Depending on when you read this post, it will be either the night before or it will be the day of Donald Trump's Presidential inauguration. The American republic is now fascist. Democracy isn't coming back to that country or the vassal states who serve it without a violent clash between citizens and the powers that be.

I don't know when this uprising or revolution will happen. But it will happen because the human spirit has an unquenchable thirst for freedom. Our species is hardwired to seek enlightenment and strive towards liberty.

The Green and Pleasant Land, the book my dad worked on until his death, is about another generation's struggle towards self-awareness, emancipation and constructing societies that benefit everyone not just the entitled.

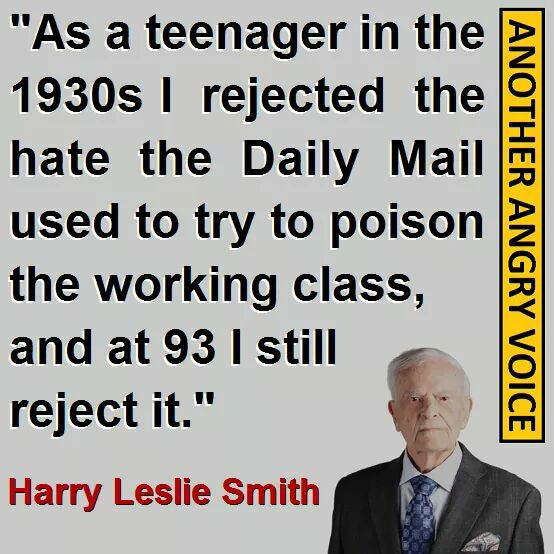

Below is another excerpt from the book. This section is about Harry Leslie Smith's induction into the RAF during a time when we fought fascism rather than today when we elect fascists to govern us.

Chapter Twenty-Two:

I stood during the journey to Padgate because the train was overbooked. Sheets of winter rain fell against the window of my third-class rail carriage.

The other passengers were mostly like me- young men on their way towards being square bashed for King and Country. There was a fug of boyish excitement within the carriage that blended into the collective smell of damp, sweat, tobacco and beer emanating from our bodies.

The further the train travelled from Halifax, across the January bleak Yorkshire and then Lancashire landscape, the more I felt emancipated from my past and the humdrumness of my peacetime existence.

However, the euphoria of change was tempered with a dark thought that becoming a participant in this war might include a letter sent to my mother telling her I had died for King and Country.

My metamorphosis into a soldier excited and terrified me in equal measures. I couldn't shake the memories I had from boyhood of World War One veterans encountered during my family's doss house years. They emerged to warn me of what might lay ahead for me and my generation. I wondered if we were going to be abandoned like the Tommies of the Great War.

I wanted to believe this time politics was on the side of workers because the government in this war was a coalition where the Labour Party controlled the domestic agenda. Attlee wouldn't betray us like Ramsey Macdonald did, I told myself.

But it was difficult to ignore my memories from 1930 when my family lived cheek-by-jowl with shell-shocked Tommies in the grimiest parts of Bradford.

At Padgate Rail Station, I followed other bleary-eyed teenagers along a road that led us to our RAF base for induction.

Inside the base, I was greeted by a warrant officer who barked.

“Have your enlistment papers ready,” Stand in a neat single file. No talking,”

In small groups, we proceeded into a prefabricated building, where there was a clatter of noise from typewriters and ringing telephones. My papers were assessed by a clerk.

“When you volunteered, you indicated you wanted to be a wireless operator. Is that what you still want to do?”

I thought for a moment and agreed it was my preferred choice. The notion of becoming a wireless operator seemed to be a cutting-edge technology.

The clerk signed my enlistment paper with a thick fountain pen and dispatched me to another section of the building where a medical doctor ordered me to strip.

I was prodded from all directions. My pulse and blood pressure were taken. I was measured and weighed like livestock. Finally, I was inoculated against diseases with injections that made the muscles in my right arm ache.

It was a strange sensation to be looked at by a doctor because up until joining the RAF, I had never been examined by one, owing to its expense.

Pushed out of the medical exam room, I tumbled down a hallway marked with arrows which pointed me towards the next station which transformed me from civilian to soldier. It was the barbershop. A man with clippers made quick work of my hair with a short, back, and sides cut.

From there, a sergeant spat orders at me to be on the double and get kitted out.

I went to another room where a clerk measured me for my uniform. Afterwards, the clerk went from piles of shirts to heaps of trousers, coats, and boots, and then neatly presented them to me.

