By the autumn of 1930, my family had lived rough in doss houses for two years. We had upped sticks half a dozen times, and because of it, nothing felt permanent or secure to me.

My mother doled affection out to my sister and me as if it was as hard to come by as food for our tea. It was portioned in morsels, specs of love no bigger than a scrap of chicken in a watery broth. Her love in the waning months of that year was an affection as weak as the taste made from tea leaves used over and over for a morning brew-up.

Mum didn't have the time I required to feel nurtured and safe. She had too many others calling for her attention. My infant brother Matthew for one, and Bill the cowman, who the outside world believed was her husband rather than a partner for adultery against my father.

Dad's demotion within the family was another factor that enhanced my uncertainty that the ground I stood upon was stable.

Since his pocket knife attack against Mum after learning Bill was his replacement Dad was more shadow than substance in my life. He was sunlight at 4 in the afternoon on a winter's day to our family, something that was quickly setting beneath the horizon.

Being jobless he was forced to accept my mother's affair with Bill as the only way for his children to survive the financial storm, caused by the Great Depression, which battered our family. He was shamed by his unemployment and that humiliation never let go of him. He was so debased by self-loathing; that it oozed from him and stained my human development and Alberta's.

Despite being a small boy, I knew calling my father grandad was a wicked and cruel betrayal. My opinions and reluctance to do this were not considered important to my mother because- like everything else that occurred during those harsh years- it was a means to survive and live another day.

Psychologically, being forced to deny my father to the outside world damaged me.

After that, I trusted no one. How could I? My mother taught me to lie about one of the most fundamental human bonds that a child needs to define their identity the ability to acknowledge their father in public and private.

Instead, Mum taught me as if it were instructions on how to tie my bootlaces to say to people in the doss or anywhere else. "He's my grandad."

My mother justified her command for me and my sister to deny our dad's identity as a means to prevent us from starving to death or being sent to a workhouse.

"Your father's a cripple because of his hernia- and there is no work for him. But Bill will feed us."

But it left fire marks of shame and self-loathing on the beams that held my personality together. My love for my parents from that point on contained rough grits of anger and even hatred for them.

Dysfunction in a family breeds so many conflicting and even hateful emotions for those we love. From the age of seven until my ninth decade, I have carried a deep shame and painful regret over how my dad was treated. I went along with the wicked deed and denied a parent's identity for food and lodging.

I deserted him as my mother had, his brothers and sisters had like his health had, and Britain had.

What a horrible and criminal waste it was for capitalism and our so-called British democracy to allow people like my dad to sink under waves of penury. Those lost to the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression were like sailors who had fallen overboard a ship. Their cries for help were heard, but no attempt at a rescue operation was ordered because they were considered non-essential cargo.

In 1930 everyone not wealthy or middle class was thrown overboard, especially working class children.

When I pushed the beer barrow to help pay the rent on our doss, I saw other seven-year-olds out playing whilst I was treated like a domestic farm animal by a society that only valued children from the homes of the middle classes and above.

Child labour had always been a key ingredient for profit to the upper classes in Britain's industrial economy since the invention of the steam engine. My parents began their working life at 12. So why shouldn't I start working, for my crust, at the age of seven because our working class world was in turmoil thanks to the 1929 Bank Crash.

I was too young in 1930 to put together the pieces to the puzzle of my exploitation and the poverty of my family. But I seethed with the injustice of how my life was expected to be used for brute labour without the benefit of leisure, love and comfort. That came through maturing and reading books that radicalised me as to how I and my class in the early 20th century were exploited for the benefit of the few.

But at the age of seven in 1930 in the dimming light of autumn and then winter, I knew everything being done by others to diminish my life was a malevolence no child deserved.

Everything ended that year my parents' marriage, my childhood and my relationship with my dad because he was gone from my life after the Christmas of that year. I would have hugged my dad closer that yuletide had I known he was soon to depart my life forever.

On Christmas morning, high above the flock mattress I shared with my sister- rain smudged the skylight window of the attic in the doss house. My body felt damp and cold underneath the coat I used as a blanket. Dad woke my sister and me with a greater-than-usual gentleness.

My father gave my sister and me each a penny candy wrapped in coloured paper. He served us weak, lukewarm tea, which he had made in the room my mother and Bill Moxon occupied below us. The tea was sweet from dollops of sugar. When I finished drinking it, I sucked on the penny candy whilst washing my face with a rag I dipped in a wash bowl of stale water.

My father instructed us to go and wish our mother a Happy Christmas. Which I reluctantly did because I was not looking forward to encountering Bill my mother's "pretend" husband.

