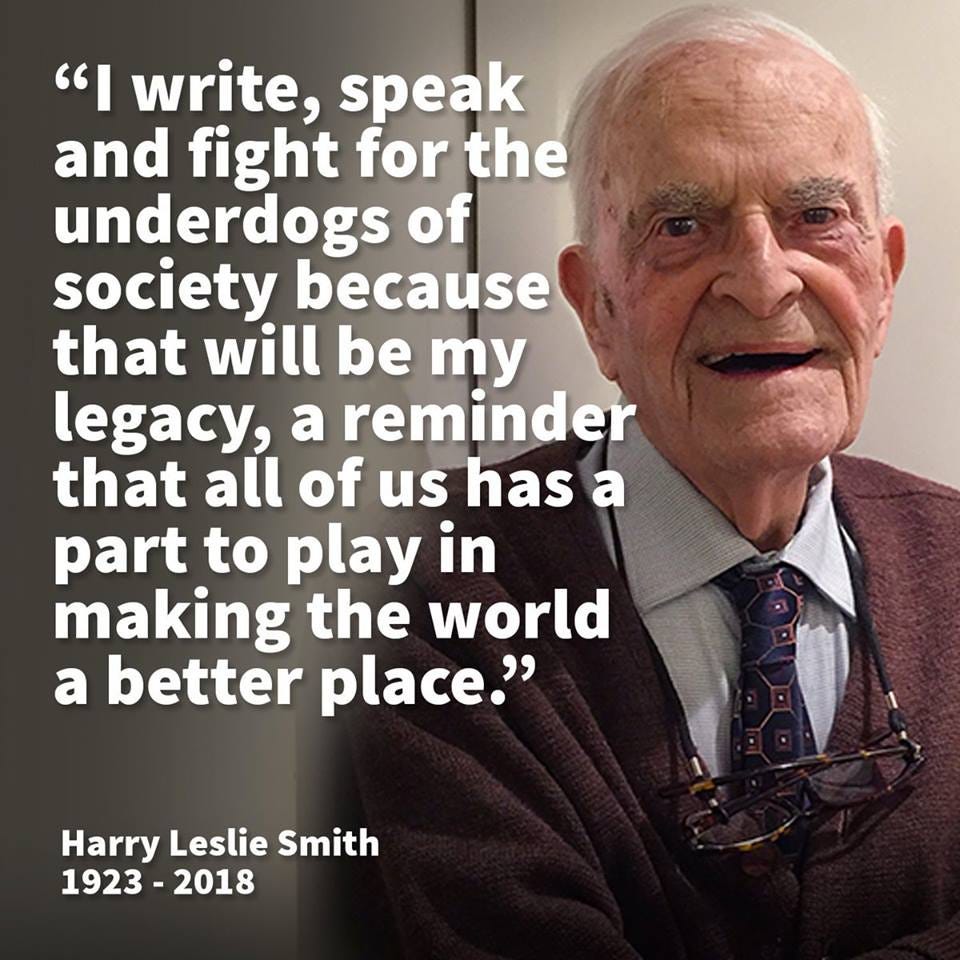

Below is Chapter 13 from Harry Leslie Smith’s unpublished The Green and Pleasant Land. It’s a history, memoir, polemic and prose poem about working-class life before the Welfare State. I hope you enjoy it.

Chapter Thirteen:

During the first week of 1931, Dad moved out of the doss house. He left quietly, without fuss or fanfare. Dad patted me on the shoulder and told me to be a good lad. And with that, my father slipped the moorings of our family and vanished from my life. My father was the one who left but it was my mother who had deserted him. If the times had been kinder, the circumstances different, Mum would have not done what she did to my father. She wasn't a cruel woman but the Great Depression hardened her like it calcified us all.

Forcing my dad to move out and exiling him from his children was a brutal punishment for the sin of becoming disabled at work and because of it unemployable. Rewriting my dad's narrative to exclude him from fatherhood, and humiliating him by changing his stature to grandfather to the outside world because it allowed my mother to take up with another man who had employment to ensure the survival of his children was also a merciless punishment. Still, it was Mum's only solution because- working-class divorce was precluded owing to its expense as well as society's sanctimony. I knew it was wrong that my dad was evicted from our lives, and denied his right to be called our dad. I protested to my mum but not strongly enough. Alberta fought harder for our dad. But she was three years older than me. So being ten, Alberta knew Dad was as good as dead to us once gone from the doss we called home. Yet even Alberta gave up the fight for him. Like us all hunger and the fear of being sent to a workhouse overcame her loyalty to him as well.

