Ten years ago, during the 70th anniversary of VE Day, my father Harry Leslie Smith was a hale and hearty 93 year old. The day before that year's commemoration of Nazi Germany's unconditional surrender, Britain held a General Election which Labour resoundingly lost. Labour's defeat set the stage for the Brexit referendum and ultimately the hard right Keir Starmer Labour government of 2025.

Below is a chapter selection from his Don’t Let My Past Be Your Future about the night of that election defeat in 2015 and his reflections on VE Day.

It’s another portrait from my Dad about how neoliberalism was the ultimate betrayal of his generation's blood, sweat and toil exerted to destroy fascism.

I didn’t see the defeat of the Labour Party in the May 2015 general election coming. But it came in the early morning after polling day when most of Britain slumbered. To many on the left, the end came with the same shock as would the unexpected death of a loved one through a car accident on the motorway.

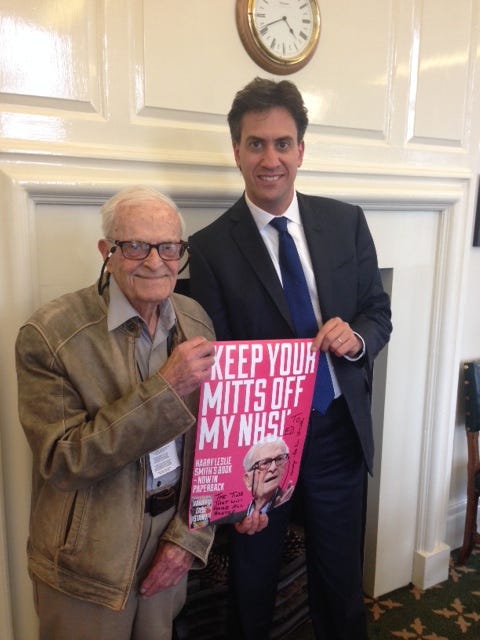

It certainly rattled me when, sometime between 2.00 and 2.20 a.m. on May 8th, political pundits on every network declared Ed Miliband’s ambitions to become the next Prime Minister of Britain dead. I don’t think I’d emotionally invested as much in a general election since 1945. But owing to the hour, the weeks I had spent on the campaign trail, and the speeches I’d given across the country in support of a progressive Labour Party that would protect our NHS from privatisation, I felt at that moment more emptiness than grief.

All I could think was that austerity would be with us forever like a winter that refuses to yield to spring. I felt drained and a fool to have stayed up so late to watch my dreams, and the dreams of millions of others, dashed. I thought to myself that at my age I should have been tucked up in my bed fast asleep but I wasn’t. Instead, I was at a party arranged for Labour Party HQ members to celebrate a victory that never came. I was in the den of a Whitehall wine bar that reminded me more of an air-raid bunker than a boozer. It hadn’t been my first election party that night – I’d gone to several to hopefully feel in that 21st-century crowd that same enthusiasm my generation felt in the summer of 1945 when Labour won that general election.

But it wasn’t to be. By ten o’clock that evening, the exit polls had foretold that Labour’s political fortunes were done. So, when I arrived at this last election party around midnight, the mood among the guests was already lugubrious. The guests’ drunkenness looked both pained and desperate. It was pure and simple disbelief mixed with fear, which bubbled over them and left them disoriented. Neither the drink nor even the late hour allowed anyone in this bar to forget that Labour had lost the election to the Conservatives not by an inch but by a mile. Labour’s defeat was so absolute that even the possibility of a hung parliament evaporated through the night; the Tories won a majority of twelve seats in the House of Commons.

The left and centre, except the Scottish National Party, were savaged by the electorate. The Liberal Democrats were reduced to eight seats as punishment for being either too reluctant or willing to play dance partner to David Cameron’s austerity waltz. Every Labour Party functionary in that wine bar with me was painfully aware that tomorrow and every other day to come for another five years belonged to the Tories and their vision for Britain. Meanwhile, the vote for UKIP on the more extreme right rose from 3.1 per cent to 12.6 per cent since 2010. At the moment of defeat, all around the wine bar Labour workers commiserated in small packs, texting drunkenly, fumbling for words to express a grief writ large by too many sleepless nights and a stomach full of Pinot Grigio. On their faces, flushed with drink and disappointment, I saw the pain of the Labour Party across the many decades of my life: 1951, 1977, 1982, 2010. The style of haircut and clothes might have changed.

But they had the same look of abject sorrow on the faces of those who had put their heart and soul into fighting for ideas they thought would transform our nation for the better.

So it goes, I whispered to myself. But then my heart began to ache for the millions of people who wanted this election to put an end to austerity before it rubbed away their social safety net and their aspirations. It was time to leave what had become a funeral wake at the wine bar and return to my budget hotel. Outside, the air was cool and fresh with the approach of morning.

