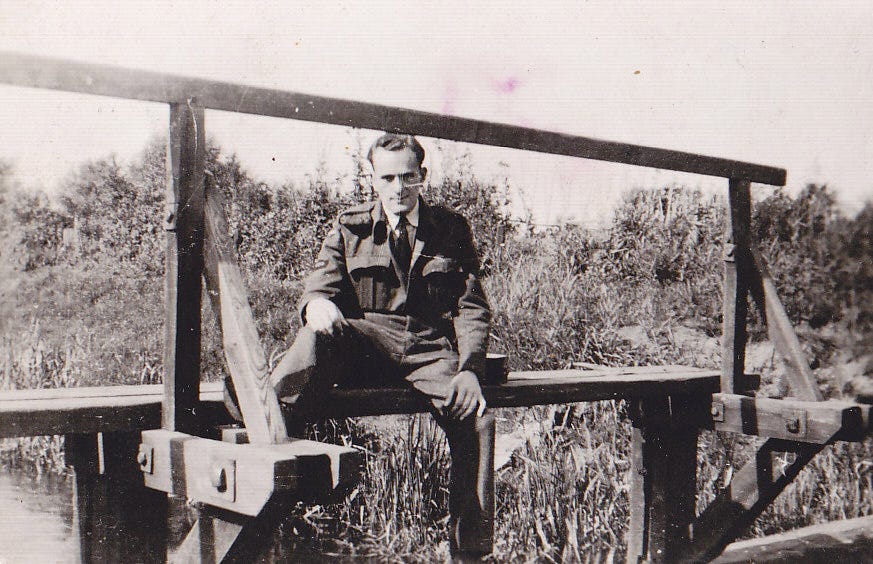

1943 was a watershed year for Britain and my Dad. In today’s excerpt from his Green & Pleasant Land, he deals with aspects of that year, including the death of his Dad.

Before my father died in 2018, he spent the previous decade using the history of his life and working-class contemporaries as a political canvass to paint the dangers of unfettered capitalism for humanity and democracy. He correctly predicted that without a return to socialist politics- fascism and wealth inequality would destroy not just our society but civilisation itself.

His unfinished history- The Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project, along with the 5 other books written during those last years of his life.

For the last year, I have been refining and editing The Green And Pleasant Land to meet my dad’s wishes. Below are more chapter excerpts from it.

I have also included a tip jar for those who are so inclined to assist me in this project.

At the start of the war, RAF Chigwell, in Epping Forest, was utilized to deploy barrage balloons across the London skyline. However, when I arrived in March of 1943, the base's primary purpose was as a conduit for transmitting coded messages about current operations to other RAF installations.

My unit was encamped in tents on a nearby private estate because there weren't enough billets at Chigwell. The property was owned by Sir Felix Cassel, ennobled for being a prominent barrister and a politician, who championed the status quo of empire and class.

During our stay at Chigwell, the only time, my unit marched was when we were presented to the Baronet, who stood at the doorway of his opulent manor home and took our salutes as if we were his feudal lieges.

My unit rarely visited RAF Chigwell and mostly remained on the estate's grounds. We were given few orders except to make ourselves scarce from officers and NCOs. Our only mandatory task was to attend weekly piano concerts performed by Sir Felix Cassel's eccentric son, Francis.

He was born with money rather than any natural talent for music. At his London club, Francis boasted he taught his horses to count to ten backwards in French, and German.

The concerts were performed in a ballroom inside the Baronet's stately home. I had never been into a grand house before then, or for that matter the house of a middle-class person.

Some in the unit felt intimidated listening to classical music in a palatial, private ballroom. We were supposed to be awed by the majesty of our betters, who had leisure to indulge their passions. While we- the workers surrendered our existence to a daily grind that got us nowhere because Britain's economy was rigged to favour the few. Instead of feeling subjugated or overwhelmed by the ostentation of the aristocracy, I felt a great deal of anger towards them. Their wealth was immoral and their refinement was not an indication of being civilised but of their greed and abuse of power.

The concerts made me recall how my dad, with more feeling, banged out Christmas carols on an upright and slightly out-of-tune piano the Christmas after my sister Marion died. Dad's piano was hawked for food after he injured himself at the coal seam in 1928.

At Chigwell sometimes, we slept late. Discipline was so non-existent that once a pay officer came to settle our weekly wages, he found us sleeping off a night of beer drinking.

“Get up, you lazy bastards,” the officer screamed.

The members of my unit played endless games of cards at Chigwell. They played sometimes for an entire month’s wages, which were staked on hands dealt whilst Lady Luck was out powdering her nose. Fortune never sat beside me.

On the only occasion, I was foolish enough to join in and lost half my week’s pay. From then on, I retreated from the mocking aces and gambled my time away reading books.

At Chigwell, I was granted 72 hours leave to visit London. I didn't have a lot of money or many plans. It wasn't a pilgrimage like York had been when I rode my bike at 13 from Halifax to the Minster. Unlike Paris, London had no mythical appeal to me. It was a city of commerce and money rather than poets and revolution.

