It’s not bad news, but it felt like it when my oncologist phoned yesterday about my recent CT scans. It’s been five years since my cancer operation and radiation treatments. But I still get CT scans to check for cancer recurrence every 6 months to a year. It was on one of these scans that they detected the lung disease, which will probably kill me sooner than any return of cancer. Yet, I was still very disappointed to learn that I require further follow-up investigations. You see despite the scan looking good they aren’t sure if cancer is done with me yet. Like I said it’s not bad news. It’s, actually, very positive news because like in a game of Russian roulette, the chamber was empty again. But who knows what will happen the next time. The feeling will pass and the despondency will lift. I know others have it far worse than me. So I soldier on.

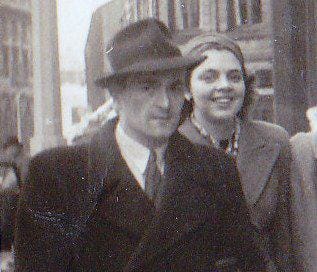

In the mean time out of sequence but still very good. Something from Harry Leslie Smith’s Green and Pleasant Land. It is 1948 and Harry has been recently demobbed from the RAF and has returned to Halifax with his German wife. As there is an acute housing shortage despite the new Labour government’s every shovel in the ground philosophy, my father was compelled to seek shelter in his mother’s tenement house.

1948 Labour’s Long March towards Socialism

When we reached the front door of my mother’s house, I hesitated. I looked down at the cheap suit the RAF had provided me and thought, You look like a bloody DP, just fresh from a refugee camp, whereas Friede looked beautiful. I feared she was almost too rare an item to be brought indoors to the world of my mother. Friede noticed my hesitation and said, “Why don’t you ring the doorbell?”

“In this neighbourhood,” I replied, “there are no doorbells.”

“Why not,” Friede asked?

I laughed. “Generally, the only regular visitors on this street are the debt collectors or the police, and they don’t need a bell to announce their visit. If you want to get someone’s attention on Boothtown Road, give the door a good thrashing.”

“Watch,” I said, then banged on the door with my open palm and yelled out that it was the milkman.

Even though she knew we were arriving that day, my mother opened her door with suspicion and restrained hostility. She sniffed the air around her to determine if I was friend or foe. At first, my mother’s appearance startled Friede. She moved closer to me- as if a giant dog had jumped at her. As I observed my mother’s looming figure before us, I thought, Bugger, the jig is up.

I shuffled nervously on my feet as my mother stood with her arms akimbo. She had aged since my last visit a year ago. In her youth, my mother was considered a beauty. But ill fortune, poverty, and too many children with different fathers had taken their toll on her looks. Nearing fifty-five, she was now only able to turn heads by the cut of her remarks rather than by her beauty pawned to poverty.

Still Mum was as domineering as ever, and she blocked our entranceway to the house with her body. Her hair was streaked with grey and combed tightly back into a bun. Her dress hung around her like a cloth thrown over an oversized dining room table. The flower pattern on her dress was as faded as her youth; both had vanished in a cold wash, scrubbed away with carbolic soap. My mum looked at me first, then over to Friede, whereupon her thick, dark eyebrows arched like Mephistopheles after his expulsion from Heaven.

My mother’s blunt expression depicted both pleasure at my arrival and mordant amusement that I needed her help. I had seen that look so many times before that I once remarked that my mother was a Yorkshire version of Janus, the god of beginnings and endings. “It all starts out with sunshine and roses and turns to shite by Tuesday with my ma.”

A layer of red lipstick on her thin lips made her first words appear to foam with blood. “Blimey, Bill, look what the cat dragged in.” She was addressing her ageing boyfriend, who had replaced my dad long ago as both irresolute breadwinner and life partner. He was wedged behind her like a cow in the back of a knackers’ van. I heard from behind, my mother and Bill, my two younger half-brothers snicker at my mother’s remark.

“Hi Mum,” I said with latent anger. “This is my wife, Friede.”

My mother’s mood changed, and she beamed with friendliness and motherly charm. In a tone reserved for creditors, my mother said to Friede, “Come in, lass. You must be plum tired after such a long journey from Manchester to humble Halifax.”

Lillian pulled Friede into the house with so much force that Bill and my brothers, who were crammed up behind her, scurried out of the way like mice avoiding a cat. My mother led Friede into the kitchen and pushed her into a seat with a strong hand.

