Today, eleven years ago, my father dined at the Garrick Club with his publisher, agent, journalists and book buyers from the major bookseller chains. He whispered over to me whilst cutting into a stringy, overcooked lamb chop. "This is the fucking oddest place to launch a socialist memoir."

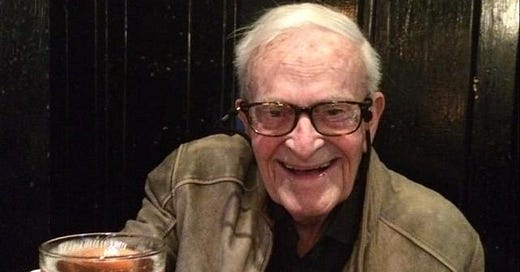

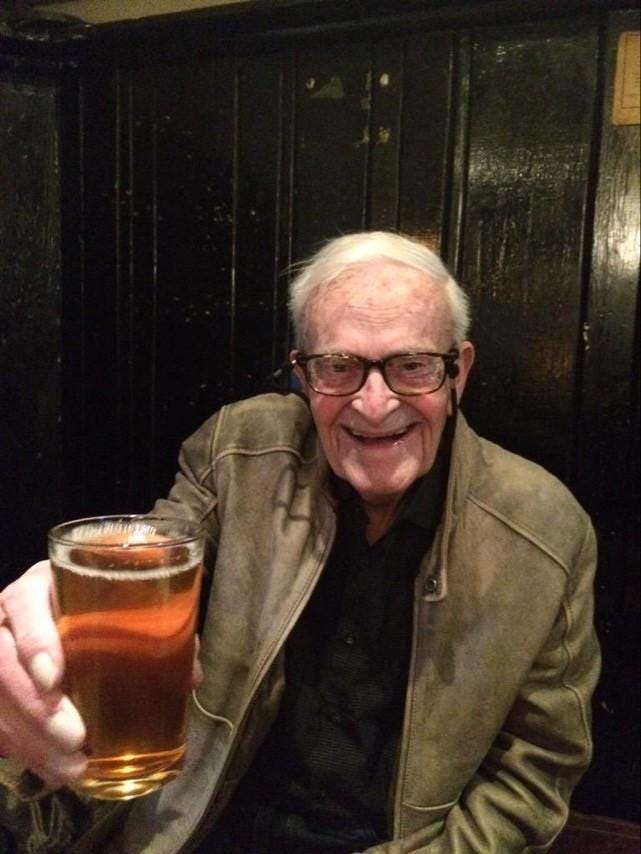

The dinner was hosted by my dad’s publisher on the eve of Harry’s Last Stand’s publication date. It was less a celebration of the book’s arrival and more designed to demonstrate to the journalists and book buying world in attendance that my father, at 91, had the stamina to sell his book. As it turned out he did. But I never doubted that because my dad had been pushing a barrow of some sort or another selling his wares since the age of 7 in 1930.

In 2014, Harry's Last Stand was a milestone because- not since the Ragged Trousered Philanthropist had a left-wing, political book, that was disguised as a memoir and written by an outsider to entitlement created such a deep impression in the public consciousness. During this week, I will provide selections from Harry’s Last Stand because it was well written and still has important things to say about life, politics and the Welfare State- despite how different the world has become since my father warned us “Not to make his past our future.”

Here is another excerpt from it. It took so much living to produce that book and the other five that it deserves a second glance even in these bite-size portions.

Like the economic catastrophe of my youth, the burden of the financial crisis was shouldered by the poor and middle classes. It caused extreme hardship to the average taxpayer through job losses and a reduction in social services. Yet the banks' wilful recklessness was never punished, nor did heads roll. No government sought to indict or prosecute those responsible for a calamity that destroyed our economy and jeopardised our social safety net through feckless greed.

I was in the Algarve when the crash of 2008 came. I didn’t hear about it right away, because the neighbourhood in the small city where I resided was populated with expats who had come to Portugal to forget their troubles. Instead, it was by chance that I discovered that Wall Street and the City were on the verge of financial collapse. I had gone to a café for my morning coffee and noticed a Guardian newspaper resting forlornly on the outdoor table opposite me. I scooped it up but I was hesitant to read it. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to disturb my retirement with news from the outside world. Near me, some local Portuguese men smoked and argued over the merits of a Benfica striker. It was a typical morning in the Algarve. The café’s table umbrellas were unfurled to shield customers from the warm sun. The street was deserted, except for the odd tourist looking for cheap cigarettes. Everything was peaceful, normal, indolent and carefree.