The betrayal of our father allowed my sister and me to survive childhood during the dirty 30s. But it destroyed us as a family. It was a scar on our souls that didn't heal. It made us both love and loathe our mother in youth, middle age and old age because she implicated us in the destruction of our dad. It wasn't until she was long dead that I truly understood my mother's sacrifices to keep us alive that she did not deserve my rancour over the harmed caused to me when young.

With Dad gone; Bill Moxon became the central male figure in my childhood. Moxon was a man of quick temper, explosive rages and extreme intolerance. As human beings go, Moxon and my dad were polar opposites. My dad loved poetry, history and nature. He was a socialist and a kind man who believed in trade unionism as a path to a better society.

Moxon was barely literate and no socialist. My mother's new boyfriend was an angry man and I tried to stay well clear of him. Soon after my dad left, Bill lost his position as a cowman because he got into a fight with a foreman, over some real or imagined slight. To my mother's relief, Moxon quickly found another job. He was hired as a pig handler at a nearby farm.

In the mornings, Moxon travelled across Bradford with a horse-drawn cart. He collected slops from the restaurants and pubs for the pigs to dine on. On occasion, he brought home for Alberta and me a large formless mass of discarded toffee that was intended for the pigs to eat from the Mackintosh sweets factory.

With a hammer, Alberta and I chipped away at the mound of toffee that had bits of wax paper stuck to it. Eventually, our hard work transformed the mass, into shrouds of thick brown treacle. We sucked the sweetness from it as a carnivore licks the marrow from a bone.

Not only was Bill in charge of feeding the pigs, but he was also responsible for cleaning their styes of their shit. Every day, he shovelled, washed, and scraped away the effluence of four hundred well-fed pigs. After his shift was done he rode the bus home stinking of shit. When he returned home, his stench enveloped the doss. But the other residents feared his temper. So in his company kept schtum about his foul odour.

One weekend, Bill needed me to give him a hand at the pig farm to do a "man's job," he said. Moxon was too ignorant to understand I'd been doing a man's job ever since my mum put me to work as a beer barrow boy for the off license down the road from our doss house, when I turned seven.

When we arrived at the farm, Bill explained he had come to kill a pig. I was required to assist him because the business was dodgy. But me helping him would mean Moxon would be allowed to take some of the slaughter home for our tea. I was terror-stricken. Blood-curling images danced in my head about having to slay a giant pig.

Bill had me wait in a shed while he dragged a pig from its stall over to its place of execution. In the distance, I heard a pig wailing in terror and Moxon cursing the animal's reluctance to be dragged by a rope to his appointment with death.

The shed had a tin roof, cement sides, and a stone floor. Across the back of the shed were two large steel rails. There was a hook with a rope attached to it. The hook rode the rails on a metal wheel attached to it. On the floor, there was a giant sledgehammer, which appeared to be the same height as me.

When Bill arrived at the shed, he yelled.

“I’m going to put this noose against pig’s mouth on top of teeth. Come quick, I need you to hold the rope as tight as you got. Piggy’s head has got to be high to the sky. Don’t let go of im, lad, because I am going to clout im, from behind with hammer.”

The pig struggled with every turn to break free. I was terrified that the pig would escape and attack me for threatening his life.

I stammered “I can’t do it, Bill. He’s too strong.”

“You better lad or you are our tea tonight.”

The pig cried out in fury and fear. Its back end dropped dollops of shit.

I grabbed the short rope and was now so close to the pig that I smelled its frightened breath while its giant tongue slapped back and forth against yellow threatening teeth.

“Higher, lad, higher,” Bill instructed.

I felt I could not hold on for much longer.

Finally, Bill smashed the back of the pig’s head with the sledgehammer, with an executioner’s strength, and the pig collapsed.

Bill slit the throat of the pig with a long knife blade which caused blood to explode from its jugular. I was sick to my stomach and rushed away to retch.

Moxon hoisted the pig up onto the rail trolley to let the blood run clean of the carcass. Moxon butchered the pig, and we took home a small portion of meat for a Sunday roast.

When the Sunday meal was being prepared, I didn't think of the pig, its fear and brutal death. I only thought about how I was always hungry and missed having the sensation of a full belly and the feeling of safety that brings.

As always, thank you for reading my sub stack posts because I really need your help Your subscriptions to Harry’s Last Stand keep the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith alive and me housed. The selection you just read was from my dad’s The Green and Pleasant Land. It was unfinished at the time of his death. I’ve been I've been piecing it together from all the written notes, typescript & index cards. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. Take Care, John

It’s wonderful. I am so sorry it was unfinished. I reached out to you on IG.

Why is this unpublished?