"Society denied my sister the right to a well paying profession and financial independence." Tales from the Green & Pleasant Land.

The creators of much of our literary, journalistic and cinematic popular culture are from the upper middle class or society’s entitled set. They have moulded a myth about Britain during the Second World War that was cast from their privileged position in society. The working class are archetypical and a backdrop, used for comedy, whinging, dead bodies or examples of a Tommy who learns through battle that democracy is worth fighting for.

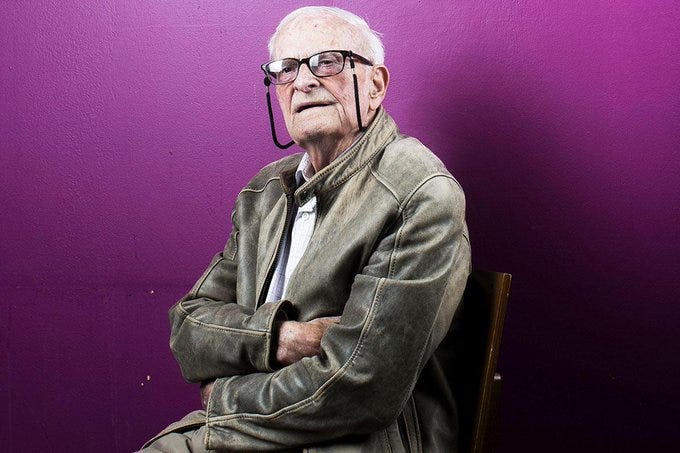

My dad, who was from the lower rungs of the working class didn't experience war like someone from the middle class. He didn't hate Britain. But he did detest the people who owned it and those that managed it for them.

My father’s experiences in the Second World War were not about being patriotic or dutiful. They were about surviving it and returning to a peacetime that included the construction of a modern Welfare State. It’s evident that the reason why our working class history during the Second World War was rewritten by popular culture is to keep us obedient in an increasingly unequal and authoritarian society governed for the benefit of its top income earners.

There is so much the poor must do to stay alive that they find shameful and undignified because capitalism exploits the many to enrich the few. Harry Leslie Smith's The Green and Pleasant is a history of one family's struggle through the hostile terrain of capitalism during the Great Depression. It's a testament to how a working-class generation born during- a period of extreme hardship fought to survive with their humanity intact during years of economic deprivation and World War.

From their struggles, the modern Welfare State was born only to be destroyed by neoliberalism over the last three decades.

What we are living now will only get worse. It will take more than a generation to change.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy and me alive is greatly appreciated. So if you can please subscribe because it literally helps pay my rent. But if you can’t it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury.

The Green & Pleasant Land:

Chapter Thirty-Two:

Eighteen months into the Second World War, the sky and foreign lands were battlegrounds soaked in the blood of my generation. I knew from the age of four when my sister Marion died that death was horrible, painful and final. There was no coming back from it- and no heaven after it. So, I was not about to surrender my life before it had even begun to a King or a country that starved me as a boy forcing me to rummage in rubbish bins for food .

Most of the other young men stationed with me at RAF St Athan were of similar mind to me. There was little enthusiasm for the war in the lower ranks because fighting for a democracy that only promised the working classes, substandard housing, no healthcare and a yearly fortnight's holiday from work at a mill, foundry or coal pit wasn't enough to sacrifice your life for. At St Athan, you heard more loyalty to someone's local football clubs than to Britain or the King.

At St Athan, I was sociable but was reluctant to form close or honest relationships. I was bookish without a formal education and that made me self-conscious. I felt I had secrets about the harshness of childhood that I needed to keep buried from others. I feared humiliation because poverty is a shaming experience even if everyone in your class has had their brush with it. Capitalism is like that it makes destitution the fault of human failings rather than about a corrupt and greedy system.

If prodded about civilian life. I made it sound as broad and humdrum as possible. I mentioned things about football pitches, pubs, dance halls, cake shops and the pretty girls I knew in the peacetime neighbourhoods of my recent past. I bull-shitted them about my family because my personal tragedies weren't their business and it was something I wanted to put behind me.

If asked about my family, I invented a narrative that made my upbringing less harsh than it actually was. If someone asked about my father, I said he was dead despite him being very much alive but desperately poor, living alone in a doss house in Bradford. Instead of talking about my real Dad, I told them my mother was remarried to Bill, a butcher. I said our family had Sunday roasts and listened to football matches on the wireless.

I wanted the RAF to be my fresh start and a chance to learn a skill that might be useful in civilian life if I survived the war. Or at least, that is what I told myself and the mates I began to chum around with when we were permitted to go to the village pub on a Saturday night for a piss-up.

Day in and day out at St Athan, my primary ambition was to become so good at Morse code that I wouldn't need to be used as cannon fodder. It was slow, repetitive, and painfully dull progress. But over the weeks, I became proficient in keyboard transmission, signal identification, speed, and message retention.

There was a purpose to this new skill I was acquiring because outside of my classroom, thousands of real messages were being transcribed, sent, and coded each day by a well-trained signals corp.

These messages detailed bombing missions, troop advancement, and endless Bomber Command casualties. They were coded lists of men lost over enemy territory or terse reports about crashed aircraft. They spoke of planes being too shot up to land safely and men dead upon impact.