London was the Big Smoke, where bad things were planned against the people by politicians and the barons of 20th-century capitalism. Still, I went because I wanted to boast to those up North that I had visited the city that turned its back on us during the Great Depression.

When I arrived, the capitol was as defiant as a bankrupt aristocratic dowager winding down her days in a Bristol bedsit. London smelt of stale smoke from a recent air attack. It looked dowdy from rationing. Its inhabitants were irritable from sleepless nights caused by the claxons announcing death was coming for them from above. They were not the Londoners portrayed in the newsreel as cheerfully defiant in the face of bombs, death and deprivations.

It was spring. But the city was as bleak as winter despite bird song in the air because so many buildings were burnt out skeletons.

There was sadness in London because a few weeks earlier, 170 Londoners were crushed to death when they scrambled in panic trying to enter an air-raid shelter because they mistakenly believed the Luftwaffe was overhead them.

I found lodgings in a flop house that rented out beds to be shared with strangers. It was cheap but certainly not cheerful. Bedding together with a stranger on a mattress was how the working class, since the time of Chaucer, lodged when they travelled to other cities, if they had no family nearby.

My bed mate on that first night in London was a wounded airman on medical leave. I was told by the landlady he had no other place to recuperate. She asked me to lend him a hand if there was an air raid because the lad had a broken leg.

She didn't tell me that aside from fractured limbs, his face was badly burned after his Wellington crash-landed upon return from a raid over Germany. The young man, a rear gunner, was caught in the fire when the plane's fuel tanks exploded on impact.

In the morning, I fetched him a cup of tea from the scullery. He thanked me, and then I asked him naively what it was like on bombing missions over enemy territory.

It's a fucking nightmare, and I can't wake up from it.

I didn't stay another night in that doss house. The airman's wounds and words sobered me to the carnage of this war that still hadn't bruised my skin.

In April my unit was ordered back to White Waltham to complete our orientation exercises because we were told when the invasion of Europe came, our unit was to be part of it.

This time, our convoy left at night as they wanted us to become use to front line conditions. Our lorries manoeuvred the roads in the blackout like old men fumbling to take a piss at midnight.

Within a week, we were lost from the convoy. Dejectedly, we set up camp in a farmer’s field three hours from White Waltham. I strung up a makeshift transmission cable across the roof of the lorry. We spent our morning sending out distress messages to our base. We were adrift in England without knowing which direction to turn to.

For the next few months, the RAF divided our time between White Waltham and Chigwell. In the former, we were trained as a mobile transmitter signals unit. In the latter, we were schooled in indolence, sloth, and high culture provided by the imperfect recitals of Sir Fredrick Cassel’s son, Francis.

Despite being told Sicily was our destination my unit was not deployed when the allies invaded the island in the summer of 1943. In the autumn we were also not deployed to the liberated south of Italy. An officer told us our time to leave for Europe was nigh, but no one knew exactly when our zero hour would come.

By October 1943, British troops, including my friend Roy who was in the Cold Stream Guards, had fought there way into Naples and occupied the vanquished Italian port. But I was still in Berkshire. Corsica was liberated by the Free French, and I was still at White Waltham. The RAF made bombing sorties over Hannover, Stuttgart, and Berlin, and my unit was still on mobile communications exercises throughout the home counties.

By this juncture in the war, Bomber Command had lost over five thousand aircraft due to enemy fire. Only 1 in six airmen survived a thirty-mission tour with Bomber Command. The totality and finality of death on land, sea, and in the air war was staggering, humbling, and numbing. I was twenty, in 1943 and my generation was being bled dry to fight Nazism. It had to be worth more than a return to our pre-war dismal, working-class lives that were brutish and unfulfilling.

In December of that year, I received a short letter from my sister Alberta.

“Our Dad died in October. His lungs packed in, Happy Christmas, Love Alberta.”

I read my sister's note several times. It took me awhile to fully comprehend this time my father was dead for real rather than banished from his family and never to be spoken about. I hadn't seen him since 1931 when I was an eight-year-old beer barrow boy. Mum chucked him out then because her lover Bill promised to be a better provider to our family.

News of his death shamed me. I believed I had let him down, not fought hard enough for him to stay with us. I hadn't lifted a finger when he was abandoned by my mother. Mum had her reasons because we wouldn't have made it across and out the other side of the Great Depression if my Dad had stayed with us. Worse, I never went to find him when I became a teenager. I was afraid of who, and what I might find if I got into contact with my Dad again.

I quickly tore the letter up and I went to the pub alone. I did not want anyone to be with me, and besides I had told my mates that my dad was already dead not a lonely doss house lodger in Bradford. So, I got drunk alone at a pub. I wept when I remembered how much my Dad meant to me before he was asked to leave our family. The Innkeeper didn't say anything when he saw me sob. He merely thought I was crying about someone recently lost in the war.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John.

i think this ought to be required as part of the teaching of history, so often all we are taught is the politics & battles, of course it may be nowadays but it certainly was not when i was schooled.