The World hasn’t been this dangerous to live in since 1940. Our times may prove to be a more deadly than the death count of World War One & Two combined. Welcome to the age of dictatorship.

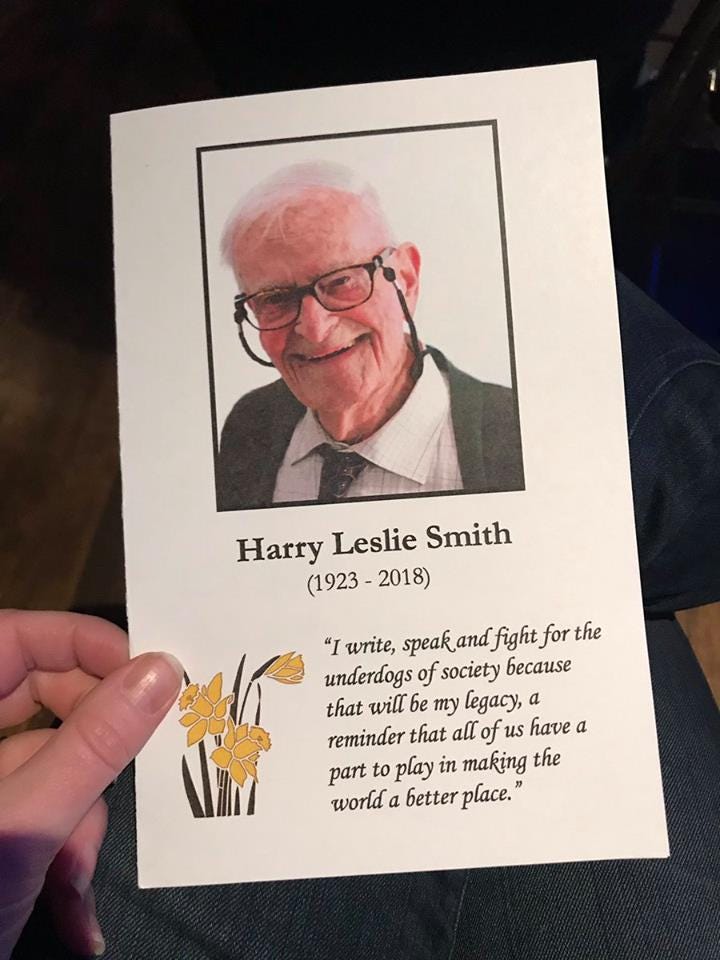

Before my father died in 2018, he spent the previous decade using the history of his life and working-class contemporaries as a political canvas to paint the dangers of unfettered capitalism for humanity and democracy. He correctly predicted that without a return to socialist politics- fascism and wealth inequality would destroy not just our society but civilisation itself.

His unfinished history- The Green & Pleasant Land is a part of that project, along with the 5 other books written during those last years of his life.

For the last year, I have been refining and editing The Green And Pleasant Land to meet my dad’s wishes. Below are more chapter excerpts from it. It is almost done and baring sickness or homelessness will be completed by his 102nd birthday on February 25th.

Chapter Thirty-Three

In the autumn of 1942, my unit was transferred from St Athan's to White Waltham. The RAF base was outside Maidenhead on an airfield that before the war was a private runway for millionaires who owned aeroplanes during The Great Depression. When I arrived there it was used as a marshalling hub for lend-lease aircraft from the USA. Day or night, a drone of arriving or departing bombers and fighters disturbed the base's bucolic surroundings.

At White Waltham, our unit numbers were bolstered with new men from the South. They came from the lower middle classes and didn't mix well with us from the working-class world of the north. The lads from the South displayed a sarcastic contemptuousness towards our accents and hometowns. It was all the product of Britain's caste system that divided humanity by their wealth and their utility to maintain an Empire built to exploit humanity for the benefit of a few entitled families. Those who were only a monetary rung above workers were conditioned to believe they were more exceptional than those beneath them. But they were also taught to understand that they were less important and honourable than those higher up on the rung of prosperity.

