"The summer reeked of mouldy potatoes fried in cheap margarine washed down with tea made from leaves flavourless from reuse."

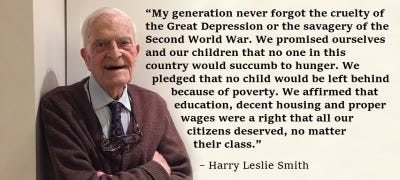

When death comes, as it will come to us all, the only thing that remains are the memories of ourselves we shared with others. The entire history of my father's life, the writings, the speeches, and the doing of ordinary things, was a political testament attesting to the need for a Welfare State where all share in a nation's prosperity and are allowed a purposeful, dignified life where one is allowed to love and be loved. Below is another instalment of Harry Leslie Smith's unpublished The Green and Pleasant Land, a history of his working-class past during the Great Depression and Second World War.

Remember to subscribe if you can, and until December 1st, there is a discount on yearly subscriptions in honour of my rent day, soon upon me. Until, tomorrow, when hopefully I will have my piece ready for you on Henry Kissinger, a man who never said no to a good genocide.

Chapter Nine: When Summer had as much Discontent as Winter.

The summer of 1930 was harsh and hungry for Britain's working class.

There was no smell of warm rain on the grass that summer. There was no taste of Dandelion and Burdock pop chilled on a cellar's stone floor to quench your thirst.

Instead, summer reeked of mouldy potatoes fried in cheap margarine washed down with tea made from leaves flavourless from reuse.

On those long sunlit days, desperation calved in Mum's consciousness. It stumbled forth into the world, wet behind the ears, but it soon matured into a concrete idea to dump my father and find a man fit enough to do a day's labour.

As for Dad, resignation to his fate germinated and grew deep roots within his soul. Dad took the role Mum had cast him, like an actor desperate to play any part for a bit of the limelight. He was now our "granddad," in public while Mum pretended to be a young widow pregnant with her dead husband's child.

It was an intricate, sad web my mother wove. Eventually, it would trap not only her desired prey but also Mum. She never escaped how she abandoned my father or the guilt it produced for being compelled to concoct that lie to ensure some sort of future for her children and herself.

Like all the seasons I lived through during my boyhood, it was my sister, Alberta, whom I looked to for companionship and mentoring. She was my best teacher on how to survive the unrelenting cruelty of poverty in the 1930s.

Alberta was wise to the streets and wise to the machinations of adults. She taught me, in winter, how to forage through restaurant bins for my tea. Now, in summer, she showed me the ropes on the best ways to harvest specked fruit that the mongers binned.

"There is no brass from the mucky-mucks for a bruised apple."

But shop owners did not take kindly to kids, who came from the barren land of doss house Bradford nicking dented and bruised fruits that were rubbish to them.

Alberta lectured me on the need for speed and quiet when we dug through refuse to pick the well-ripened fruit- that when we bit into it- dripped sweetly into our empty stomachs.

When darkness came to the day or the sun rose on it, my childhood, that summer, was shaded in hunger. But also, I felt as only a small child can, wonder at the mundane and profound sights and events occurring all around me.

In that long ago time; I learned what I have known and cherished ever since, there is magic to being alive and aware.

Our street, Chesham, ran onto Great Horton, which ended up in a large open field called Trinity. One afternoon, my sister and I heard rumours that a circus had set up their tents on the common.

Alberta and I made our way up the street, where we discovered that the clearing tents had been erected. There was a sound of hammers being struck on tent pegs while the foreman swore at workmen to be "quick about it."

Not wishing to be discovered, Alberta and I went to the opposite end of Trinity Field. There, we were camouflaged by tall grass. In the distance, I heard the sounds of exotic animals bellowing from the field. We crouched on our hind legs and strained our eyes, hoping to catch sight of this mysterious world being built around us.

The odd elephant trumpet made our mouths drop open in surprise. I was tinged with mild fear, wondering if the mighty beasts could break loose and trample us hidden in the brush. An hour had almost passed, and I grew restless. I was about to ask my sister if we could go when suddenly, Alberta began to shake my shoulder,

“Harry, Harry, come and look.”

Outside one of the tents were three beautiful, lithe Burmese women whose necks were wrapped tightly with gold bands. Near them, jugglers began to practice their act. It was a cacophony of different voices, with different accents, different attitudes, and different lives from ours in the slums of Yorkshire. Further off, I heard lions roar and in my imagination it was lion speak for "bugger off Bradford."

Everything I saw that day crouched and hidden at the edge of a circus in the long unkempt grass of the common- was enticing, forbidden, and beautifully foreign to the world as I understood it.

Remember to subscribe if you can because I'd like to finish the job I started with him and remain housed. Getting a rather bad bout of cancer at the start of the pandemic, along with a diagnosis of lung disease, altered both the trajectory of my life and the prospects available to me. If I get 6 paid yearly subscriptions by the 30th, my rent is covered for next month.

Great writing! It's comparable, in my opinion, with George Orwell's "The Road to Wigan Pier".

...’it was lion speak for bugger off Bradford.’

A great line, as was .. ‘ love does not outlast famine.’.. from yesterday.. a stack that left me speechless.

This was a fantastic read. Thanks for sharing. ✍️👏