The Green & Pleasant Land Chapters 5 & 6 Fascism is as threatening in 2024 as it was in 1933.

The 1930s should be ancient history. But after decades of neoliberalism, years of austerity, and an end to living wages for most workers, The Great Depression years feel like an analogue version of today. Fascism is as threatening in 2024 as it was in 1933.

This time, I don't think we can win the struggle against fascism because the political class is corrupt as is the corporate news media class. Outside of paying lip service to the struggles of the many those that govern us and those that report on our governance are disengaged from the economic and social struggles of ordinary citizens. It is a recipe for authoritarianism.

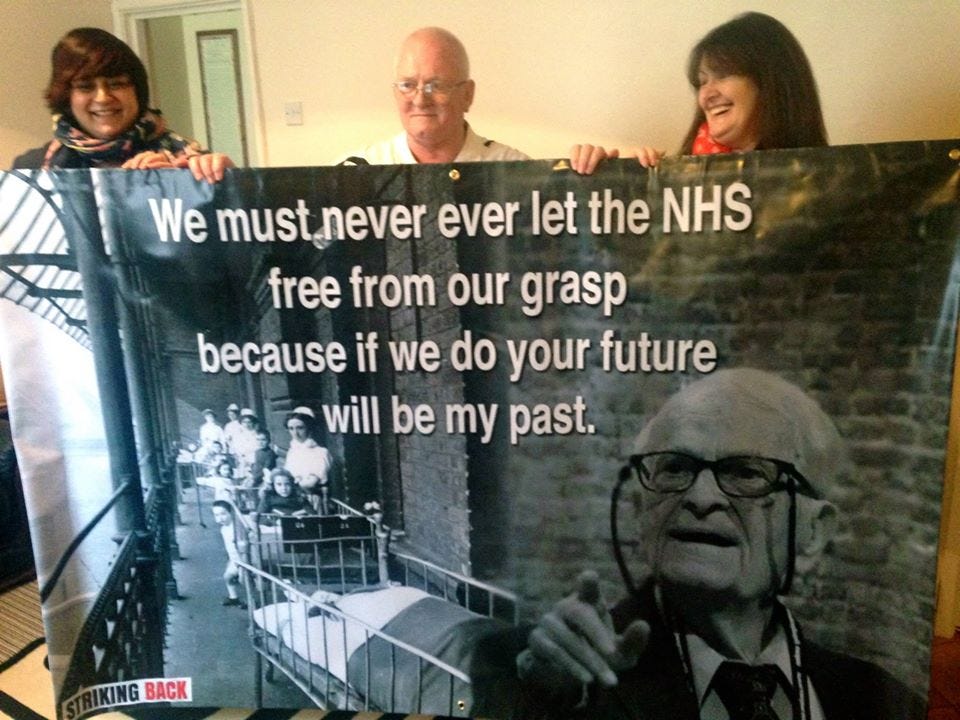

It's one of the reasons I have attempted over these last years to promote my father's working-class history on social media.

The Harry’s Last Stand project, which I worked on with my Dad, for the last 10 years of his life, was an attempt to use his life story as a template to effect change and remake a Welfare State fit for the 21st century. His unpublished history- The Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project. I have been working on it, refining it, and editing it to meet my dad’s wishes. It should be ready for a publisher sometime in June- as I want the last instalment on here to be his eyewitness account of the 1945 General Election. It will be an interesting contrast to what is offered for Britain by today’s Labour in this summer’s General Election.

Your support in keeping my dad’s legacy going, and me alive is greatly appreciated. I depend on your subscriptions to keep the lights on and me housed. So if you can, please subscribe, and if you can’t -it is all good because we are fellow travellers in penury. But always remember to share these posts far and wide.

I am navigating all the excerpts from The Green And Pleasant Land to a subfolder on my Harry's Last Stand Substack. It will be easier for readers to find the progression of the last book Harry Leslie Smith worked on before his death in November 2018. I have been editing and shaping it to how my Dad wanted it presented to his readers.

Reading a chapter here or there doesn't give the full breadth of despair and desperation endured by the working class during the Great Depression.

Below are Chapters 5 & 6 along with an audio portion of Harry speaking of those times and the present.

The Green & Pleasant Land

Chapter Five:

Humans are hardwired to keep hope alive and believe that tomorrow can be better than today. For the poor, it seldom is because when there is no social safety net; your poverty can't be outrun. It doesn't stop people from trying. Many times, Mum attempted to slip her chains of poverty. She married my father because she wanted to believe he could provide a better life for her. Instead, their marriage put both of them on a quick road to penury. Then, in 1928, after my father lost his job in the mines because of injury; she upped sticks with him and my sister and me for Bradford. She wanted to believe new beginnings were possible for those without money or work. But it was the same old...