I didn't think much of the lads from the South- and they felt the same about me. But one man who kipped in our hut from the South did stand out, Clementine. He was the son of a lower-middle-class Oxford grocer. Clementine was considered reckless by the top brass, who refused his request for pilot training. He didn't get on well with the shop keeper sons from the South because Clementine had an air of nonconformity about him. He wasn't a socialist but he wasn't a capitalist. For that matter he wasn't for the status quo either. Clementine was an eccentric who latched on to me and Robbie, because he shared a nearby cot to ours in our sleeping quarters.

At White Waltham, my unit was marched from sun up to sound down through fields, across pasture land and down country lanes until our bodies were numb from exhaustion, by a sergeant major named Meade, who was a proper bastard.

On one march Mead stopped us midway. He shouted for us to take a good look around at the countryside.

"Paint a picture of England inside your tiny skulls because soon you will say goodbye to her. It's war in the desert for you lot. Soon, very soon, sunshines, you are going to be neck-deep in the shit-fighting Jerry. Tomorrow, you will be transferred to another drill instructor to prepare you for desert warfare."

When our marching ended that day, and it was the hour before lights out, the men in my hut expressed dismay over the news that we were bound for the desert.

Outside of a few jokes, the notion of being posted to the battlegrounds of North Africa was a dismal prospect for us. We knew what was happening in the Desert War from the newsreels we were forced to watch to bolster our patriotism and fighting spirit.

Britain was still very much on the defensive in North Africa, and it wasn't good for ordinary troops in that theatre of combat. To be sent into the desert war ensured that the King was getting his shillings worth on our lives because casualties were high and battle conditions terrible.

The following morning, Sergeant Green took over command of our unit.

At first, I thought Sergeant Green would be as brutal and heartless as Mead.

But his rough exterior was a pantomime because after several days of marching with him. He broke routine- and halted our unit in front of a cake shop.

"Right lads, time for a brew up. If you want to buy a bun or cake, go inside the shop and get it from the lady."

We then walked to a meadow with our cakes and brewed our tea. It seemed more of a picnic than a march, and some in the unit became boisterous.

"Steady on," the sergeant major reprimanded. "Keep your voices down. Gather round, and let me give you the lesson for today's sermon. I don't much care for walking. I don't much care for marching, and I don't much care for trouble. If anyone tries to grass me out and spoil our afternoon holidays, I will crucify the bastard and have their balls thrown to the camp dogs to eat."

He paused to let us digest his words and then continued.

"The most important rule in marching is always to keep the fucking load light."

He opened his kit bag to show us it was full of straw.

"My kit is like our leaders- filled with bloody straw. If you want to carry the weight of England on your back, so be it. If you want to get through these days lugging the least amount of shite. Straw is not only good for cows and horses. It's good for us because it's as light as a fucking feather."

Green allowed us to visit Maidenhead when we weren't on duty. Maiden Head was different to the villages and cities, I knew in the north because there were no slums and beggars in the streets. On the surface, it was pretty and looked as delicate as porcelain. But the shopkeepers and townsfolk adhered to Britain's class system with the rigidity of a Presbyterian honouring the sabbath. The people of Maidenhead were as sharp and rusting as barbed wire to working class northerners.

Yet, I didn't back down from their snobbery or remove my cap to their sense of entitlement. When they were curt to me at a pub, I returned their snideness with sarcasm. The war was changing British society, and I felt empowered by my uniform to be bolder than brass.

At a pub in Maidenhead, I felt confident enough to chat up a barmaid despite the derision from the mates out with me. Foolishly, I took her on a date to go punting on the River, as if I was a privileged boy from the South. Elocution classes may have taught me to soften my vowels. It did not instruct me on how to steer and chart a course in a flat-bottom boat with a pole employed as a propellant.

I ended up tipping the punt and we both ended up in the river thrashing about like two cats in a bathtub. On the river banks, a fellow airman stationed at our base observed my predicament with much amusement. After initial laughter, he came to the water’s edge and helped pull me and my companion out of the river.