Bill acted towards me as if he was there to smarten me up with stern discipline. He was always made worse by drink and I knew he'd had a stomach full on Christmas Eve. I heard his drunken carousing because his songs, swearing, yelling, rants, and jokes barged into the attic on the violent wings of his booming voice.

I knew meeting him on Christmas morning, he'd be hungover, sullen and prone to sharpness against me.

Downstairs, I found my mother making a breakfast of fried toast that I washed down with another cup of tea. She had a present for both my sister and me that the Church had provided indigent mothers so that their children wouldn't believe Father Christmas had forgotten them.

My mum had enrolled my sister and me in the diocese festive charity meal. Before lunchtime, I left the doss with my sister and walked to the parish church to hear mass and receive the church’s bounty.

The feast for the bairns of Bradford’s poorest catholic parishioners was held in a gymnasium owned by the Saint Vincent De Paul Society. There were hundreds of us and once we were let inside the complex, a nun gathered us in prayer.

I prayed that the nuns were in a forgiving mood that day. I did not want my ear pulled or my backside bruised by their love for discipline in the name of the Lord.

We sat on long bench tables and ate our Christmas meal. It consisted of stringy poultry, spuds, and pudding. The gravy was thin, and the food tasted of lost hope but we tucked into it with the ferocity of mongrel dogs chewing through the rubbish of a tipped-over bin. There was not much comfort or joy during the charity meal. We knew we were the outcasts of Bradford, and felt shame for being the children of the unemployed.

After the meal, a priest with a tubercular cough wearing a dingy Father Christmas suit arrived. We queued for our presents- an orange and a pair of clean socks.

The priest was impatient and irritable because judging by his breath he enjoyed drinking more than ministering to children. My sister whinged something sarcastic to Father Christmas and for a moment I thought he would slap my sister. But instead, he hissed something about wicked girls deserving nothing but a beating.

Walking back to the doss, Alberta held my hand and indulged my questions about what Christmas was like for the children inside the houses we passed on the way home.

At home, I found my father upstairs in the attic. Frost was on the skylight that was streaked with coal soot.

“Happy Christmas, lad, sorry there weren’t much for thee and thy sister. Next year, hey son, next year…”

In the first week of 1931, my father moved out of the doss house and out of our lives. He was gone as if he had never been in my life.

When I turned eight, I stopped asking my mum about my dad. He was alive, but I was told to think of him as dead because that was my mother's story, and she needed to tell that story to survive. Much later in my life, I understood to endure poverty; you must do unspeakable things. It turns you feral, or it makes you dead.

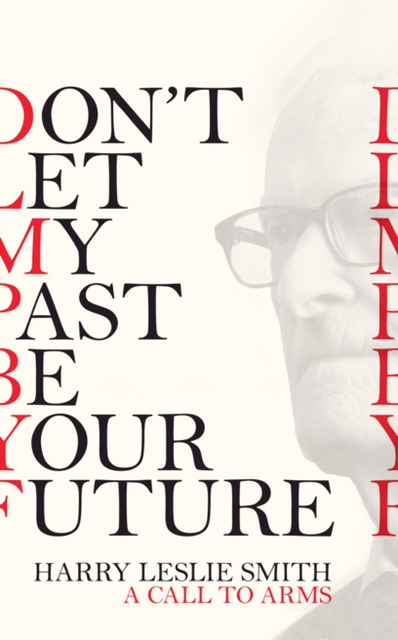

Excerpt from Harry Leslie Smith’s The Green & Pleasant Land.