I signed that I had accepted: one shirt, one pair of trousers, one belt, one overcoat, boots, a hairbrush, a boot brush, a cap and one kit bag. I agreed; it was my responsibility to keep, in good order, the clothing and accoutrements given to me by the King. Loss or malicious damage to this uniform was a breach of regulations which would result in forfeiture of one’s pay.

I was also given my service number, which I was to memorize. Upon request, it was to be repeated, immediately: “Smith, LAC 1777….”

From now on, the numbers tumbled out of me, as if they had been given to me at the baptismal font.

I was presented with my paybook. It recorded the weekly stipend awarded me for service whilst employed by the nation. I stammered a very civilian, “Ta.” The clerk ignored me, and he wanted to get on with the next fitting for a chap waiting patiently behind me.

I was sent to another room to strip from my civilian clothes, and then I put on my RAF blue serge uniform. I was transformed from grocer's assistant to participant, in a war against Hitler.

From the moment, I wore my rough, woollen RAF kit, my fate became the property of the British state.

When I left the building, I didn't know what to do next. I turned in all directions. I swung round to all degrees of the compass wondering where was I to go? I was not alone in my disorientation because other newly uniformed teenagers performed the same movements as me.

My disorientation ended when a sergeant charged at us bellowing.

“Get a move on, you lazy lot, on the double and follow me.”

We were led to a pile of dry straw heaped up underneath a raised tarpaulin- to keep it safe from the rain.

There, we each grabbed an empty palliasse and stuffed them with straw, as this was our mattress during our time at Padgate.

Once done, we were marched to our sleeping quarters- a Nissan Hut.

Inside, I hastily found a cot with thin wire springs and dropped my paillasse down on it.

Another recruit took possession of the cot beside mine and introduced himself.

His name was Robbie, and he was from Wigan.

He was missing many of his teeth from poor nutrition, poverty and street brawling. Later, I learnt his Great Depression was like mine, a harsh ordeal.

The sergeant returned and told us to stand at attention in front of our beds. The sergeant passed across the room like an ominous battle cruiser until he was in a whispered breath of me. For a few intimating seconds, the sergeant loomed silently near and then- ordered me, and Robbie to fetch coal to heat our hut, which had two stoves at each end.

On the way to the coal shed, Robbie confided.

“I’ll be buggered if the RAF is going to get me killed. I’m getting out of this war in one piece.”

“How?”

“Never fucking volunteer for anything. The best thing,” he said, “is to melt into the scenery. Don’t give the buggers a chance to remember you.”

“Mate, I don’t think we’ve been that successful if, on our first day, we’ve already been volunteered to haul coal.”

Robbie re-joined.

“Stay to the back of the room, Smith. Stay so far back that no one remembers you.”

We returned to the hut with the coal and received cheers from the other recruits. Later, the sergeant returned for us, and we were marched to eat our first meal courtesy of the RAF.

After eating, we were herded back to our sleeping quarters, where the sergeant hammered at us about the next day's bone-breaking itinerary.

“You love birds,” he barked, “get your shut-eye because before the sun sticks her head up and out of her arse, you'll be on the parade ground.

The sergeant doused the lights on his way out.

My first day in the RAF was over. Around me, twenty-five lads fell into a sleep that was punctuated with farts, snores and somnolent babble from dreams.

Far away in the Philippines, the Death March of Batan began for American POWs. At home, there were air raids over London and Liverpool by the Luftwaffe. And in Europe, the Nazi War machine controlled the continent except for parts of Russia that were still in the hands of the Soviets.

However, at Padgate, the hut I slept in was comfortable and warm because there was an abundance of coal burning in the two stoves. It was certainly much more snug to sleep in than my bedroom attic on Boothtown Road.

On that first night as a member of the RAF, my stomach was full from the evening meal, and my sleeping kit was clean. For now, being in the RAF seemed better than the civilian life I led in the doss houses of Bradford.

Your subscriptions are so important to my personal survival because like so many others who struggle to keep afloat, my survival is a precarious daily undertaking. The fight to keep going was made worse- thanks to getting cancer along with lung disease and other co- morbidities which makes life more difficult to combat in these cost of living crisis times. So if you can join with a paid subscription which is just 3.50 a month or a yearly subscription, gift subscription or tip. I promise the content is good, relevant and thoughtful. But if you can’t it is all good too because I appreciate we are in the same boat. Take Care, John

Americans didn't elect a Fascist. In fact, we rejected the Fascist Kamala Harris in favor of the Narcissist Donald Trump, and he already issued an executive order banning Federal censorship of American social media.

Trump's not a Fascist. He's Trump. There really is a big difference.