My date ascended the river bank and screamed about how I ruined her dress before stomping off. The Air Force compatriot who helped us was bent over from laughter over my predicament.

“It’s not bloody funny. I had to rent that punt, look at my uniform, it’s buggered. I’ll be up on charges if an officer sees me like this.”

“Never you mind,” he said, “I’ll help get you cleaned up and back to camp without a hitch.”

The airman helped me out and on our way back to camp, he introduced himself.

“Jack Williams. My mates call me Taffy because I’m from Wales.”

Taffy was situated two billets away from mine. On the long walk back to camp, we became fast friends. He was the most open and honest person I had met. He spoke of Wales and his life before the war, near the docklands of Cardiff. Taffy spoke of his family, who had been dock workers for generations. Even though Taffy, like me, came from a callous environment, he had a wonderful appreciation for poetry both modern and ancient.

Around the time I met Jack, our unit began to learn its role in the desert war. We were to join a mobile front-line signals regiment and make former Luftwaffe airfields--recently captured by the army--operational for the RAF.

It was beyond my pay grade to understand why; if my unit was destined for the desert, I had to learn how to forge across a river with a rope strung overhead.

But in the downpours of autumn rain, we were marched to a river bank and told to cross it with a rope strung taunt above the water.

I wrapped my foot around the suspended rope to become like a marmoset gliding on a jungle vine. I shimmied slowly across the river whilst a Sergeant yelled from the opposite bank.

"Get a move on Tarzan or Fritz will shoot you dead."

On other days, we trained at target practice with Lee Enfield rifles, followed up with bayonet drills.

I charged at straw men tied to wooden planks that we had been told had raped our women folk.

Clementine displayed a homicidal delight in bayonet practice. He destroyed and disembowelled his straw man Nazi as if it were the real thing. Initially, I didn't realise it because I was too busy worrying about keeping myself alive. Clementine's character had a violent psychopathic streak to it that as the war progressed became more acute. He had a lust to hurt things that were weaker than him.

Soon after, hand-to-hand combat training, my unit was taught how to toss live grenades into trenches where we were to pretend the enemy was waiting to kill us.

It was an easy task. We stood in a safe zone barricaded with sandbags. An NCO expert in munitions ordered me to stand above the parapet, pull the pin, and hurl the grenade forward into a ditch. Once thrown, I crouched behind the sandbags and waited for the explosion.

On my first attempt, I was a natural at it. The lad who followed me was not as lucky.

He hit his mark. But the grenade failed to explode in the trench where it lay. Nothing would have happened had the man just stayed put. He didn't. He left the safety of our sandbagged enclosure to investigate why his handiwork had not exploded as it should have.

The Sergeant yelled at the soldier.

"Get the fuck back, here."

But the lad ignored the command to return.

The soldier jumped into the trench where his unexploded hand grenade sat. Suddenly, there was an explosion and then- screams like when I killed the pig with Bill as a boy came from the trench.

The soldier lost an eye and much of his face without ever engaging the enemy.

For weeks we forged inconsequential rivers, bayoneted straw men and tossed hand grenades, until one morning on parade a slow-moving Leyland lorry, built in 1917, pulled up beside us with steam brewing out of its bonnet.

An NCO hopped from the lorry's cab and bellowed; we had 72 hours to learn to drive the beast behind him.

I hadn't even learned how to use a telephone because my family was so poor, and now I was expected to master that contraption in three days.

The NCO gave me vague information about how to use the clutch, accelerator and brake.

The driving column was an enormous wheel, and the lorry had no suspension. Once, the beast started and lurched forward, it felt like I was Steamboat Willie from the Buster Keaton film.

The Leyland bounced from one side of the road to the other as if it were a drunk lurching home after last orders from the pub.

I knew my time at White Waltham was almost over because Sergeant Green said to us, following our training, that there was no Christmas leave because we were bound for Egypt.

Thanks for reading and supporting my Substack. Your support keeps me housed and also allows me to preserve the legacy of Harry Leslie Smith. Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription or a gift subscription. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John.