In Bradford, like Barnsley, no one wanted to hire my father for work because he didn't look physically up to a day's manual labour owing to his age.

During our first year in the city, we subsisted on poor relief- provided by the local council. It afforded us enough for the barest of food rations- so as not to starve but not to eat nutritiously.

Being underfed created a host of physical symptoms for me and my sister, which included leg ulcers and boils that erupted on my body. These afflictions were commonplace in our neighbourhood- along with lice, rickets and TB.

In 1929, when the world's stock market crashed, neither my family nor the other residents of the slum we lived in comprehended that the greed of middle-class speculators combined with an unregulated- corrupt banking industry would wreak more havoc on our lives and society than the first world war had done.

Britain's working class thought when they elected a Labour government in May of 1929, they had bought insurance against the avariciousness of the entitled and their indifference to the living conditions of ordinary citizens. How wrong they were because it was a Labour government that sacrificed the well-being of millions of workers to the harshness of the Great Depression by implementing austerity measures that were as cruel as any Tory government before them.

The government abandoned the working class to a dole that paid an amount which guaranteed famine for the recipient. After the mines closed, the textile factories powered down, and factories shuttered as the world's economy shrank, millions of men were without incomes. and lived off of paltry benefits from the government that ensured hunger in the belly and a ravishing despair in their hearts. They were abandoned by Ramsey Macdonald's government and left to wither and rot like fruit that had fallen to the ground in autumn. My family mouldered with those millions.

At the start of 1930, fuel and food were scarce for us and everyone else without work. I still remember my mother on bleak winter mornings reheating for breakfast the porridge we consumed for supper the night before. While she dolloped it out into our bowls, I'd sing.

“Old Mother Hubbard went to the cupboard to give the poor dog a bone. But when she got there the cupboard was bare and so the poor doggie had none.”

Despite my mother securing a reduced rent in the doss we lived in, through being a harsh rent collector for its absentee landlord, we still were in arrears. Mum, for a while, charmed the landlord into patience for his money, but not for long.

So, one night before a bailiff came- we slipped from our doss house lodgings and onto unfriendly streets under cold Yorkshire skies.

My mother found us another set of rooms to live in that were more decrepit and stank of other people's sweat and misery. This new residence was in a wretched slum that possessed furtive characters who seemed to have lived their entire existence at the edge of the gutter as if they were like water rats that feared the light.

During those days in that brutal neighbourhood, we lived famished from sunup to sundown. Until one day good fortune seemed to shine down upon my family. Mum had gone out to pawn her wedding ring,- and as she walked along Manningham Lane; she spied a leather bag with a chain clasp around it. She picked it up and noticed that it had the name of a department store stencilled across it.

Curious and hungry, she proceeded to open it and discovered fifty pounds in notes and silver in the purse. It was a store’s bank purse, and an accounting clerk must have dropped it in the street- while on his way to make their daily deposit. It crossed Mum's mind to pocket the money and not say a word to anyone because fifty pounds was a King’s ransom to a family living on less than a pound a week. However, my mother’s conscience and the knowledge that she was many things but not a thief wore her down.

My mother walked over to the store whose clientele were the well-heeled residents of Bradford who had escaped the misery of the Great Depression. Inside, she spoke with the manager. He was officious and thanked her coldly for her honesty. The manager rewarded my Mum’s good turn with a tin of stale, broken biscuits.

Mum fled the store, ashamed and furious that her honesty had paid her so unjustly. Her good deed was valued by the store’s manager to be worth no more than a tin of broken biscuits in a city where children were dying from hunger.

My mother spent that night in bitter silence She was locked in a hateful glare against the tin of broken biscuits while Dad begged her to come to bed on their flock mattress that lay on the cold floor of our one-room tenancy beside the one my sister and I shared.

The following morning, Mum returned with me to the department store holding the tin of broken biscuits as if was a throttled neck. At the store, she demanded to see the manager. The obsequious attendant asked if the manager would know the reason for her visit.

“He bloody well will."

When the manager appeared, Mum slammed the tin of broken biscuits down on a counter table by the till with so much force it made other customers stop and look for what caused the noise.

“You can take these bloody things back, ”my mother shouted at the manager.

Aghast, the manager asked, “Back? But why?”