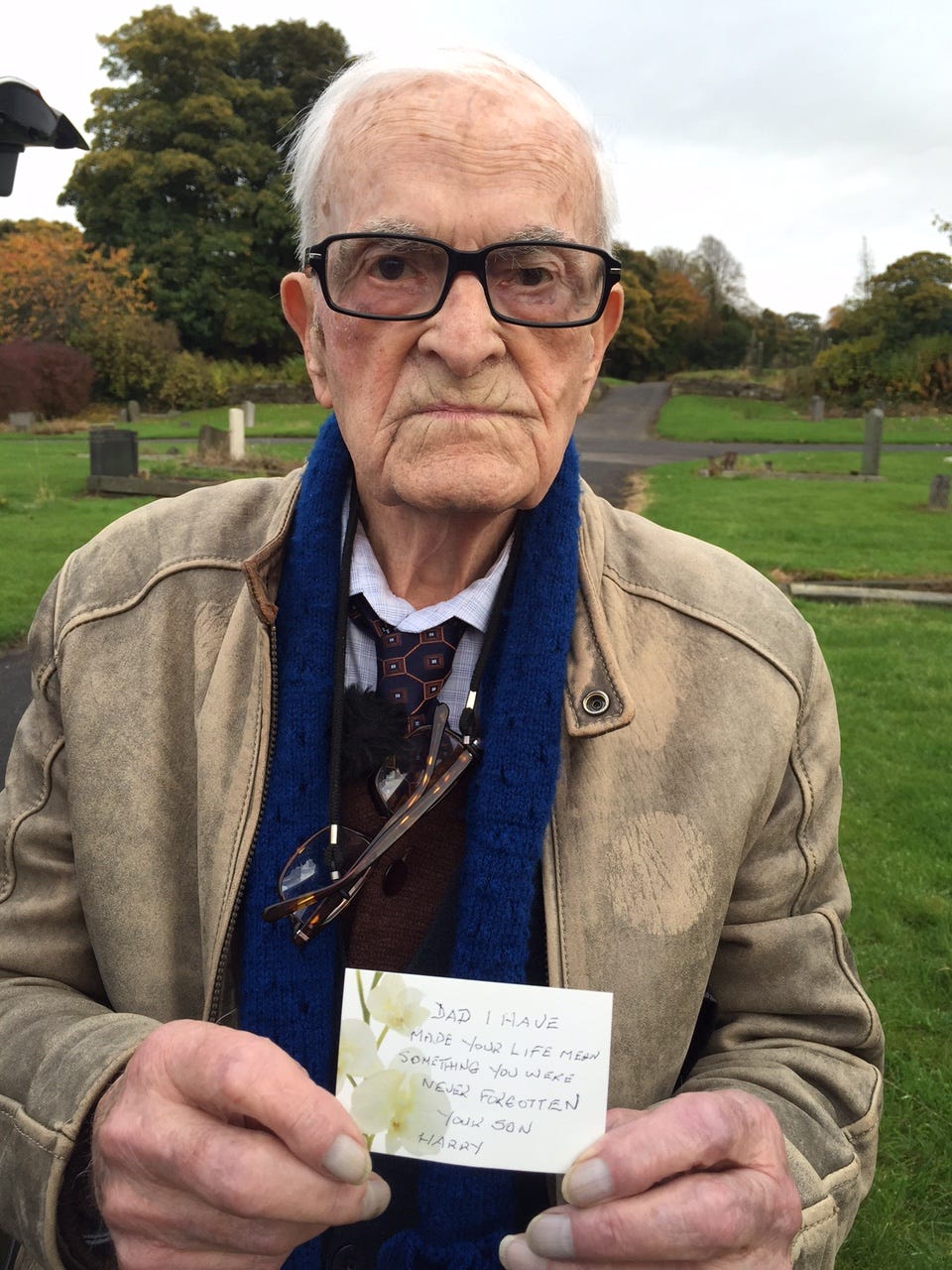

This month marks the 6th anniversary of my dad's death. It also marks the third anniversary of my Harry's Last Stand newsletter going live. During these past 36 months, I have posted over 500 essays, excerpts from Harry's final work, The Green & Pleasant Land, which was unpublished at the time of his death- as well as, excerpts from my book about him.

My newsletter has grown from a handful of subscribers to almost 3k. There are 210 paid subscribers, which I greatly appreciate because your support is one of the ways I remain housed and working on this project to preserve my dad's legacy. Despite getting cancer in 2020, and being diagnosed with Pulmonary Fibrosis in 2023, I have treated preserving the work my father and I did during the last years of his life as my greatest honour. It has been worth all the sacrifices my health has undergone and the financial struggles it has exacerbated.

According to Stripe, the payment network for Substack, my Harry's Last Stand portal will pay out around 12 thousand dollars (Canadian) for the calendar year of 2024 and around $1500 in tips.

Without it, I'd be homeless or dead. So, you have my gratitude and thanks.

Considering his past is rapidly becoming our present- Harry Leslie Smith's experience about life, before the Welfare State and how his working-class generation created a more equal society for everyone- is more important than ever.

It is coming to the end of the month, and my rent is due. So your new subscriptions, renewals and tips are more than welcome because they are a lifesaver for me.

Take care,

John

We are already headed back there. The stranglehold of neoliberalism is too tight. I hate the half of the country that voted for the return of child poverty, starvation wages and class-based mean-spiritedness, leading to fascism as the entitled kick down and never up.

Hard times. I think we are going to go back to them. Your father was a survivor.