Bill Moxon looked at me and said, “I’ll be buggered - you are the last person I expected back under this roof.”

“You can say that again, Bill,” I replied.

Friede’s face was flush from the confusion of meeting everyone at once. Friede tried to express her gratitude at meeting my mother, and instead of saying thank you reverted to German and said, “Danke.”

Lillian stopped her fussing and said - like the wolf to Red Riding Hood - “You’ve got a strange accent, Luv.”

I was about to protest when my mother blustered at me.

“Oi, lad, it’s good to see thee looking so well.”.

“You look well, too, mum,” I said with irritation.

“Ta, son, but my ruddy cheeks hide many aches. It’s been a hard war for all of us. They tell us it's done and dusted. But how do you know it’s over when we still have all this bleeding rationing? It’s been tough to make ends meet. Labour says things are getting easier for us working folk but I trust them.

Now, don’t be mucking your mother about.”

“What are you talking about, mum?” I asked. I was confused about where she was leading me in this conversation.

“Don’t be daft, lad, you know what tomorrow is. So you better ave it for me because I am not the bleeding Salvation Army.”

“What in the blazes are you talking about, mum?” I said with growing irritation.

“The coin, lad, because tomorrow is rent day, and it’s best thou not forget to honour thy mother,” she said and rubbed her thumb and forefinger together. “It is common knowledge that brass doesn’t grow on any tree near or far from Boothtown Road.”

“Christ,” I said, “you will never change, mum. You are like the bloody ferryman across the river Styx.”

“Wot?” said my mother,

“You are a bloody miser,” I said.

“Had to be,” said my mother defensively, “with you because you were all like kittens looking for milk. Somebody had to provide.”

“Didn’t stop you going out on the piss every Friday, while Alberta and I were back at home, cold and hungry.”

At this point, Bill interjected and said, “You two are like a bloody dog and cat.

In a calmer tone, I said. “I have your money, but I won’t promise how long we’ll stay.”

“It better be for a while because we did up the attic right and proper for you and your Jerry bride,” Lillian said in a belligerent tone.

“Mum,” I hollered, “for Christ's sake, don’t call her that.”

“Sorry,” my mother said, addressing Friede. “I meant no offence to thee. “We just never had a German staying under our roof before today.”

At this point, a truce was declared when my brother Matt brought out a plate of sandwiches.

“Got them fresh this morning from Grosvenor’s,” she said proudly. Matt placed them onto the table like chum being dropped into the ocean for a shark-feeding frenzy.

On the table, in its middle rested a thin, ornate, fruit bowl. It had been a gift to my mother from Friede. I had brought it to her on my last leave from Germany. My mother noticed Friede staring at the delicate bowl amidst the indelicacies of my mother’s household. With her mouth full of roast pork, my mum said. “That be war booty. My Harry scoffed it from Germany for me.”

“It was a gift,” I declared wearily. Suddenly, Bill Moxon opened a couple bottles of beer and poured a glass for everyone.

We sat around the table for another thirty minutes, eating and drinking while my family stared at Friede as if I had brought the Empress of China to kip in our attic. Finally, Bill said it was time for his bed because “they start you early at the Cat’s Eye factory down road.”

“How’s that working for you?” I asked.

“Pay’s not grand, but it’s steady, honest labour that will see me through until I am in the ground.”

My mother added, “It’s the only place that will keep him ‘cause of his bloody temper.”

“Lil,” moaned Bill but stopped before he started a row with her.

“Aye,” I said, “it is time we retired, too. It’s been a long day, and I want to get an early start in the morning to look for work.”

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith.

For the last 18 months, I've been piecing together my Dad's Green and Pleasant Land, which was unfinished at the time of his death. It covers his life from 1923 to July 1945 concluding with Labour winning the General election. The book at least in its beta form is ready and shortly its final chapter excerpt will be posted. Let me know if you want a copy as I am compiling a list.

Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other comorbidities, which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost-of-living, tariff war crisis times. So, if you can, join with a paid subscription, which is just 3.50 a month, or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it is all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

Glad to hear the scans were clear.

You're fortunate that your doctor is thorough and proactive.

Brilliant. Don't forget I'd like a copy please John. Please let me know how much and I'll send it to you. Thank you

Heather