“I found fifty pounds of your money yesterday. You think a few broken biscuits are fair compensation for my kindness to your store?”

The manager arrogantly and dismissively replied.

“Yes.”

“Bollocks, my good deed is worth at least five pounds.”

“Five pounds? But that is a lot of money.”

“It’s a lot less than losing fifty pounds,” my mother replied.

“I can’t possibly…” the manager responded with haughty disgust.

“Look,” my mother said, as she pushed up close to the manager’s face. “Give me a just reward, or I am going to scream that you throw crumbs to a poor mother with two little kids to feed and a sick husband to care for.”

The manager was flustered and looked confused that someone so abysmally poor as my mother would demand more than she was given.

He didn’t know what to do. But as other customers in the store took notice of my mum’s outrage, he relented. He gave my Mum four pounds under the condition she never returned.

It was a glorious victory for my mother. For the rest of her life, Mum told anyone willing to hear the story about the day she won against the Toffs.

The money she had wrestled from the store manager for returning their deposit bag kept us fed and housed for two months. From then on, it was clear to me. It was my Mum and not my father- who would drag us to safety during the harsh economic times of the 1930s. I would, however, soon learn dragging someone to safety- does not mean they come out of a catastrophe without scars, anger, resentment, or sadness.

Chapter Six:

Over eighty years on, but I still remember 1930 as if I'd bumped into on the street yesterday. You never forget hunger or how people will betray one another for a morsel of food. 1930 was a year of famine for me, my family and working-class Britain. Hunger gnawed at the bonds that held our family together until they tore apart from a desire for self-preservation. My parent's marriage was irreparably sundered in 1930- love cannot be nourished on an empty belly.

My childhood, such as it was, concluded that year as I learned my mother did not have the emotional strength to protect me from- the harsh world- we inhabited.

During an era of economic collapse, nothing lasts, not love, loyalty, or friendship. Kindness was like ballast dropped from a faltering balloon in danger of crashing to the ground.

My mother didn’t set out to abandon my father, but The Great Depression robbed her of the ability to act nobly. By the time we came to living doss house rough, Mum knew our Dad was a dead weight that would drown us all if he was not jettisoned from our lives. In that era, my mother's only hope and mine to escape death by poverty was for her to find a man capable of earning his scratch. The problem was Mum was as bad at picking men as my uncle was at picking winning horses.

My mother crashed into the orbit of a handsome, quick-talking Irish navvy named O’Sullivan when he arrived as a lodger at our doss house. This navvy liked her too, or at least the prospect of wooing my Mum into bed. He lavished her with compliments, jokes, and flirtation.

O'Sullivan carried himself like a soldier and was sure of himself. The economic crash hadn’t stolen his sense of self-worth. Confidence was- an aphrodisiac for Mum, who had lost hers after too many midnight flits.

O’Sullivan made Mum smile and laugh, and despite my early age, I knew she liked him more than she should. Sometimes, she didn’t come back to sleep in our room at night, and there were whispers from other lodgers about the sin of fornication.

For Mum, O’Sullivan’s attentions were like a life preserver thrown to a drowning person. She reciprocated his affections and longed to be with him. She resented the time spent in my father's company and became more acerbic and cruel to him.

Nightly under the spluttering glow of our one gas light that was bolted onto a greasy wall, my Mum cursed my Dad for leading her into a life of harsh poverty. Dad did not fight back but instead apologised for his age, infirmities and the things that were not his fault. Mum was never sated by his acceptance of guilt because Dad saying sorry was not enough for her. Mum resented my father because she was the one who begged, borrowed, and stole to ensure that my sister and I had some morsel of food for our tea each night. Mum was the one who went to charity shops and pleaded for clothing for me and Alberta.

Mum was the one who obtained for me the worn corduroy trousers that were stained with the piss from its former owner at the St Vincent De Paul mission.

“I am the one who eats the shit for thee,” was Mum's response if anyone dared to question any of her decisions that affected our entire family.

Mum fell in love with O'Sullivan because it was an escape from the reality of her existence. It was a fantasy more than anything else. Yet, it had horrible consequences for everyone but O’Sullivan. My mother deluded herself into believing a new life could be at hand for her and her kids with this attractive young workman who promised her a life of plenty down south. She ignored the reality she was already married to my father, who, although disabled, was very much alive.

In the 1930s, working-class women rarely obtained a divorce because of the cost and the moral hypocrisy of that era. Facts, however, didn’t stop my mum, and she did all that she could to make herself become more than a fling to O’Sullivan.