I breathed it deep into my lungs and remembered how many times I had tasted the sweetness of the early morning. I knew that taste as a lad in Bradford when my family did dead-of-night runners before the landlord seized our scant possessions because of rent arrears. The air then, like on that night of Labour’s loss, was pure. A black cab picked me up and drove me across a London that dozed in the shadow of its somnolent skyscrapers. Those giant buildings of glass and steel stood as silent as clay soldiers entombed in a Chinese emperor’s mausoleum. However, while the city lay recumbent, pundits on LBC spoke like commentators at an FA Cup final.

In caffeinated voices, people said Labour was finished and needed new management and players. Little did I know then how much Labour’s game board would be changed by this election defeat. None of the old guard would be permitted a crack at leadership because of the sheer enormity of defeat. As my black cab floated across the deserted streets of our capital towards King’s Cross and my hotel, I knew this was a turning point for the party I’ve loved since my youth.

I just didn’t realise that it would cause so much upheaval that, two years after the election, Labour’s prospects would be worse than when the votes were tabulated in 2015. I yawned and stared through the taxi window trying to gain some perspective on the night and the long election. I watched the rough sleepers toss and turn on beds made of worn cardboard.

It reminded me of my youth when I saw the derelicts of Barnsley, Bradford and Halifax during the Great Depression, living rough in abandoned buildings like men cast off from civilisation. The homeless on that election night were bathed in an uncomfortable canopy of human-made ambient light. It drifted downwards from empty office buildings and streaked the surrounding dead pavement in a dusky pale afterglow. The rough sleepers seemed to be shadowy spectres from an underworld of the dispossessed. Driving past them, I thought, I hope tonight you have sweet dreams because come the morrow your lives will have just got a little more precarious.

Everyone who had already been dealt a bad hand, in life was now on the thiniest of ice. Come morning, all who have been buggered in Britain by a system that rewards the wealthy and punishes the poor, the vulnerable, the disabled and the disadvantaged would know that the Tories were here to stay for another five years and that they had unfinished business with the civilised state. The result also set the clock running on David Cameron’s manifesto pledge to hold a referendum on our continued membership in the European Union. However, that night no rational person could have believed that, in a little more than a year, the people of Britain would vote for the greatest momentous change in the way our nation does business and interacts with Europe because of an erroneous pledge on the side of a bus that leaving the EU would free up funds for our NHS.

In the dead of night, while the cab sped through amber traffic lights, I felt afraid – not for myself because growing up before the welfare state came into existence had done all the harm it could do me a lifetime ago. No, I feared for all those who just had the simple desire to exist with a decent job, a roof over their head, food in their belly and smiles on their children’s faces.

I couldn’t see how that could be achieved for the ordinary people of Britain. The 2015 general election guaranteed our descent back to the dog-eat-dog world of my youth, when our nation turned its back on the working class and let most fend for themselves in the feral era of the Great Depression. Like then, ordinary folk would suffer under the economic priorities of Cameron’s Tories, who wanted the state to get smaller while the wealth of the few got bigger. Weary, I asked the driver to turn off the radio. Knackered by the early hour, I felt like my hopes for a better Britain with a Labour government had soared past like a rescue plane that hadn’t spotted survivors on a life raft in the middle of the Pacific. I felt utterly alone. I started to feel the wet dabs of self-pity immerse my reason. I couldn’t work out how the opinion polls, which had predicted a minority government for Labour or the Conservatives, could have been so incorrect. But then again, on that night, none of this country’s political gurus understood how our modern-day runes had been so hopelessly wrong – even Paddy Ashdown swore he’d eat his hat if the exit polls were right.

It was so different for my generation in July 1945 because then Britain cast its ballot for a socialist Labour government intent on representing all of Britain, not just its entitled class. But on that night in May 2015, the 1945 election and the optimism it inspired in my generation seemed a long time ago.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith.

For the last 18 months, I've been piecing together my Dad's Green and Pleasant Land, which was unfinished at the time of his death. It covers his life from 1923 to July 1945 concluding with Labour winning the General election. The book at least in its beta form will be ready on May 8th to coincide with the 80th anniversary of Victory in Europe. Let me know if you want a copy.

Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other comorbidities, which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost-of-living, tariff war crisis times. So, if you can, join with a paid subscription, which is just 3.50 a month, or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it is all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

"Free" market capitalism knows, post Mussolini and Hitler, that fascism is very useful indeed as an enforcer. And as historian David Harvey pointed out, neoliberalism was the "grab back" of the ruling class after the brief period of social democracy from 1945 to 1979.