Peter died on this day in the before times, fifteen years ago. He was my older brother, my friend and sometimes even my rival. As deaths go, Peter had a shit ending at the early age of fifty. He died literally like a fish out of water because his lungs were so diseased from pulmonary fibrosis that even an artificial respirator couldn’t give him the air he needed to breathe.

It was a bad ending for someone who drew so many short straws from life because even before his lungs began to fail, mental illness was his constant adult companion.

In his late twenties, Peter was diagnosed with schizophrenia during a time when like today, there was extreme stigma against those who suffer from a debilitating and personality altering mental illness. He lost friends, a career, independence and hope.

The only reason why Peter didn't take his life or end up derelict on the streets when first diagnosed was because of my parents unreserved loyalty and love to their son.

Mental illness didn’t stop him from living a life with many moments of wonder, joy, laughter, and love in it. But it was a massive impediment that stunted his potential and life span.

Peter, unlike most of us, was able to define the experiences that shaped his life because he was a visual artist.

In that way, he was luckier than many others with mental illness because, for most of us, life is a linear progression- childhood,

youth and adulthood. You take a job, enter into a relationship to begin the whole rinse and repeat of existence for another generation.

Schizophrenia puts a giant spoke in that normal wheel of life and it is hard to find your way back to hopefulness.

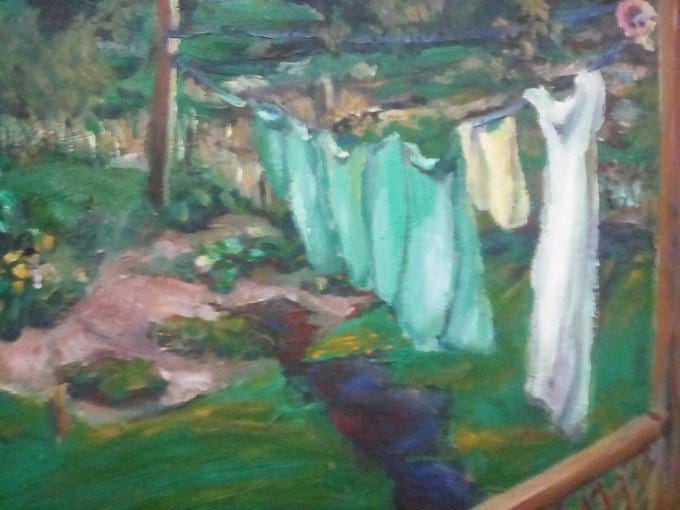

Instead with my father's encouragement, Pete used his talents as an artist to explore, define and portray his existence that included the mundane, the profound, the humorous and those moments when he was in the grip of paranoia, anxiety, or loneliness.

My parents kept Pete alive by denying themselves a life, which is the role of all caregivers in broken societies. Being Peter’s caregiver took an enormous toll on my parents because they were already in their 60s when he became severely ill. It ended all their hopes and dreams for a retirement spent in productive leisure after beginning their lives in the harsh extremes of the Great Depression and the Second World War.

.

Despite the myth neo-liberals tell today of the good old days of the 1990s, my parents had no government support to take care of Peter. What Reagan, Thatcher and Mulroney hadn't obliterated of the Welfare State in the 1980s, Clinton, Blair, Chretien and a host of Canadian premiers pounded away at what was left of it in the 1990s.

When Peter was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1991, there was nothing left but family support to keep him alive. It tapped out much of their savings, which they had squirrelled away for their rainy days.

My parents admirably performed the role of caregiver to Peter. But they paid a heavy price because caregiving shortened my mother's life. When my brother’s psychosis made him speak in tongues and turn every picture or painting in my parents’ house to face the wall because they told him to kill himself, my mother battled her own ailments like rheumatoid arthritis. It left her an invalid and required many stays in the hospital. In later life, my mother was plagued by physical infirmities because the stress of being a caregiver made her ignore her own needs. She developed shingles and then, after a series of silent heart attacks whose symptoms were ignored by her doctors, was rushed to hospital for a quadruple bypass operation. My mother survived all that before dying of cancer, which, despite causing intense physical pain, went undiagnosed until three days before she died on July 2nd, 1999.

On her deathbed, my Mum was provided with some grace to make her dying easier. She was allowed to believe her self-sacrifice produced the potential for a happy ending to Peter's life because my brother married his long-time girlfriend a month before she died.

Life is more Chekhov than Jane Austin because- although Peter, after my Mum’s death, was afforded a more independent life owing to a change in his medications, it was short-lived.

The wonder drugs that alleviated and lessened the symptoms of his schizophrenia are also believed to have encouraged his lungs to become fibrotic, killing him in the shittiest of ways when he was on the cusp of artistic recognition and still a very young man.

On Pete’s last day of life, I asked him if his mind was made up to die?

I said if it wasn't; I’d advocate for his right to change his mind with the doctors.

“You always had my back.”

Pete indicated by nodding his head he wanted me to fight for him.

I returned to our family members waiting in the ICU’s lounge. I told them Peter wanted to live, but outside of my Dad, everyone was resolved, it was his time. I felt like Henry Fonda in the movie 12 Angry Men, except I capitulated too easily. I only debated the merits of Pete living for less than five minutes. When it was decided his ventilator would be turned off, I asked how it would end for him.

“Easily,” said the doctor, “some families play music, others pray, and some do nothing .”

My Dad looked older than his eighty-six years and utterly alone in that room.

I didn’t know what to do for you, or what to say to you. I didn’t think your heart would take the death of a son so late in your life. He was furious that death had come for one of his boys rather than him- an old man. Peter dying changed both of us and for the first year after his death, my Dad tried to hasten his own. I knew for as long as my Dad lived, it was my responsibility to ensure that the remainder of his life had the same care, love, and compassion as he had given to Peter and my mother as their caregivers.

From 2009 until 2018, I helped my father through the last decade of his life the best way I knew. I helped him become an author, a speaker, and a social media personality for socialism. I did it because all the death and sadness that came to my family had to have some purposeful good evolve from it.

Something had to outlast those days of death. Or- to paraphrase Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca- their lives should add up to more than a hill of beans in this crazy world. But as this is Peter's day when he became no more. He should have the last word.

In an email to a colleague shortly before his death, Peter wrote:

"What are our stories? I am neither pessimistic nor positive. I do think things will be lost, and things will be found. We will change, and our nature will change us. We wake to our oneness, but also with a feeling that we are also part of something infinitely larger than ourselves. I would have to say the time I had with its good and its bad was a fucking blast."

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

John, your family are amazing and you are holding and sharing their spirits in a beautiful way. Stay safe my friend.