Although she went about it most peculiarly because her Irish lover didn’t seem to my childish eyes to be a man of any faith, save for that of self-preservation and taking, damn the consequences, what he could from others.

It got into Mum’s head that if her children were the religion of her lover, it might be easier to pass us all off as a family unit. My mother was plotting ahead and reasoned that my dad could be abandoned- while she, Alberta and I would live with O’Sullivan outside of Yorkshire as a pretend family. To aid in this fiction, my mother had me and my sister converted to Catholicism whilst she a sinner, stayed far away from any confessional.

Yet it was not just lust that drove my mum to embrace the Church of Rome. Mum had heard that the catholic church in Bradford provided better food parcels than the Church of England.

I remember my first day at that catholic school and being terrified by the priests whose faces were whisky-red from too many nights of cards and cigarettes. I soon learned it was not the priests you should fear but the nuns who taught me my catechism.

Sister Christine was the nun I learned to fear more than anything else because she seemed charged by God himself to deliver his wrath against me. Sister Christine was a dour, unhappy character who took no joy in beauty or in children.

One day at school, the Sister instructed our class to draw an apple that sat on a table. Like a creeping Jesus, the Sister moved around the room on rubber-soled shoes to inspect the drawing prowess of each student as if she were a judge at an art competition. When Sister Christine came and inspected my drawing of the apple, she was not pleased. The nun said with disgust. It was sloppy, smudged an insult to her and God. Not satisfied with verbal barbs, the Sister so outraged by my drawing, struck me with a strap across my forehead. The strength and ferocity of the blow made me black out for a moment. When I came to, I wept in pain, fear, and humiliation.

When I returned home from school, my mother noticed the bruised whelp on my forehead. It outraged her that a stranger dared to physically punish a child of hers. Mum would have her retribution and went to school with me the following morning to confront Sister Christine about my beating.

“I hear you’ve been disciplining our Harry for not meeting your fancy apple approval.” Sister Christine obfuscated and claimed I had been acting out in class.

“Sister, mark my words, touch my boy again; I will beat you black and blue with my very hands.”

Upon leaving, my mother said to the nun, whose mouth was agape in surprise and fear, “Justice is mine sayeth the lord.”

*********

As my birthday gift, Dad found a few spare pennies- and took me to the Alhambra Theatre to watch a pantomime of Humpty Dumpty. He could only afford the cheapest seats, which were high up in the theatre.

While we climbed to them, he said, "Mind you don't bump your head on a nearby cloud." But I didn't care. I had never been to the theatre, and I was just thrilled to be in the company of my father. When the performance was over, I felt I'd been touched by magic. However, that feeling of exaltation didn't last long.

My joy from that afternoon matinee was quickly dissipated by witnessing my parent's marriage founder on the sharp rocks of poverty, infidelity, and mutual recriminations.

My mother's affair with Mr O'Sullivan caused extreme discord within our family. There were arguments, yelling, and hurtful things said to each other, but never any physical violence. Mum was desperate for love, for an escape from our poverty. She blamed my father for our circumstances and berated him in front of me.

After my birthday, something snapped in Mum, and she concluded enough was enough for her. She deluded herself into believing that O'Sullivan could save her and her children from the Dickensian poverty we lived in and ran away with him to start a new life. Mum believed all things in her life could be fixed if she ran off with O'Sullivan.

My mum fled south with O'Sullivan because he had friends and work available to him in St Albans. They left by train to an England she had never seen before. Mum never read the book. But maybe when the movie version of Anna Karenina came out in 1935, she watched it at the cinema and recalled her desperate escape from Bradford in March of 1930. She might have recognised her own experience of attempting to flee destiny in a third-class carriage that trundled its way to London, she, like Anna, had chosen the wrong man to live in exile with.

My family waited through the early spring for news of my mother, but none came. During that time, my dad, my sister, and I survived on handouts, begging and sometimes the pity of my mum's relations who came over to our doss house and paid the arrears on our rent or provided leftover food from their table.

Dad tried to be strong for his children, but what happened to him and us in the year 1930 beat him like a vicious drunk beat their disobedient dog. My father emotionally retreated from his children and the reality of our destitution. On occasion, I found him staring at the grimy walls of the room we lived in, with tears rolling down his face. However, most days, he escaped the world by taking long walks around the city of Bradford or by reading from his eight-volume encyclopaedia of the ancient world. In 1930, I was seven and alone outside of my ten-year-old sister's protection in the harsh environs of Great Depression Bradford.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. A yearly subscriptions will cover much of next month’s rent. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John