum's house at six in the morning with a terse Tara and caught the train back to St Athan. On board, the carriages overflowed with joking and weary faces of soldiers, sailors, and airmen returning from leave.

Thanks for reading my Substack. You have been great to me. My subscription numbers have grown to 3100 with 223 as paid subscribers.

If you are able. I am rent short and want to remain housed and continue to sustain and grow the legacy of my dad and his Last Stand Project. I think it is worthwhile and necessary. I am looking for 7 new, yearly subscribers to keep the lights on.

It’s 30 quid a year or $50 and I think it has value. Substack and the payment platform take around 20% of that because capitalism is the gift that keeps giving to the wealthy. If you can thanks. If you can’t, it’s all good because we share the same boat.

Take care, John

Your father's piercing observations about the systemic roots of poverty remind me of a Sarah Kendzior quote:

"Poverty is a denial of rights sold as a character flaw".

The entitled classes are the fascists. They have been intent on drawing us back ever since the Spirit of '45 emerged.