In late September- I passed my wireless exam and was granted leave to return home for a few days.

On the day I returned to Halifax; it rained forlornly onto the rough, and worn working-class streets of my youth. Before I went to my mother's house, I had a beer at Halifax's Grandest Hotel, The White Swan.

Along the way from the rail station, newspaper headlines written on chalkboards in front of shops cried out about Luftwaffe air raids against Britain, the encirclement of Leningrad and the fall of Kiev. We were not winning the war, and nor was Russia, which entered it in June of that year following Hitler's invasion.

In the sparsely populated White Swan bar room- I savoured a half pint of bitter. The other men along the bar rail, business people, ignored me in my blue serge uniform as easily, as they had done when I plied a barrow for Grosvenor's Grocers and wore a worker's cap and coat.

When the bus dropped me off on Boothtown Road, I walked the rest of the way to my mum's house. I was disappointed no one was about.

I wanted her neighbours to take note that I was in the RAF blue, and they could all get stuff because I was now part of a war machine fighting for their safety.

When my mum saw me at her door; she said sarcastically.

"Look at what the cat's dragged in."

When the kettle was on for tea, my mother informed me that my sister Alberta was doing as well as expected. "Her man did a runner from the army and she's got a wee bairn on her tit."

During the early part of my training, Alberta sent me a brief note that she had given birth to a boy. I sent congratulations. But I didn't understand or want to understand the enormity of her problems. They almost overwhelmed her because Alberta had to raise a child with few resources in wartime, and a deserter for a husband that the police were looking for.

I drank my mum's strong tea in her worn and spartan parlour. My mum complained that there was no sugar for the tea or coal to ward off the dampness because of wartime rationing. As I sipped my cuppa and listened to my mother's complaints and requests that I send her more money from my pay, remorse, affection, and revulsion for her shifted in my heart like an uneven load on the back of a lorry.

I smugly thought after six months of keeping in step with the parade Sergeant I had escaped my childhood and its painful memories. I thought to myself as I looked coldly at my mother in a day I'll be gone and I won't come back even when this bloody war is done.

My homecoming with my mother was expediently interrupted when Bill arrived home.

“Let’s have a look at you. You did alright, lad. There’s no muck on you, Harry.”

I visited my sister the following morning, who now lived on Low Moor. On the bus journey to Bradford, I saw an endless display of wartime propaganda posters on advertisement boards telling civilians to be vigilant for spies and saboteurs.

Alberta's house was a one up and one down on a hilltop where the air was thick from the coal fire of weaving mills. Until that day, I had never gone to the house she moved to after marrying her husband before I joined the RAF. I hadn't even gone to her wedding in 1940 because I couldn't afford to lose a day's pay. Although my mother had gone and wasn't impressed. Upon her return she muttered to me about marrying in haste and repenting in leisure.

The man she married, Charlie, I didn't like. He had an air of violence and drink about him. As it turned out he was fine with hitting women but when it came to Germans he didn't have the stomach for fighting someone who might kill him. So, after Dunkirk- he bolted from the army but not before getting my sister pregnant and then leaving her to raise a child on her own.

I hadn't seen Alberta since my birthday six months previous. The change in her physical appearance was shocking. My sister was anaemic, underweight- almost a skeleton with skin for clothing. She had lost much of her hair from the stress of police harassment. Local coppers and military police came frequently to my sister's place of work and home harassing Alberta over her husband's disappearance, from the army.

Alberta was reluctant to talk about her life and her husband. And, I was hesitant to speak about my RAF days as I thought it insignificant.

She said.

“You men get all the bloody luck and glory. Look at you in the RAF. It’s a life of adventure, no dull days down at the mill for you.”

At the time, I did not know what she meant. I never fully understood her words until many years later. My sister was far more trapped by the bonds of earth, kith, and kin than I was as a man. Society denied her the right to a well paying profession and financial independence. There was no where for her to run and no bolt hole to hide in until the storms subsided. Even her husband's desertion from the army was considered her sin as much as Charlie’s.

When I left she said. “If you need something, just holler. I will help.”

“Ditto,” I replied, kissing her ashen coloured cheek.

Sadly, I left knowing that neither of us would call upon the other if we needed help. We both believed, wrongly that our problems were burdensome and added weight to the other’s responsibility.

The next day, I left my mum's house at six in the morning with a terse Tara and caught the train back to St Athan. On board, the carriages overflowed with joking and weary faces of soldiers, sailors, and airmen returning from leave.

For me, rent day approaches like the headlights from a truck with an unsteady load on its trailer. It leaves me stuck in the middle of the road, transfixed by it, or perhaps I am too tired to react this time and jump out of its way.

A yearly subscriptions will cover much of next month’s rent because all I need is 6 to make August’s payment. But with 5 days to go, it is getting tight.

Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

Heartfelt as always. A much needed story being shared here, as opposed to the “lifestyles of the rich and famous” one’s we are subjected to — manufacturing consent, a form of elite capture. Your father’s insight into the hardships endured by women in general and working class and poor women specifically resonate straight into current times. Thanks John.