Even the bright blue ocean looked calm and steady, far off in the distance. I glanced at the headlines about the Lehmann Brothers’ collapse. At first, I didn’t know what to make of this financial news. Surely there must be regulations, fail-safes, and measures to rectify this? This wasn’t 1929, after all. Surely our banks had matured in the seven decades that followed that collapse of the world’s financial systems?

I put away the newspaper and decided I was too old to worry about it. I thought it was best to take a walk into the old town. I’d be damned if some banks were going to spoil my exile in the sun. You see, I had just moved to Albufeira. I had come, so to speak, to test the waters. I wanted to know if I could tolerate a cheap retirement in the sun. I was 85 and a widower. My wife Friede had died ten years earlier from cancer. But during that time I had not been alone because my middle son Peter, who suffered from schizophrenia, lived with me. He was an artist of some repute but his mental illness required him to reside where it was safe, calm and familiar, and that was with me. Fortunately, after many years of therapy, his medication improved his standard of life and he was able to marry his long-term girlfriend. He moved away and I was overjoyed at his small step towards independence. My son had suffered greatly from his affliction. So it was a great relief to me when he could now pick up the strands of his life. I was glad that he could have a go at being an ordinary husband and homeowner.

With him gone, I sold my home because I didn’t want to end up cleaning my gutters every day to keep the dementia of boredom at bay. Portugal seemed the best answer to calm my wanderlust because it was a cheap and cheerful place for an expat to avoid winter’s wrath. In summer, I returned to England and spent my days in Yorkshire. At first, life in Portugal went on as usual. I read my books, and I watched the ocean, in the morning.

In the afternoons, I drank wine in cafés near the ocean, made new friends, read books, or wrote in my journal. I thought that if this was how my life was to end, it wasn’t a bad note to go out on. But as the year progressed the financial news grew worse. In Portugal the government and the people seemed blind to the inevitable: ‘There is no problem here in the Algarve. You Brits will always come and spend your money. Look, our cranes are still building condos, flats and timeshares. You should buy into one because you can get a nice house for only 10 per cent down.’ On New Year’s Eve, the coastline was lit up by a fireworks display which cost over half a million euros that neither the regional or national government could afford. As I watched the festivities from my apartment balcony, I thought it looked more like an opulent distress flare rather than a celebration. By February 2009 the good times were over for Portugal and most of the world. Coastal towns that had survived invasion, plague, wars, fascism and communism were now deserted of the commodity they needed most – tourists. Restaurants in the city where I lived were empty, especially ones, near the beach.

Waifs with menus in hand desperately tried to press gang me and the few foreigners still left in the town to enjoy a full English breakfast for six euros. In winter, between school holidays, there were few takers, and it seemed that even the stray cats had moved out of Albufeira in search of greener pastures. As fiscal markets dried up, the Telegraph portended another Great Depression for Britain if Brown remained Prime Minister. People started talking about their ruined pension pots, and their fear of redundancy.

The only reason I didn’t was because I was struck by a personal tragedy that hit me with a ferocity that I had not known since boyhood. My middle son, Peter, who had so stoically borne his mental illness, was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). It is incurable and in quick time it turned his lungs into cement. I returned home to care for him. Within six months, he was in hospital attached to a breathing apparatus that pumped air into his foetid lungs through a hose that had been cut into his throat.

My boy, who had just turned 50, told the doctors he could take no more. His death approached like it had done for my sister in 1926 and my wife in 1999; it came like a thug in the night to torture him. He didn’t have an easy life, nor did his end provide him the tender mercy of an easy death. Instead, my son had to beg wordlessly to be no more, because the disease had stolen his voice. When he died, grief came to sit and brood in my heart. I was spent with sorrow. After Peter was cremated, I returned to Portugal and hoped that I would soon join my wife and son in death. Of course, I didn’t, because life never works out as you want, even when all you want- is to leave it.

For the last 18 months, I've pieced together my Dad's Green and Pleasant Land, which was unfinished at the time of his death. It's done apart for some minor adjustments that are required. It covers his life from 1923 to July 1945 concluding with Labour winning the General election.

Like my Dad's 5 other books written during those last years of life, The Green and Pleasant Land is an exploration of his generation during the eras before and after the creation of the Welfare State.

Your support keeps me housed and allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are crucial to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other comorbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost-of-living crisis times. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it is all good too because we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

I am glad you’re still soldiering on despite everything John, you really inspire me and I just wanted to say so.

Your Father was a very eloquent writer, I hope schools use his work to teach the realities of social history, and how it repeats itself.